In November 2010, Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County, Arizona, created an armed “immigration posse” to interdict suspects. Its members included Hollywood action-movie figures such as Steven Segal and Lou Ferrigno and a Phoenix man, Wyatt Earp, who was widely reported to be not only the namesake but also the nephew of the iconic Old West gunfighter. This reporting required considerable imagination, since Earp had two nephews, both born in the 1870s, and both long dead. The 21st-century Earp is a retired insurance agent whose strongest connection to the original Earp is that he has portrayed him in a one-man play.

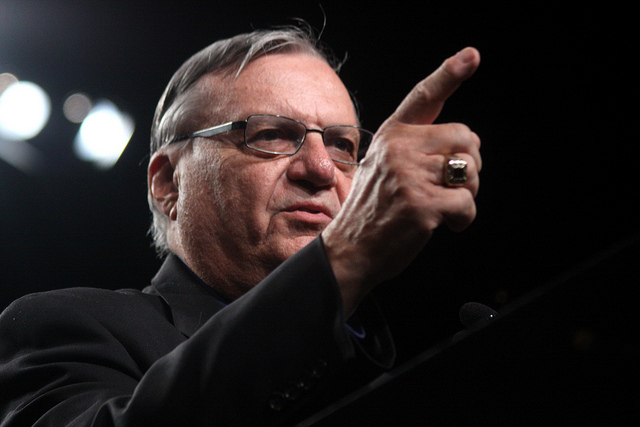

Arpaio’s attempt to link himself to Earp may seem desperate, but it’s not surprising. Arpaio is a master of symbolic politics, manipulating Western iconography to present himself as a lawman who, like Wyatt Earp, would impose his version of justice at all costs. The power of sheriffs, particularly in the parts of the Western United States where they are elected officials, is inextricably tied up in the concept of a popular justice that is not bound by anything so mundane as the law.

Like Arpaio, Earp was an Arizona man. He was deputy sheriff of Pima County in the last half of 1880; served episodically as a deputy on the Tombstone city police force in 1881 (when he was in the famous “gunfight at the O.K. Corral”); and was commissioned as a deputy U.S. marshal in early 1882. Like Arpaio, who has published two books touting himself as “America’s toughest sheriff,” Earp learned how to use the media to his advantage. He spent most of his last two decades in Los Angeles, becoming a fixture at Hollywood studios and telling exaggerated tales of his exploits.

Earp demonstrated his willingness to place justice above the law particularly starkly in 1882, when he led a posse through southern Arizona in search of the men who had murdered his brother. The posse captured two men and summarily executed them. One of the men killed, Florentine Cruz, was probably the wrong guy. Accused of murder, Earp fled Arizona.

Earp’s role as a rogue marshal–a vigilante with a badge–became a crucial part of his status in American popular culture. It’s of course ironic that a vigilante killer and accused murderer would become a symbol of rectitude, but Earp’s story appealed to Americans who, like him, saw justice not in fickle courtrooms but in the character of stalwarts who were willing to break the law–even to commit murder.

Earp was a central figure in movies in the first half of the 20th century, a period when roughly a third of all Hollywood films were Westerns. A 1930 novel of the Wyatt Earp story by W.R. Burnett (best known for the gangster drama Little Caesar) became, in 1932, the film Law and Order, starring Walter Huston. The publication in 1931 of an adoring Earp biography became, three years later, the film Frontier Marshal.

At a time when the leaders of organized criminal syndicates were at the height of their power and celebrity, these early-1930s versions Earp cast him as a kind of Eliot Ness, an example for the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s battle against organized crime. During the early years of the Cold War, Earp became a symbol of resistance to communism. The anti-communist Earp reached its apogee in a 1953 remake of Law and Order, starring Ronald Reagan as the lawman. Reagan’s lawman confronts a corrupt gang that controls a small town through terror and intimidation. (The gang’s leader has a metal hand; he literally rules with an iron fist.)

Film has rooted Wyatt Earp in American collective memory, and almost anyone, including retired Phoenix insurance agents and county sheriffs, can tap into it. (Recall when President George W. Bush vowed to get Osama bin Laden “dead or alive” in 2001.) In sum, sheriffs like Arpaio derive their power not from careful enforcement of the law but from disdain for it. This style of sheriff politics can be entertaining–but it has real consequences.

In 1993, in a demonstration of his resolve not to release prisoners because of overcrowding, Arpaio constructed an outdoor annex to his county jail that has come to be known as ‘Tent City.” Over the past 19 years, nearly half a million people, many of whom were merely awaiting trail, have been confined in the tents, even when summer temperatures have reached the triple digits. In 2010, when the state of Arizona passed Senate Bill 1070 mandating identification checks of suspected illegal immigrants, Arpaio announced a new “Section 1070” in Tent City to accommodate the additional anticipated arrivals. In December 2011, the civil rights division of the Justice Department charged Sheriff Arpaio with unfairly targeting Latinos.

Sadly, this is all to be expected. County sheriffs are among the few law enforcement officers in the industrialized world who are elected to office. The mixture of law enforcement and local politics has bred a type of popular justice that carries an enormous potential for demagoguery and the abuse of power–and, potentially, many a latter-day Florentine Cruz.

Andrew Isenberg is a professor of history at Temple University and the author of a forthcoming biography of Wyatt Earp.

*Photo courtesy of Gage Skidmore.

Send A Letter To the Editors