This summer I moved back to my boyhood house in San Mateo, California, after 48 years living elsewhere, mostly on the east coast and in China. My California-born wife and I are Golden State chauvinists of the sentimental kind. We have framed orange crate labels on our walls. We choke up when we hear “California Dreamin’” on the radio.

San Mateo looked pretty much the same. But I found I wasn’t recapturing the simpler days of my youth. When I started reconnecting with favorite spots like my old high school, I encountered complexities and advances I had not expected, particularly after the many headlines about California in decline.

The little house where I grew up on Voelker Drive still has no garbage disposal, no dishwasher, and no air-conditioning. But my brother Jim, the computer teacher at Baywood Elementary School, set up a Wi-Fi system and satellite TV. I felt up-to-date until I visited my alma mater, Hillsdale High School, a sprawling campus two blocks away on Alameda de las Pulgas.

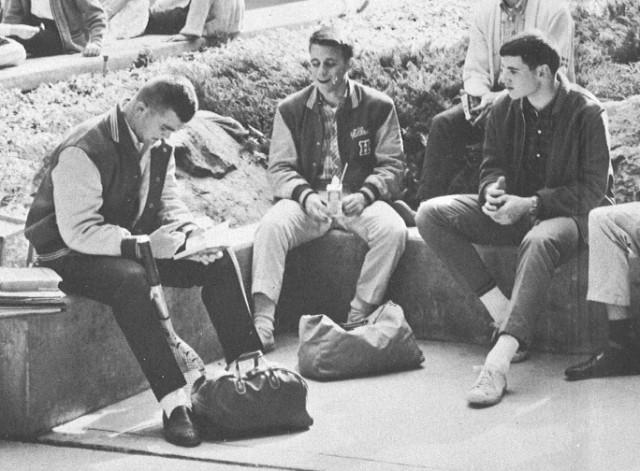

I write about education for The Washington Post and its web site. High schools are my specialty. Suburban schools like Hillsdale rarely if ever change, except in their ethnic mix. Hillsdale was about 95 percent white when I graduated in 1963. Today the 1,343-member student body is 45 percent white, 30 percent Latino, 15 percent Asian, 4 percent Filipino, and 2 percent black. About 20 percent are low income, roughly what it was when I was there.

That is a typical demographic shift for a California suburban school, and not what makes it so startling to visit Hillsdale now. Through many twists and turns, while I wasn’t paying attention, it has become one of America’s first 21st century schools.

I often make fun of that label. Attempts to describe what 21st century schools look like often make them seem like 20th century schools with better equipment and fancier mission statements. Hillsdale, by contrast, has changed significantly the way students are taught, and raised the level of instruction for both kids going to college and kids not sure what they want to do.

Getting there wasn’t easy. A team of educators who were part of the transformation helped put together a manuscript, written by social studies teacher Greg Jouriles, that explains the process. The changes happened in the same unpredictable way that the computer and Internet revolution swept San Mateo and much of the rest of the Peninsula.

The term “Silicon Valley” did not exist when I graduated from Hillsdale. I still find it hard to believe that the ratty shops of El Camino Real and the nondescript warehouses along U.S. Highway 101 are backdrops for a now famous international center of commerce and innovation. That public schools, among our most change-resistant institutions, might be similarly altered is even more surprising.

At Hillsdale students are organized into small advisory groups that meet daily with a staff member trained to help them with any problems–a system pioneered by private schools. The ninth and tenth grades are divided into three houses that focus on interdisciplinary lessons and ambitious projects such as a recreation of a World War I battle and a trial of Lord of the Flies author William Golding. Students of all achievement levels are mixed in the same classes, sharing in discussions but doing different homework based on their needs and wishes. All seniors must define an essential question, write a thesis of at least eight pages, and defend it before a panel of graders including outside experts. More changes are planned. The idea is to do much more than prepare students for the annual state tests, but the changes have helped raise the school’s Academic Performance Index on California’s 1000-point scale from 662 in 2002 to 797 this year.

Mixing students of different achievement levels in the same classes and giving them different homework is extraordinarily rare in American public schools. Defending research work before a panel of experts is what happens in graduate school, not high school.

True, the football team is not doing as well as it did when it was led by my 25-year-old gym teacher, future Super Bowl coach Dick Vermeil. The Knights this year are 2-4. Like with everything else at the school, the faculty is looking for solutions, while enjoying the fact that the Friday night games, as in my day, have stands full of students and parents, a loud and boisterous band, and tasty hot dogs.

There is something else that connects the new era with the old. When I first moved into our San Mateo house in 1952 and enrolled in third grade, one of my classmates was a big kid named Don Leydig. He was kind, smart, and the best all-around athlete I had ever met. We became friendly rivals for good grades. He made places for me in baseball, basketball, and flag football games where I would not embarrass myself. At Hillsdale, he became the shining light of our 1961 championship football season, Vermeil’s best player as a halfback, and the league’s most valuable player.

Leydig played freshman football at Stanford under another future Super Bowl coach, Bill Walsh, but realized he wasn’t fast enough for the varsity and focused on his studies. He was in the Peace Corps in Libya, then returned to the Peninsula and built a splendid reputation as a high school history teacher, coach, and administrator. In 1989 he became Hillsdale’s principal.

Many coaches and teachers remembered him. They were happy to have as a boss one of the most talented and respectful kids they had ever taught. Don told me, “They would have done anything for me.”

He understood the importance of the American high school. It defines our national character as the last educational experience we share before some of us go to college and others to work. Leydig knew our high schools were in a slump. American 17-year-olds have shown no significant gains in reading and math achievement in the last three decades. Challenging courses are rare. Nationally, the average teenager does less than an hour of homework a night.

According to Jouriles’ written account of Hillsdale’s transformation, Leydig did not charge into the school waving a banner of reform and knocking down the opposition. Instead he renewed old relationships and got to know new people, using the modesty and thoughtfulness that made him so popular when we were students. He hired teachers with ideas for reform and let them make changes. He worked with the teacher’s union. He forged ties with the Stanford University education school, particularly its nationally renowned reform expert Linda Darling Hammond. He cut shop classes and secretarial slots to have more resources for the reforms. He let new ideas start small to iron out flaws. He got grants and finessed district budget rules. At crucial moments he forged consensus with surveys of teacher opinion that did not ask simply if they were for or against a change, but instead gave a range of choices. Were they for it with qualifications? Could they live with it? Were they against it but wouldn’t quit over it?

The change at Hillsdale came in spurts, with some backsliding. It was a team effort, like our class’s football wins. It was hard for everyone, including Leydig. Jouriles describes the afternoon an assistant principal and a teacher called faculty leaders to a secret meeting at a pub on 25th Avenue in hopes of getting the principal fired.

It didn’t work. Leydig’s recruiting helped produce a new generation of school leaders, including innovative teacher Jeff Gilbert who now leads the school. Leydig retired in 2005 and heads the Hillsdale Foundation, raising money to keep the changes alive. He often travels to coach administrators and advise on school redesign. There are a few other thriving California efforts to remake schools such as the New Tech Highs and High Tech Highs. But Hillsdale is the most advanced homegrown project I know of.

Leydig and I sometimes sit together at football games. Still trim, he avoids the hot dogs and cupcakes while I gorge myself. We enjoy the noisy, colorful stream of young people passing by. They seem like our classmates from 1963–from all levels of the income scale, happy to be together on a warm night. They no longer know the words to the fight song, but they have something better: lively, accessible teachers and a widening knowledge and appreciation of the challenge and excitement of the world outside.

Don and I loved the old Hillsdale. But if you ask us where we would like to send our grandchildren, the new Hillsdale gets our vote.

Jay Mathews, a Washington Post education columnist and the father of Zócalo’s California editor, is the author of eight books, including Work Hard, Be Nice: How Two Inspired Teachers Created the Most Promising Schools in America.

*Photos courtesy of Jay Mathews.

Send A Letter To the Editors