The Second Annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize was made possible by the generous support of Southern California Gas Company and the Shepard Broad Foundation.

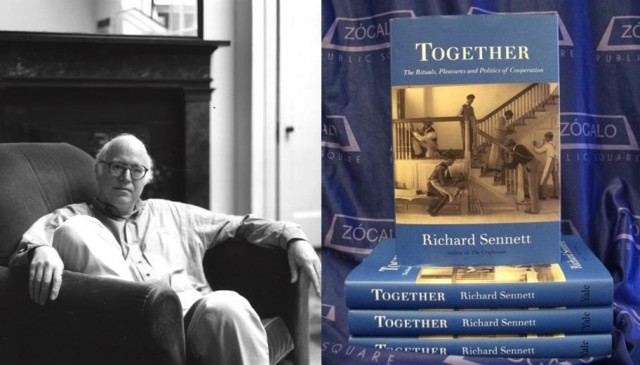

Richard Sennett’s Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation is the winner of the second annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize, presented to the author of the work of nonfiction that most effectively deepens our understanding of community. Why community? It’s not simply because we think it’s in danger, or because we’re in the business of bringing people together. It’s because we need to start thinking about community as more than the Facebook groups we belong to and the towns we grew up in. Exploring community means exploring translation and marriage, technology and collaboration. It means looking, as Sennett does, at how we can get better at living with one another.

Sennett first experienced complex cooperation when he was a young musician studying with legends like the conductor Pierre Monteux. He has since become a sociologist, novelist, and professor at the London School of Economics, among many other things. He’s been an acclaimed author ever since his early books The Uses Of Disorder, a study of identity and city life, and The Hidden Injuries Of Class, a study of how the effects of class go far beyond material things. All along, however, his interest in craftsmanship and cooperation has endured. Cooperation, he believes, is a craft that diverse societies can, and must, learn.

On Friday, April 13, Sennett will visit Zócalo to deliver a lecture: “Can Diverse Societies Cohere?” at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Grand Avenue. Admission is free. See more details on the award ceremony, sponsored by Southern California Gas Company, here.

Yesterday, Zócalo caught up with Sennett and asked him some questions about his work:

Q. What is the most cooperative setting you’ve ever experienced?

A. For me, it was being on the road as a member of a chamber music group. I had another life as a musician. And, when I was a kid, I toured for several years with different chamber music. Playing music with other people, you either cooperate or the music collapses.

Q.What was your favorite moment with Pierre Monteux?

A. It’s a purely musical story. He was a very short, very elderly man. He couldn’t wave his arms about. He never did that much anyhow. But he had this minute beat, and you focused when you were playing for him on these little flicks of the finger, or little eyebrows being raised. The eyebrows in particular, which he used for cuing, were terrifying. When they went up, you knew your moment had come or else. It was a very intense stare. You could say shaggy eyebrows and a piercing stare are key skills needed for cooperation.

Q. To what society should we who wish to cooperate look for inspiration?

A. I would say to the Scandinavian countries, to Sweden, Norway, Finland. And the reason for that is that these are societies that have made cooperation a way of life. It’s something people don’t have to debate about. They’re vigorous societies economically, all three of them. It’s not that they cooperate because they’re poor. Quite the contrary. I think, with the resources they have, that cooperation has made it possible to spread the benefits of what they’ve got. They’re a real model to me. Americans often think, “Oh that’s socialist.” They’re not in fact socialist. They’re societies that have combined market capitalism with the social ethos.

Q. Can that be credited in part to their relative homogeneity?

A. I think it’s a perceptual issue rather than a statistical issue. If you live in a society where you think that everybody, no matter their skin color or economic class, has basically some common traits that make them Finnish or that make them Italian, then it’s easier to cooperate, because you feel there’s something basic you share which is that national identity. It’s not homogeneity. It’s that there’s some kind of common thread between people. I think a good thing about the United States is we’re beginning to see that common thread in terms of race.

Q. You drop the F-bomb twice in the first sentence of your book. Do you think that might have been the secret to your victory over the competitors?

A. F-bomb?

Q. That’s the term we use, because we’re a family publication.

A. [Laughs.] You don’t sound like a reporter to me.

Q. With what, if any, criticism of Together have you particularly disagreed?

A. I find the biggest misreading of what I’m trying to say is that cooperation is something that’s a moral choice, something you do because you’re such a nice person. That, it seems to me, is really to misunderstand how human societies get constituted, how people develop as children, and so on. If you moralize cooperation, if you say, “I’m a good person, so I cooperate,” you lose the richness of the thing-everything from cooperating on a sports team, in which you’re competing against other people, to warfare, in which people cooperate in order to survive. It loses the complexity of the subject.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s, Amazon.

Send A Letter To the Editors