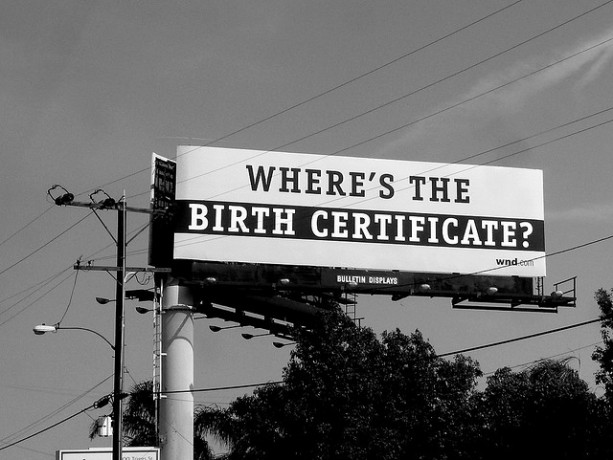

President Obama’s release of his birth certificate, to answer unfounded suspicions about his place of birth, was widely described as an extraordinary act. It wasn’t. Unreasonable demands for birth records are becoming a routine feature of American life.

We like to think that, as Americans, the circumstances of our birth don’t matter. But increasingly we’re acting as if the circumstances of our neighbor’s birth sure do matter – we’ve become obsessed with birth certificates. This obsession predates the Obama presidency, but it is metastasizing now, as fraying social ties, hyper paranoia about security, and fears of cheating combine to undermine our trust in our fellow citizens.

These days, Americans, depending on where they live, can be required to produce birth certificates as a condition of going to school, taking exams, marrying, opening bank accounts, carrying a driver’s license, holding a passport, obtaining a Social Security card, voting or standing for elected office.

Don’t even think of enrolling in kindergarten without a birth certificate, now that strict, new legal deadlines have replaced parental judgment as the basis for when children can start school. As youth sports and competition grow more serious and pre-professional, your child may not be able to play unless you’re willing and able to produce her official birth certificate. And if your skin color or name makes you seem foreign you’d be wise, sadly, to keep your birth certificate close at hand for all sorts of reasons.

Because we are all birthers now.

In this context, President Obama’s longstanding reluctance to release his full original birth certificate might have made him a refreshing symbol of resistance – except for the fact that his government is part of the problem. Heightened immigration enforcement by his administration is fueling demands for birth certificates and other proof of American citizenship. And just weeks before Obama grudgingly surrendered his own birth certificate – with a blast at “carnival barkers” who raised the issue – his own State Department tightened birth certificate requirements for Americans seeking passports (If you don’t have your parents’ full names on the certificate, you can no longer get a passport – unless you go to the trouble of submitting a long list of “secondary” forms of identification in a process that resembles the documentary version of a rectal exam).

In light of big government’s affection for birth records, the demands by the Tea Party conservatives for the president’s birth certificate seem even more dubious. If they were true to their supposed focus on personal liberty, they would have been rallying against the tyranny of mandatory birth registration. After all, our Founding Fathers couldn’t produce birth certificates because they didn’t have them. Neither did Abraham Lincoln. Birth records, when they were kept, were private or church documents. The mandatory, modern birth certificate appeared in Europe in the mid-19th century along with the modern state, which needed to know the identities of its people so they could be taxed and sent off to war.

America was slow to adopt birth certificates, with the U.S. Census bureau nudging the practice along until shortly after World War II, by which time states and local governments had erected the mandatory birth certification regime we have today. For the most part, this is viewed as progress. Birth certificates, in the view of United Nations declarations, are a mark of civilization, a way of guaranteeing the fundamental human right to have a name, a nationality and family ties.

Fair enough, but the American use of birth certificates as a primary form of identification doesn’t make sense, on grounds of privacy or reliability.

I’ve seen the madness of birth certificates personally as a Little League coach for more than 20 years. In fact, there may be no class of people that knows more about the ins and outs of birth certificates than our coaches.

For years, Little League has required coaches to provide copies of birth certificates as proof of age for some players, as a way of preventing cheating through use of over-age ringer. More recently, after facing periodic scandals in its biggest tournaments, Little League added new restrictions. These days, coaches like me must collect official birth certificates with seals, along with credit card and phone bills to prove players live in the right city, and submit them to tournament directors. One unintended consequence of these checks: several cases of identity theft when the binders full of kids’ personal data is lost or stolen.

Little did I know when I first signed up for Little League coaching as a teenager that part of the gig was to demand “papers, please” of families – and to then scrutinize them skeptically like some Communist border guard. Privacy is sometimes violated in mortifying ways. Some years ago, a tournament director tried to disqualify my player because his out-of-state birth certificate did not list a hospital of birth; the Little League official said the certificate might be a fake. He only relented after the boy’s father disclosed details of how he had adopted his son overseas – a fact that shouldn’t have been any of my, or the tournament director’s, business.

Such checks are problematic not only because they violate privacy but also because they don’t work to quell suspicion. Just as believers in President Obama’s foreign birth won’t be swayed by his birth certificate, coaches and players still express suspicions about the true age of six-foot-tall 12 year olds with adult fastballs, even when they’ve produced birth certificates. As in the Obama case, if you can’t beat your opponents on the merits (whether on a sports field or at the polls), it is becoming distressingly common to seek to delegitimize them instead.

Even worse, birth certificate checks aren’t likely to catch cheaters. Birth records are among the easiest identity documents to forge, according to security studies. The information on birth certificates is based on what new parents report, without independent verification. There is no standard format for such certificates, with different states using different formats and including different information. And birth certificates include none of the higher-tech anti-counterfeiting devices and images that have been built into driver’s licenses and passports – documents which, in a deliciously bureaucratic irony, are often drawn up with information from birth certificates.

The continued reliance on birth certificates reveals an essential American hypocrisy. We want to avail ourselves of the privileges of citizenship – the right to participate fully in American civic life, be that at the polls or in our public schools – and to empower the modern state to provide us a safer society, but we balk at the practical steps necessary to meet these demands. So instead of adopting a national ID system, which would be more secure and less burdensome, we have put birth certificates (and drivers’ licenses, with equally problematic results) at the center of an ad hoc, arbitrary system. The lack of clear, one-size-fits-all rules inevitably ends up casting suspicion, and creating special burdens for those who seem somehow foreign. It’s folks with a middle name like Hussein, or who speak other languages, who’d benefit the most from a more foolproof, definitive form of national identification.

The challenge to the president with the funny name won’t be the last time certificates are a political issue. And it’s certainly not the first. The constitution’s requirement that our presidents be “natural born citizens” – that is citizens at birth, or non-naturalized citizens – guarantees disputes over birth. Most famously, legal challenges were launched to the eligibility of Michigan Gov. George Romney – who is Mitt’s dad – in the 1968 presidential campaign because of his birth in Mexico, but he quit the race before they could be adjudicated. (Fearless prediction: the natural born citizens requirement will eventually be eliminated – not because of a charismatic Schwarzeneggerian immigrant, but because some future contender will turn out to have been adopted overseas as an infant by American parents.)

Before he decided to release his own certificate, President Obama shrugged off questions about his birth saying, “I can’t spend all my time with my birth certificate on my forehead.” Neither can the rest of us, Mr. President.

Joe Mathews is Zócalo’s California editor and an Irvine Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation.

*Photo courtesy of paparatti.

Send A Letter To the Editors