How do you make an American poet?

California’s new poet laureate, Juan Felipe Herrera, answered that question with laughter, singing, storytelling, and poetry as he recounted his life and work during an event sponsored by the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs.

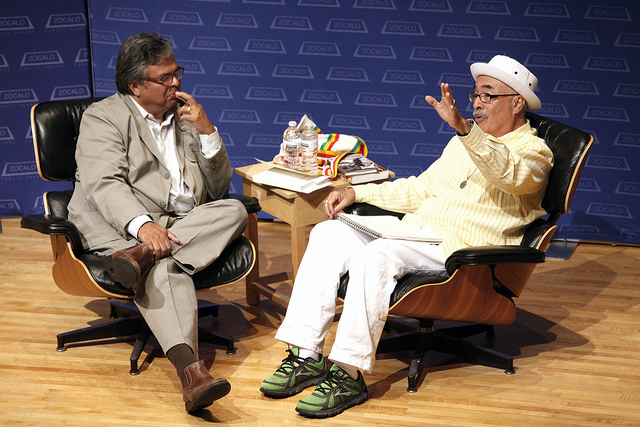

The evening’s moderator, KPCC News Editor Oscar Garza, introduced Herrera–to not one but two rounds of applause from the large audience at MOCA Grand Avenue–by quoting from the introduction to Half of the World in Light, a 2008 anthology of new and selected work. Herrera, according to the introduction, is “‘a uniquely American writer whose ethnicity conditions his ars poetica without constraining it.’”

Garza then asked Herrera how his appointment as poet laureate came about. Herrera recalled his interview with Governor Jerry Brown, who asked him about T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” and how it applies to our society–and specifically California–today. Herrera said of Brown: “He was interested in poetry. He was interested in society,” and not just in connecting poetry to society, but culling knowledge from a poem and applying it to social ills.

This is the same reason Herrera said he decided to become a poet when he arrived at UCLA on scholarship in 1967: “To bring about change through poetry.”

But long before he decided that poetry would be a vocation, words meant something to him. Herrera, while breaking into song, recalled his mother’s songs and lullabies–corridos she sang about revolution and desperation.

An only child, Herrera grew up moving around California with his parents, who worked in the fields of farms across the state. This transient life came with solitude and isolation, but he didn’t recall these years as unhappy or difficult. “I didn’t see a hard life,” he said. “No one complained.”

Sometimes they didn’t have the chance. Herrera said he never forgot watching his friends and their parents taken out of the house they owned by the border patrol, “never to be seen again.” It was, he said “a big moment. I lost my friends.” From then on, his family moved from city to city, although he saw it as an adventure. He recalled marveling at the majesty of train stations and visiting his aunt in San Francisco–who ran a “Mexicatessen”–and his cousins, who taught him about boxing and jazz.

Herrera’s parents spoke Spanish, and as a young writer he wrote in English with some Spanish. Today he writes almost exclusively in English. Did you consciously decide, asked Garza, to write in English?

Herrera recalled how wild and electrifying it was to write in “Chicano-Pachuco-English-Spanish” as a young writer. It felt, he said, like being “in the core of the belly of the universe in a sense.” But writing only in English felt “just as wild, it was just as new and explosive.”

Garza asked Herrera to discuss the inspiration for his poem about Mexican-American life, “Exiles of Desire.” The poet recalled writing it in Seattle (where he had traveled “on a love quest”) with some inspiration from Munch’s “The Scream.” He wrote the poem, he said, because Mexicans in the U.S. “were exiled yet we didn’t have the status of exiles. I thought that was an interesting state to be in.”

Herrera said his writing process is fluid. “Revision? There’s no such thing,” he said. “You can’t revise the universe. It happened already.” Pressed on how he can resist revision, he said that it didn’t work for him when he tried.

“I enjoy letting it all hang out and writing,” he said. He also likes experimenting with different styles and media. He showed the audience a notebook with handwritten pages in a large font size, and another page with a poem that looked like a diagram. He likes when poetry spills over into visual art and photography, dance and theater. “The freer the better,” he said.

One of the few times he struggled to write–that he felt conscious about writing–was when he wrote about the L.A. riots after watching them on television from Fresno in 1992. It was “one of the first times I kind of saw myself writing,” he said. “It was a tough poem to write because I kind of got into it, and I kind of got out of it at the same time.”

The audience asked Herrera to get even more personal in the question-and-answer session. Among the questions were his favorite John Coltrane album (Settin’ the Pace is one of them), his thoughts on the death of his former publisher, Sandy Taylor of Curbstone Press (whom he recalled fondly), and his memories of the 1973 Festival de Flor y Canto at USC (“that was like the Chicano Woodstock”).

The final question came back to what it means to be an American writer, and an American in 2012. How does he define Americanness?

“I think every one of our communities has had that question, all the writers,” he said. Jewish-American writers dealt with this issue in the 1940s before reaching a turning point in the 1950s. Latino writers, he said, have reached that same turning point in the 21st century: They are able to write as writers.

Watch full video here.

See more photos here.

Read poets’ reflections on what makes a powerful poem here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors