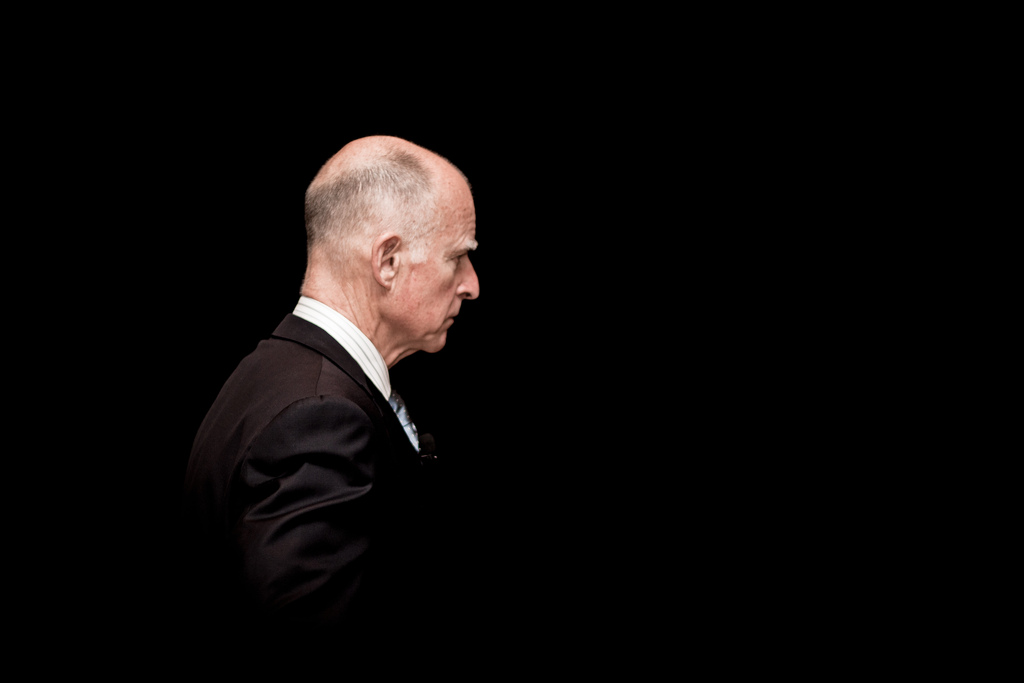

As California’s oldest governor, Jerry Brown has gone out of his way to demonstrate his vigorous good health, jogging around the Capitol and even challenging reporters to pull-up contests—which he won. Now that he’s been diagnosed with prostate cancer and begun radiation therapy, some news outlets seem to be experiencing a bit of schadenfreude, gleefully calling the 74-year-old governor’s diagnosis a “blow to his healthy image.”

They missed the real story, which isn’t the governor’s prostate cancer but rather the fact that he has chosen to be treated at all. Given a choice between no treatment and radiation therapy, it’s a bit of a toss-up as to which is more likely to do him harm, and it’s entirely possible he didn’t really understand there was a choice.

That might seem like an outrageous claim, but here’s why it’s not. The governor’s office has released precious few details about his diagnosis, but his doctor did say that the cancer was “early-stage” and “localized.” About half of prostate cancers that fall into that category—early-stage and localized—never would have caused symptoms in the patient’s lifetime, even if they were left untreated.

Only about 3 percent of deaths among men are due to prostate cancer—probably less than most people imagine. But a lot of men have prostate cancer and never know it. Autopsy studies of men who died of other causes have found that about 60 percent of men in their 70s have prostate cancer that was not diagnosed. For men in their 80s, that number goes up to 70 percent. In other words, more men die with prostate cancer than from it. That means there’s a good chance the governor has been overdiagnosed and is going through treatment for a cancer that would never have bothered him, or that could have been treated successfully at a later date if and when it started causing symptoms.

To make matters worse, Brown’s radiation treatment has a good shot at turning Governor Healthy into a patient who will suffer serious, life-altering side effects. The most common, long-lasting side effects of radiation therapy are bloody stools or rectal pain and other bowel problems; urinary obstruction, pain, or irritation, and other urinary difficulties; and erectile dysfunction. About half of men who undergo radiation therapy suffer one or more of these problems long-term. A few even die from their treatment.

This is the terrible conundrum that many men face when diagnosed with low-risk, localized prostate cancer. Should they be treated, and risk becoming candidates for Viagra and Depends? Or should they forego treatment and face the smaller risk that their cancer will go on to become aggressive and maybe even kill them?

Such personal decisions have implications far beyond the health of California’s governor. The state and private insurers could save a lot of money by refusing to pay for treatment for low-risk, localized prostate cancer, and the end result would be only a few additional deaths per year from prostate cancer, if any. Payers could save even more by refusing to cover the P.S.A. test, a blood test that is used to screen asymptomatic men for signs of early prostate cancer. Since it was first put into widespread use in the 1990s, the P.S.A. test has led more than a million men to be diagnosed and treated for a cancer that could have been ignored; many experts now believe it should not be used as a screening test.

Of course, no insurer would dare to make such a draconian move. There is another way to give men choices, reduce the number of men who are harmed by overdiagnosis and overtreatment, and save some money. It’s called “shared decision making.” In this process, doctors provide patients with digestible, balanced information about the potential benefits and harms not only of the P.S.A. test and prostate cancer treatment but also of a wide variety of elective procedures and tests. Then, the doctor and the informed patient decide together how to proceed.

That’s not what usually happens. In the case of the P.S.A. test, one-third of men who get one are never asked if they want it. Of men who are asked, two-thirds say their doctor failed to mention possible downsides that result from treatment that can follow screening.

When doctors share decisions with their patients, by first offering them accurate, balanced information, and then asking them about their values and preferences, patients often make very different choices. In the case of prostate cancer, many men choose to forego the P.S.A. test. Men who have been diagnosed with a localized cancer often choose not to be treated, but rather to watch and wait.

Let’s hope the governor is one of the lucky ones whose cure does not turn out to be worse than the disease. An even better outcome would be if he also realizes the need to get shared decision making into widespread practice.

Send A Letter To the Editors