Mexicans were stunned, and united, by the news last week. Across all segments of society, conversations invariably turned to the same subject. “Can you believe it?” people would ask each other, as if for confirmation. “La Maestra (“the teacher”), arrested?” The conversations were sprinkled with plenty of “wows” and shaking of heads of the well-I-suppose-anything-is-possible variety.

“La Maestra” is Elba Esther Gordillo, who headed Mexico’s national teachers’ union until her arrest Tuesday evening after descending from her private jet at an airport outside Mexico City. She has long been one of the nation’s top power brokers and one of the most powerful union bosses in the world, presiding over Latin America’s largest union (with a membership of 1.5 million teachers) as if it were her family business.

It had long been speculated that President Enrique Peña Nieto, sworn into office in December, might attempt to take on Gordillo, but her arrest on embezzlement charges still came as a shock. In a society known for powerful special interests, none seemed more special or untouchable than “La Maestra,” whose brazen flaunting of her ill-gotten gains seemed to prove her untouchability. Strangely, even blatant corruption can appear to be legitimized by transparency.

One scene in the Mexican education documentary De Panzazo compiles footage of annual speeches by Gordillo going back to the 1970s. It reveals that little ever changed about Gordillo’s rhetoric or bombastic style, but there are significant differences in her wardrobe and the contours of her face, which took on radically new shapes with each successive plastic surgery.

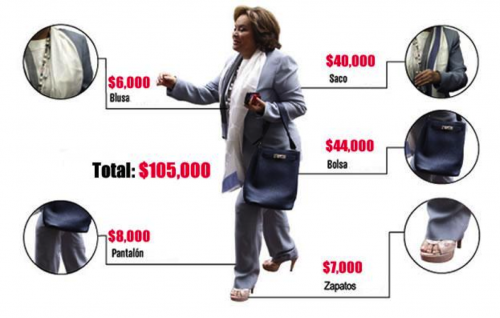

Gordillo, 68, reportedly earned an average annual income of $86,000 from 2009 to 2012. However, this infographic by the website Animal Politico reveals that a single outfit cost more than three times her monthly salary. (The figures are in Mexican pesos.)

Mexico’s attorney general alleges that Gordillo and two associates embezzled more than $150 million (yes, that’s dollars, not pesos) of union funds between 2008 and early 2012. They claim to have evidence that links those embezzled funds to $3 million in purchases at Neiman Marcus, $2 million to purchase two homes in San Diego, $1.4 million to finance her private jet, and $17,260 to plastic surgery clinics in San Diego. Among the more amusing headlines in the Mexican papers last week—it’s hard to remember this is at heart a tragedy, not a comedy—was “Neiman Marcus to Cooperate with Investigation.”

Again, the shock here has nothing to do with the allegations. I don’t know of any Mexican who is surprised by them. Indeed, most Mexicans expect that their leaders embezzle public funds. The shock is that for once, the culture of impunity has not prevailed, as evidenced by images of a confused-looking Gordillo behind bars.

Skepticism abounds, too. When Mexico Assistant Attorney General Alfredo Castillo appeared on a television news show following Gordillo’s arrest, he was asked how it was possible that Gordillo’s many acts of embezzlement were not detected by authorities until now.

“You would have to ask the previous administration,” responded Castillo.

Indeed, it is assumed that the previous administration of President Felipe Calderón never investigated Gordillo’s blatant corruption because he owed his presidency to her. Mexico’s teachers’ union controls nearly 2 percent of the electorate. Calderón won the 2006 election by less than 1 percent, and in 2011 Gordillo admitted that a pact with Calderón guaranteed the union’s support of his candidacy in exchange for key government positions. In last year’s presidential election, Gordillo ran her own candidate.

There is a recent tradition of Mexican presidents offering a dramatic opening gesture to prove who’s boss in the aftermath of close elections. Skeptics point to the 1989 arrest of Joaquín Hernández Galicia, the corrupt leader of the oil workers’ union just a month after President Carlos Salinas de Gortari took office. The symbolic arrest did little more than consolidate the new president’s power and redirect spoils; Salinas’ administration was notoriously corrupt. Similarly, Calderón, eager to consolidate his own power in 2006, donned a military uniform and declared war against the drug cartels during his first week as president.

The day after Gordillo’s arrest, the president made televised comments claiming that her detention was “strictly legal,” and that the law “applies to everyone equally, and no one can be above the law.” Critics, however, point to the failure of the attorney general’s office to prosecute former governors Manuel Cavazos Lerma and Eugenio Hernández Flores, whose money laundering charges were dropped the same day that Gordillo was detained. They also question how the government can justify the detention of Gordillo but not Carlos Romero Deschamps, the equally notorious leader of the oil workers’ union who made headlines earlier this week after giving his son a Ferrari reportedly worth $2 million.

What does Gordillo’s arrest mean for Mexico and its struggling schools? There is widespread recognition that Mexico’s education system is in dire need of reform if the nation is ever to fulfill its promise. Gordillo was a key obstacle to implementing recently passed education reform that, theoretically, will make it easier to replace underperforming teachers. Optimists are hopeful that her arrest marks the first step toward a systematic approach to dealing with corruption and institutionalized political patronage that allows teachers’ union members to sell their jobs, or even bequeath them to relatives.

Claudio X. González, the president of Mexicanos Primero, which co-produced the documentary De Panzazo, insists that it is crucial not to lose focus of the necessary structural reforms during the inevitable media circus that will follow Gordillo’s prosecution. “What must change,” writes González, “is the system. If we’re not able to achieve that, this will be a wasted opportunity for the administration and for all Mexicans.”

In their much acclaimed book Why Nations Fail, development economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson seek to explain the key factors that distinguish the development of poor and rich countries. The opening chapter paints a portrait of Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora, two communities that share the same culture, history, and geography. Their difference, and the difference between all poor and rich countries, according to the authors, is that the political and economic institutions of Nogales, Arizona respond to the needs of the majority of residents, while Nogales, Sonora is ruled by a narrow, untouchable elite that prevents the distribution of resources and opportunities.

It’s unlikely, but one can only hope that Gordillo’s detention could represent the first step toward dismantling the systematic corruption and spoils—patronage that has hampered Mexico’s development since its founding.

Send A Letter To the Editors