Two growing forces in conservative politics are on a collision course: xenophobic nationalism and Mormonism.

The Tea Party movement, with its rejection of Chamber of Commerce-type Republican elites, rose-tinted view of America’s past, and belief in self-reliance and small government, has reinvigorated isolationist nationalism within the GOP. Though much of the movement’s rhetoric has lately focused on public spending, suspicion of all things foreign–be they immigrants, overseas military missions, or Obama’s family roots–is one of the Tea Party’s animating forces.

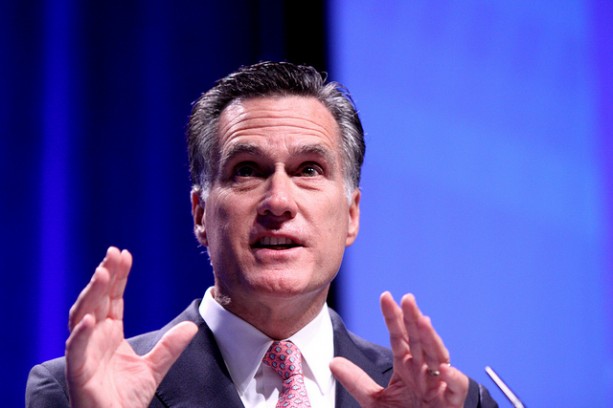

At the same time, we’re in the midst of a Mormon political moment, with two active Mormons vying for the Republican presidential nomination. Though conservatives, Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman are internationalists whose backgrounds suggest they must find it very distasteful to have to pander to the isolationist crowd in their own party.

The notion of a political elite that is more cosmopolitan than party activists is far from a new phenomenon in American politics, but what is startling about the emerging tension within the Republican Party, particularly in the West, is that the counterweight to nativist rancor isn’t exclusively the business elites–but the Mormon church itself.

This makes sense from an institutional point of view. Based on the scale of its enterprise and its future growth prospects, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church)–the official name of the Mormon church–has more in common with a multinational corporation like Coca-Cola or IBM than it does with local evangelical Christian congregations or state-based political activist groups. A president (regarded as a prophet), his two counselors, and a body of twelve apostles may lead the LDS Church from its headquarters in Salt Lake City, Utah, but they recognize that the Mormon doctrine needs to have a global appeal for the enterprise to flourish.

Partly because of the religion’s missionary zeal, Mormons as a whole tend to be more worldly than most Americans. Companies needing multilingual workforces often head for Utah; the CIA has long relied on Mormon hires because so many of them are bilingual (in addition to their straight-arrow reputation). Jon Huntsman is fluent in Mandarin not because he was President Obama’s ambassador to Beijing, but because he did his LDS mission as a young man in Taiwan. Mitt Romney, meanwhile, did his mission in France, though he is as unlikely to reminisce about that on the campaign trail as he is to extol his family’s Mexican roots.

Of the church’s 14 million members, more than half live outside the United States, including a large portion in Latin America who have a personal or familial stake in America’s immigration debates. From Salt Lake City, Church leaders face the difficult responsibilities of managing a global church, and caring for some members living at the margins of U.S. law. Strict enforcement of U.S. immigration policy has disrupted the Church’s internal affairs and upended the lives of some of its members.

Young men and women in the United States who volunteer for missionary work but lack proper documentation cannot safely cross the nation’s borders. Laws designed to discourage illegal immigration can limit the religious freedom of Church members, many of whom came to the United States as children.

In June, two Utah men were arrested and deported, the first to El Salvador along with his family and the second to Guatemala without his family. Both men were serving as the spiritual leaders of their local Spanish-speaking congregations. For a Church that relies on a lay clergy and places special emphasis on family relationships, deportations like these are doubly wrenching.

In this political context, the LDS Church leadership has supported a more permissive approach to immigration policy than that promoted by many other conservatives. The Church endorsed the Utah Compact, a declaration of five principles for a moderate state immigration policy. The Church also played a role in the passage of legislation that grants undocumented workers driver’s licenses and the right to work upon paying a fine. And it went a step further in explicitly tying that endorsement to Mormon religious principles.

This isn’t to say that all Mormon politicians are falling into line: the author of Arizona’s notorious anti-immigrant legislation S.B. 1070, State Senate President Russell Pearce, is a Mormon, and plenty rank-and-file church members in Utah wish their state had followed Arizona’s example. It will be increasingly interesting to see how far the Church goes in flexing its institutional muscle on behalf of a more progressive approach to immigration.

The LDS Church leadership has a proven capacity for motivating its members to take political action on specific policy matters, sometimes across party lines. Though the Church has an official policy of partisan neutrality, it reserves and exercises the right to become involved in specific policy issues. When it does so, the Church can draw on its influence over the beliefs of individual members and on the strength of its corporate structure.

The most recent evidence of the Church’s political power came in the fight over California’s Proposition 8. Here the LDS Church joined with other groups in seeking to outlaw same-sex marriage. In addition to lending support to the coalition at the highest levels, Church leaders mobilized its local members in a coordinated effort to raise funds, get out the vote, and persuade others.

In the process, the Church demonstrated its ability to transform its membership into a highly motivated, local, grassroots political movement almost overnight. And it did so successfully, outside of Utah, in the most populous state in the nation. Though already-conservative members formed the bulk of activists, the Church was also able to draw more moderate members into its efforts. On immigration, and possibly down the line on issues like foreign aid and trade, an internationalist Church leadership would presumably be more at odds with many in its flock than it has been when touting a socially conservative agenda.

The Republican Party is torn these days between its corporate base, which still clings to a more internationalist outlook, and its socially conservative base, which is embracing a more insular worldview–turning first against immigration and trade, and more recently against foreign military interventions as well. It’s surreal to think that, not long ago, a conservative Republican president, George W. Bush, was pushing for comprehensive immigration reform.

His push was ill-fated, but an intriguing question in coming years will be whether Mormon political activism may have an unexpected moderating influence on the right, insofar as the Church allies itself with business elites to push back against the xenophobic politics of the Tea Party.

Jason LaBau is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West (ICW). He is currently at work on a book project, Phoenix Rising: Arizona and the Enduring Divisions of Modern Conservatism.

*Photo courtesy of Gage Skidmore.

Send A Letter To the Editors