For every missing link scientists find, they joke that two more pop up to takes its place. Yet thanks to fossils found at the far ends of the Earth—as well as the stars in our solar system—we know more about humanity’s origins than ever before. University of Chicago paleontologist Neil Shubin is one of the people who has made important discoveries about where we come from. Shubin visits Zócalo to explain how he and other scientists can read our history from the ground beneath our feet and the skies up above. Below is an excerpt from his book, The Universe Within: Discovering the Common History of Rocks, Planets, and People.

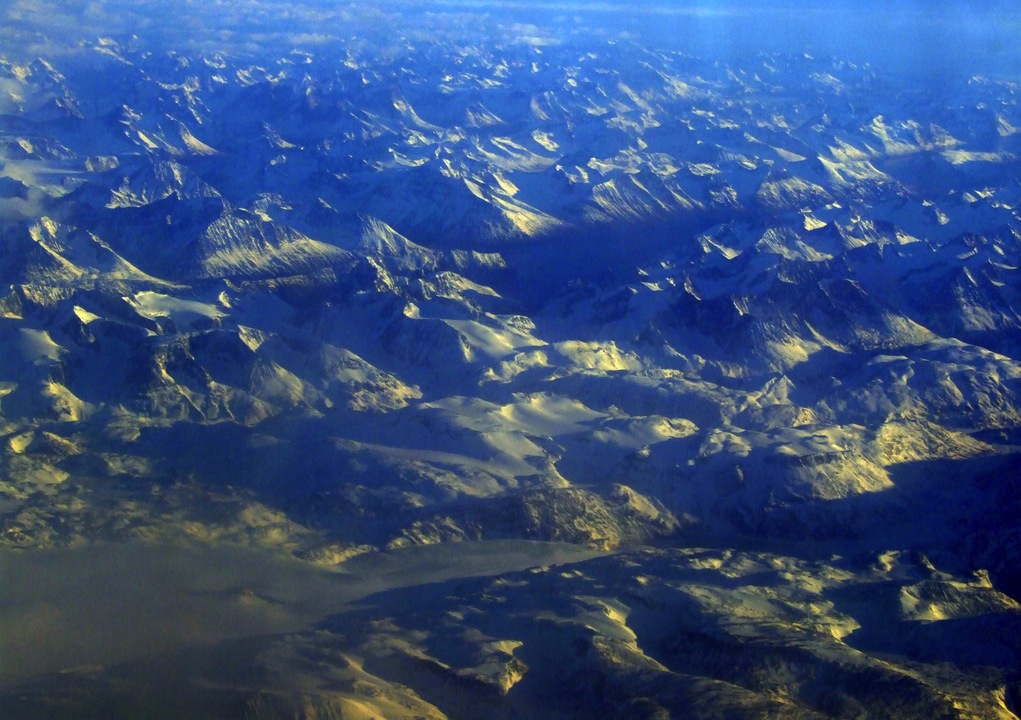

Viewed from the sky, my companion and I must have looked like two black specks perched high on a vast plain of rock, snow, and ice. It was the end of a long trek and we were slogging our way back to camp on a ridge sandwiched between two of the greatest ice sheets on the planet. The clear northern sky opened a panorama that swept from the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean in the east to the seemingly boundless Greenland Ice Cap to our west. After a productive day prospecting for fossils, an exhilarating hike, and with the majestic vista around us, we felt as if we were walking on top of the world.

Our reverie was abruptly cut short by a change in the rocks beneath our feet. As we traversed the bedrock, brown sandstones gave way to ledges of pink limestone that, from our earlier discoveries, became an auspicious sign that fossils were in the neighborhood. After a few minutes of peering at boulders, alarm bells went off—my attention was pulled to an unusual glimmer flashing from a corner of a melon-sized rock. Experience in the field taught me to respect the sensation triggered by these moments. We traveled to Greenland to hunt for small fossils, so I hunched over my magnifying lens to scan the rock closely. The sparkle that arrested me sprung from a little white spot, no bigger than a sesame seed. I spent the better part of five minutes curled up with the rock close to my eyes before passing it to my colleague Farish for his expert opinion.

Concentrating attention on the fleck with his lens, Farish froze solid. His eyes shot back to me with a glare of pent up emotion, disbelief, and surprise. Rising from his crouch, he took off his gloves, and launched them about 20 feet in the air. Then, he nearly crushed me with one of the most titanic bear hugs I have ever received.

Farish’s exuberance made me forget the near absurdity that this excitement came from finding a tooth not much bigger than a grain of sand. We found what we had spent three years, countless dollars, and many sprained ligaments looking for—a 200-million-year-old link between reptiles and mammals. But this project was no miniature trophy hunt. The little tooth represents one of our own ties to worlds long gone. Hidden inside these Greenlandic rocks lies our deep connection to the forces that shaped our bodies, the planet, even the entire universe.

Seeing our connections to the natural world is like detecting the pattern hidden inside an optical illusion. We encounter bodies, rocks, and stars every day of our lives. But train the eye and these familiar entities give way to deeper realities. When you learn to view the world through this lens, bodies and stars become windows to a past that was vast almost beyond comprehension, occasionally catastrophic, and always shared among living things and the universe that fostered them.

How does such a big world lie inside this tooth, let alone our bodies? The story starts with how we ended up on that frozen Greenlandic ridge in the first place.

*

Imagine arriving at a vista that extends as far as the eye can see knowing you are looking inside it for a fossil the size of the period that ends this sentence. If fossil bones can be small, so too are whole vistas relative to the immensity of the earth’s surface. Knowing how to look for past life means learning to see rocks not as static objects, but as entities with a dynamic and often violent history. It also means perceiving our bodies, as well as our entire world, as representing just moments in time.

The playbook that fossil hunters use to develop new places to look has been pretty much unchanged for the past 150 years. It is as simple as it gets: find places on the planet that have rocks of the right age to answer whatever question interests you, rocks of the type likely to hold fossils, and those exposed on the surface. The less you have to dig the better. This approach, which I described in Your Inner Fish, led my colleagues and I to find a fish at the cusp of the transition to life on land in 2004.

As a student in the early 1980s, I gravitated to a team who had developed tools to make headway finding new places to hunt fossils. Their goal was to uncover the earliest relatives of mammals in the fossil record. The group had found small shrew-like fossils and their reptilian cousins in a number of places in the American West but, by the mid 1980s their success brought them to an impasse. The problem is best captured by the jest, “each new missing link creates two new gaps in the fossil record.” They had done their share of creating gaps and were now left with one in rocks about 200 million years old.

The search for new sites is aided by economic incentives: with the potential for significant oil, gas, and mineral discoveries there are economic incentives for countries to map the geology exposed inside their borders. Consequently, any geological library in the country holds maps, journal articles, and other reports detailing the age and geology of the rocks exposed on the surface. The challenge is to find the right maps.

Professor Farish A. Jenkins, Jr. led the team at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Fossil discovery was the coin of the realm for his crew and it started in the library. Farish’s laboratory colleagues, Chuck Schaff and Bill Amaral, were key in this effort; they had honed their understanding of geology to predict likely places to make discoveries and, importantly, they trained their eyes to find really small fossils. Their relationship often took the form of one long friendly argument—one would propose a new idea while the other would relentlessly try to quash it. If the idea held up to their amiable tit-for-tat, then they would then both line up behind the proposal and take it to Farish, with his keen logistic and scientific sense, for vetting.

One day in 1986, while chewing the fat with Chuck, Bill found a copy of the Shell Oil Guide to the Permian and Triassic of the World on Chuck’s desk. Paging through the volume, Bill spotted a map of Greenland, with a little hatched area of Triassic rocks on the eastern coast at a latitude of about 72 North, roughly that of the northernmost tip of Alaska. Bill kicked things off by proclaiming that this could be a prime next area to work. The usual argument ensued, with Chuck denying that the rocks were the right type, Bill responding, and Chuck countering.

By complete dumb luck, Chuck had the means to end the debate right on his bookshelf. A few weeks earlier, he was trolling through the library discards and pulled out a paper entitled the Triassic of East Greenland, authored by a team of Danish geologists in the 1950s. Little did anybody know at the time but this freebie, saved from the trash heap, was to loom large in our lives for the next 10 years. The minute Bill and Chuck looked at the maps in the reprint, the debate was over.

My graduate student office was down the hall and, as was typical for that time in the late afternoon, I would swing by Chuck’s office to see what’s what. Bill was hovering about and it was clear that some residue remained in the air from one of their debates. Bill didn’t say much, he just slapped Chuck’s geological reprint down in front of me. In it was a map that showed exactly what we had hoped for. Exposed on the eastern coast of Greenland, across the ocean from Iceland, were the perfect kinds of rocks to find early mammals, dinosaurs, and other scientific goodies.

The maps looked exotic, if ominous. The east coast of Greenland is remote and mountainous. And the names evoke explorers of the past: Jameson Land, Scoresby Sund, and Wegener Halvø. It didn’t help matters that I knew that a number of explorers had perished during their trips there.

Fortunately, the expeditions that transpired ultimately rested on Farish, Bill, and Chuck’s shoulders. With about 60 years of field work between them, they had developed a deep reservoir of hard-earned knowledge about working in different kinds of field conditions. Of course, few experiences could have prepared us for this one—as a famed expedition leader once told me, “There is nothing like your first trip to the Arctic.” I learned plenty of lessons that first year in Greenland, ones that were to become useful when I was to run my own Arctic expeditions 11 years later. With leaky leather boots, a small used tent, and a huge flashlight in the land of mud, ice, and the midnight sun, I made so many bad choices that first year I remained smiling only by reciting my own motto, “Never do anything for the first time.”

The most tense moment of that first trip came when selecting the first base camp. This decision has to be made in a fleeting moment while flying in a helicopter. As the rotors turn, money flies out the window: the costs of Arctic helicopters can be as high as 3,000 dollars per hour. On a paleontology budget, geared more to beat-up pickups than Bell 212 Twin Hueys, that means no wasting time. Once over a promising site revealed by the maps back in the laboratory, we check off a number of important properties rapidly before setting down. It is a long list: we need to find a patch of ground that is dry and flat, yet still close to water for our daily camp needs, far enough inland so that polar bears aren’t a problem, shielded from the wind, and importantly, near exposures of rock to study.

We had a good idea of the general area from the maps and aerial photos and ended up setting down on a beautiful little patch of tundra in the middle of a wide valley. There were little creeks from which we could draw water. The place was flat and dry so that we could pitch our tents securely. It even had a gorgeous view of a snowy mountain range and glacier on the eastern end of the valley. But we would soon discover a major shortcoming. There were no decent rocks within easy walking distance.

Once camp was established to our satisfaction, we set off each day with one goal in mind: find the rocks. We’d climb the highest elevations near camp and scan the distance with binoculars for any of the exposures that figured so prominently in the paper Bill and Chuck found. Our search was made doable by the fact that the targets were collectively known as “red beds” for their characteristic hue.

With red rock on our minds, we went off in teams; Chuck and Farish climbing hills to give them views of the southern rocks, Bill and I setting off for places that would reveal those to the north. Three days into the hunt, both teams returned with the same news. Out in the distance, about six miles away to the northeast, was a sliver of red. We’d argue about this little outcrop of rock, scoping it with our binoculars at every opportunity for the remainder of the week. Some days, when the light was right, it seemed to be a series of ridges ideal for fossil work.

It was decided that Bill and I would scout a trail to get to the rocks. Not knowing how to walk in the Arctic, and with my unfortunate boot selection, the trek turned out to be an ordeal; first through boulder fields, then across small glaciers, and pretty much through mud for the rest of the way. The mud formed from wet clay made an indelicate glurp as we extricated our feet each step. No footprint remained, only a jiggling viscous mess where our feet had just been. Mud, while inconvenient, never scared me. During glacier crossings I often heard roaring water under our feet—a raging river under the ice.

After three days of testing routes, we plotted a viable course to the promising rocks. With a four-hour hike, the red sliver in our binocular view from camp turned out to be a series of cliffs, ridges, and hillocks of the exact kind of rock we needed. With any luck, bones would be weathering out of the rock’s surface.

The goal now became to return with Farish and Chuck, doing the hike as fast as possible to leave enough time to hunt for bones before having to turn back home. Arriving with the whole crew, Bill and I felt like proud homeowners showing off our property. Farish and Chuck, tired from the hike but excited about the prospect of finding fossils, were in no mood to chat. They swiftly got into the paleontological rhythm of walking the rocks at a slow pace, eyes on the ground, methodically scanning for bone at the surface.

Bill and I set off for a ridge about half mile away that would give us a view of what awaited us even further North. After a small break, Bill started to scan the landscape for anything of interest: our colleagues, polar bears, other wildlife. He stopped scanning and said, “Chuck’s down.” Training my binoculars on his object, I could see Chuck was indeed on hands and knees methodically crawling on the rock. To a paleontologist this meant one thing—Chuck was picking up fossil bones.

Our short amble to Chuck confirmed the promise of the binocular scan; he indeed had found a small piece of bone. But our hike to this little spot had taken four hours and we now had to head back. We set off on the hike with Farish, Bill, Chuck, and I in a line about 30 feet apart. After about a quarter of a mile something on the ground caught my eye. It had a sheen that I’d seen before. Dropping to my knees like Chuck an hour earlier, I saw it in its full glory, a hunk of bone the size of my fist. To the left was more bone, to the right even more. I was in a bone field of some huge animal. I called to Farish, Bill, and Chuck. No response. Looking up, I knew why: they were also on their hands and knees. We were all crawling in the same colossal field of broken bones.

At summer’s end, we returned boxes of these fossils to the lab where Bill put them together, like a three dimensional jigsaw puzzle. The creature was about 20 feet long with a series of flat teeth, a long neck, and small head. The beast had the diagnostic limb anatomy of a dinosaur, albeit a relatively small-sized one.

This kind of dinosaur, known as a prosauropod, holds an important place in North American paleontology. Dinosaurs in eastern North America were originally discovered along streams, railroad lines, or roads: the only places with decent exposures of rocks. The eminent Yale paleontologist Richard Swann Lull (1867-1957) found a prosauropod in a rock quarry in Manchester, Connecticut. The only problem is that it was the back end. The block containing the front end, he was chagrined to learn, was earlier incorporated into the abutment of a bridge in the town of South Manchester. Undeterred, Lull described the dinosaur from its rear end only. Only when the bridge was demolished in 1969, did other fragments come to light. Who knows what fossil dinosaurs remain to be discovered deep inside Manhattan? The island’s famous brownstones townhouses are made of this same kind of rock.

Knowing the past kindles sublime connections. The hills in Greenland form large staircases of rock that not only break boots but also tell the story of the stone’s origins. Hard layers of sandstones, almost as resistant as concrete, poke out from softer ones that weather away more quickly. Virtually identical staircases lie further south: matching sandstones, siltstones, and shales extend from North Carolina to Connecticut all the way to Greenland. These layers have a distinctive signature of faults and sediment; they speak of places where lakes sat inside steep valleys that formed as the earth fractured apart. The pattern of faults, volcanoes, and lake beds in these rocks is almost identical to the great rift lakes in Africa today—Lake Victoria and Lake Malawi—where movements inside the earth cause the surface to split and separate, leaving a gaping basin filled by the water of lakes and streams. In the past, rifts like these extended all the way up the coast of North America.

From the beginning, our whole plan was to follow the trail of the rifts: knowing that the rocks in eastern North America contained dinosaurs and small-mammal like creatures gave us the A-Ha moment with Chuck’s geological reprint. That, in turn led us north to Greenland. Then, once on Greenland we pursued the discoveries on the ground like pigeons following a trail of breadcrumbs. It took three years, but clues in the red beds ultimately led us to that frozen ridge I trekked with Farish.

Send A Letter To the Editors