The buzzword tsunami that is “big data”—a handy way of describing our vastly improved ability to collect and analyze humongous data sets—has dwarfed “frictionless sharing” and “cloud computing” combined. As befits Silicon Valley, “big data” is mostly big hype, but there is one possibility with genuine potential: that it might one day bring loans—and credit histories—to millions of people who currently lack access to them. But what price, in terms of privacy and free will (not to mention the exorbitant interest rates), will these new borrowers have to pay?

In the not-so-distant past, the lack of good and reliable data about applicants with no credit history left banks little choice but to lump them together as high-risk bets. As a result, they either were offered loans at prohibitively high rates or had their applications rejected.

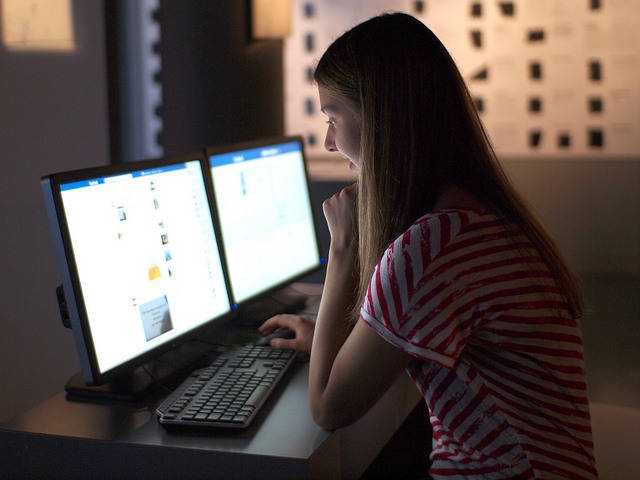

Thanks to the proliferation of social media and smart devices, Silicon Valley is awash with data. While much of it has no obvious connection to finance, some of it can still be used to make accurate predictions about the user’s lifestyle and sociability. As a result, a new generation of companies is beginning to deploy algorithms that sieve through these data to separate trustworthy borrowers from those likely to default and to price their loans accordingly.

Some—like the Hong Kong-based Lenddo, which currently operates in the Philippines and Colombia—do so by scrutinizing the applicants’ connections on Facebook and Twitter. The key to getting a successful loan from Lenddo is having a handful of highly trusted individuals in your social networks. If they vouch for you and you get the loan, your select friends will also be notified of your successes in repaying the loan. (In the past, Lenddo even threatened to notify them—exerting maximum peer pressure—if you had problems repaying the loan.)

Similarly, the U.S.-based LendUp, which hands out short-term loans with high interest rates while allowing its most trusted established clients to move to more attractive longer-term packages, looks at social media activity to ensure that factual data provided on the online application matches what can be inferred from Facebook and Twitter. Not surprisingly, most such startups—including Lenddo and LendUp—are financed by the same venture capitals who have backed much of the social media boom. (Accel Partners, one of the first investors in Facebook, has funded Lenddo; LendUp has received support from Google Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz.)

Social media is just the tip of the iceberg. Wonga, an extremely ambitious online payday-lending company based in London, even considers the time of the day and the way a candidate clicks around the site in determining whether to grant her a loan. It rejects two-thirds of all first-time applicants. Kreditech, a Germany company that seeks to provide “scoring as a service,” looks at 8,000 indicators, such as “location data (GPS, micro-geographical), social graph (likes, friends, locations, posts), behavioral analytics (movement and duration on the webpage), people’s e-commerce shopping behavior and device data (apps installed, operating systems).”

Those without smartphones or Twitter accounts need not despair. Even simple cellphones are sources of data with great predictive value. Thus, Safaricom, Kenya’s largest mobile operator, studies how often its customers top up their airtime, how regularly they use the voice service, and how frequently they use the mobile money function. Once their trustworthiness has been established, Safaricom would gladly lend them money. But mobile operators moonlighting as banks aren’t the only ones leveraging these data: A Cambridge-based startup called Cignifi is using the length of calls, the time of the day, and the location of the call to guess the lifestyle—and hence the reliability—of loan applicants in the developing world.

All these efforts are premised on the sensible idea that current models of assessing creditworthiness focus on too few indicators, shutting off many potential borrowers who pay their bills on time but don’t have good (or any) credit histories. “Big data” can separate the lazy slackers from those who truly deserve better loan terms. The goal, then, is to get as many data as possible, perhaps even nudging potential applicants to preemptively disclose as much information about themselves as possible. In yet another puzzling paradox of the modern age, the rich people are spending money on expensive services that protect their privacy and improve their standing in Google’s search results, while the poor people have little choice but to surrender their privacy in the name of social mobility.

Google and Facebook are often touted as the models to emulate in this business. As Douglas Merill, Google’s former chief information officer and the founder of ZestFinance—a startup that leverages “big data” to provide credit scoring information—told The New York Times last year: “We feel like all data is credit data, we just don’t know how to use it yet. This is the math we all learned at Google. A page was important for what was on it, but also for how good the grammar was, what the type font was, when it was created or edited. Everything.” To that effect, ZestFinance looks at 70,000 signals and feeds them into 10 separate underwriting models for assessing the risk. The results of those models are then compared—in milliseconds—and an applicant’s risk profile is generated. If only East Germany’s Stasi—the true pioneers of “big data”—had the same model for assessing potential dissidents!

All of this sounds wonderful, and some of these startups do seem to be led by social entrepreneurs who want to make credit more accessible to the masses. That said, this field is not without its controversies: Online payday lenders like Wonga have been used of having their ads displayed in a children’s game, of targeting students with predatory lending offers, and of hiring government officials to help them survive increasing scrutiny of their activities by the regulators.

But what happens once these firms, having figured out that all data are credit data, realize that all data are also marketing data? Given how much they know about their clients, it would be very hard for such lending companies not to use this information to sell their existing customers on yet another loan or, perhaps, encourage them to use the loan to take advantage of some unique online sales offer. Wonga, for example, has recently embarked on a partnership with a furniture retailer, whereby customers get the option to pay for the furniture they buy later and in installments—courtesy of Wonga and its high interest rates. Might it get tempted to make this purchase irresistible to those lucky few who happen to be browsing at the wrong place at the wrong time?

Given how much they know about their clients, these companies can perfect the art of hidden persuasion and manipulation in ways that Madison Avenue could never even dream of. LendUp—co-founded by a former executive at the online game giant Zynga—already relies on techniques of “gamification” to reward its customers for paying their loans on time. Might they also rely on such techniques to get them to borrow more often?

So far, many in this industry downplay such moral hazards. Wonga’s founder told the Jewish Chronicle last year that he doesn’t believe that people can ever be convinced to borrow money that they don’t need. “[Our clients] have a cash-flow challenge and need a solution. We are not asking them to take credit they don’t need. You don’t generally get sold things on the Internet. You have to go and search for something. It’s not the same as someone coming to your door and selling you something that you may or may not need.”

It takes a very brave—or short-sighted—man to argue that we are never sold things we don’t need. (I’m looking at you, Amazon!) This is especially true when we’re dealing with companies that know more about us than our families do—and that make money by, well, having us borrow money and buy stuff. Is it just the usual Silicon Valley naivete? Or is good-old Wall Street greed hiding behind the cyber-utopian rhetoric?

Do we need a “big data” lending equivalent of the Glass-Steagall act, which separated commercial from investment banking before being repealed in 1999? Perhaps it’s too early for such drastic interventions. But it’s not too soon to for the regulators to start thinking about ways to separate the use of “big data” for assessing trustworthiness and its subsequent reuse for marketing new financial products. Making loans accessible to millions of the previously unbankable customers is a noble goal. Getting them hooked to such loans isn’t.

Send A Letter To the Editors