The First Annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize was made possible by the generous support of Southern California Gas Company.

What inspired Peter Lovenheim to get to know his neighbors was a shocking killing that took place on Lovenheim’s street in a suburb of Rochester, New York. A neighbor had killed his wife and then himself. Lovenheim had seen the couple occasionally but never gotten to know them personally. Upon reflection, he realized that almost everyone on his block was a stranger. Who were these people sharing his street?

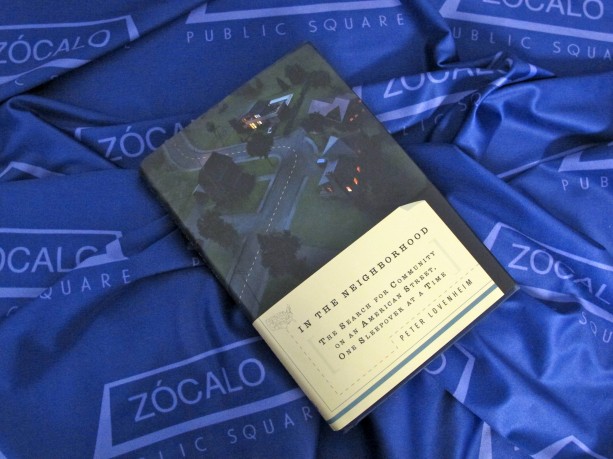

Eventually, Lovenheim knocked on every door and asked, politely, to stay over for a night. The product of this effort is In the Neighborhood: The Search for Community on an American Street, One Sleepover at a Time, this year’s winner of the Zócalo Book Prize, selected by our judges. Lovenheim’s book is a subtle and elegantly written exploration of how to create community in a fragmented age. “As Faulkner said, you only have to know the little postage stamp of the world that you’re standing on, and Lovenheim’s postage stamp is one street in one old neighborhood in Rochester,” writes one of our judges.

In the Neighborhood paints haunting portraits of the different lives unfolding on a city street and ties them into questions about the fraying of America’s social fabric over the past several decades.

On Friday, April 8, 2011 Lovenheim will visit Zócalo to receive his prize and deliver a lecture: “What is a Good Neighbor?” In addition, the winners of our High School Essay Contest will receive their scholarships. The award ceremony, sponsored by Southern California Gas Company, will take place at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Grand Avenue. Admission is free. For more event details and to RSVP, please click here.

Zócalo recently spoke to Lovenheim about his work:

Q. You conclude your book by encouraging us to knock on our neighbors’ doors. What good is that going to do?

A. It does a lot of good, both on a personal level and societal level. Looking at the big picture, I think neighborhoods were meant to be a fundamental building block of a healthy civil society. When we live as strangers to each other, we lose something in terms of personal safety, convenience, and enrichment, but we also lose the opportunity improve the social fabric of a healthy community.

Q. If the benefits of getting to know one another are so great, why don’t we do it?

A. I think there are a lot of reasons for that, but one thing that surprised me is that there’s just no social stigma attached anymore to not knowing the people next door. We can live side-by-side, driveway-to-driveway, for decades and not know the neighbors. Many factors contribute to the situation. The rise of two-career couples means that there are fewer people at home during the day. We also spend more time in front of the television, more time on the Internet.

Even the built environment has changed. In suburbia, over the last generation, lot sizes and house sizes have almost doubled on average, so we’re physically further away from each other. There was a time when you if you put a fence up in your back yard it was considered a slightly hostile act. But today you can find new housing that comes with fences already built.

On top of that there’s the whole “stranger danger” thing. I teach writing at the college level, and I have some students who are 18 and 19 years old who have spent their whole lives learning about stranger danger.

Q. Do you think neighborhoods are less cohesive than they were when you were a kid?

A. The studies show that they are. They show that on average most of us have about half as many meaningful contacts with neighbors as people did, say, 50 years ago. And that’s not just in suburbia; it includes urban neighborhoods, as well, such as high-rise apartment buildings in major cities.

Q. Do you feel the people in your neighborhood were actually brought further together by your book?

A. Well, certainly with the neighbors I got to know at a meaningful level through writing the book, subsequently they have also gotten to know each other. Since the book’s been published, we’ve all gotten together, and they’ve read about each other. So they know each other in a way they didn’t before. I’m also glad to say we’ve had more efforts to bring people together within the neighborhood in the last year or so. Whether that’s because of the book or not is hard to say, because it’s hard to know how many ripples it spread out.

Q. How does someone who doesn’t have a book project as an excuse go about approaching neighbors?

A. I think you just do it the same way. One of the things I learned from writing this book is that for the most part, most of us want the same things. The desire and need to connect is universal. Even the people whom I approached who weren’t interested in participating in the book said they wished they felt more connected. Now, some people are more outgoing than others, and some have more time than others. But I think it’s fair to assume, until you find out otherwise, that your neighbors are interested in connecting. The good news is you don’t have to sleep over at their houses. Just make the approach. I’m confident that most of them will be receptive.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s, Amazon

Send A Letter To the Editors