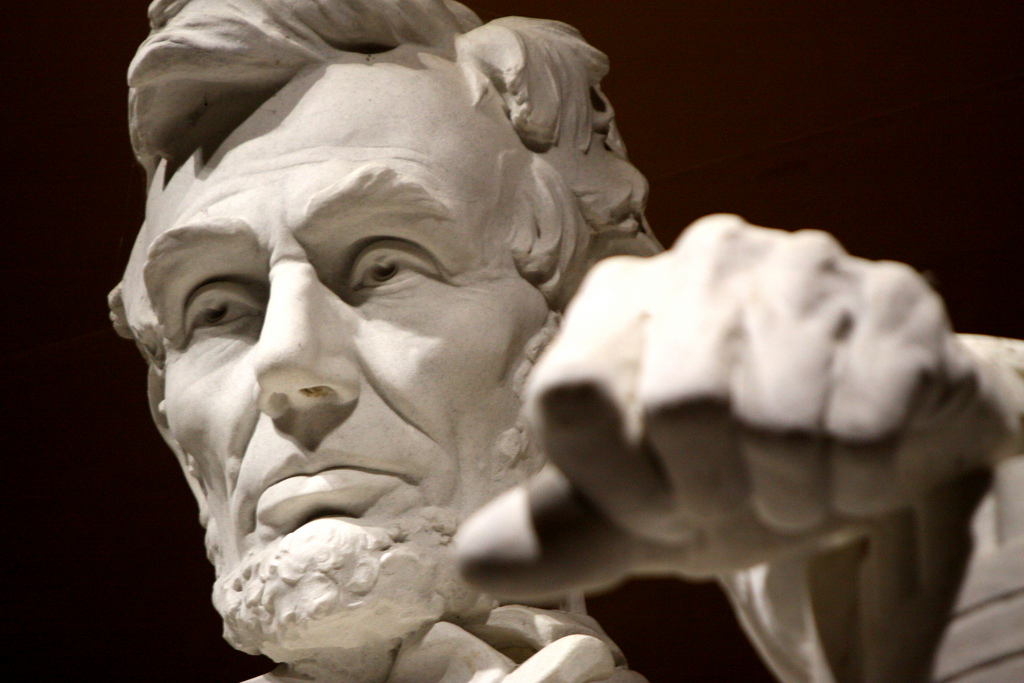

Abraham Lincoln never ordered a drone strike. Nor was he ever forced to determine exactly when the government should Mirandize a terror suspect. Yet he confronted all kinds of dilemmas about how the rule of law applies during times of crisis. Despite the vast differences between the Civil War president’s age and ours, Lincoln’s approach to these types of challenges offers a valuable insight about constitutional decision-making.

Americans routinely invoke the “separation of powers” when describing constitutional authority, but that phrase has been misunderstood, particularly in the context of national security. The phrase “separation of powers” itself never appears in the Constitution. Instead, over the years, we have translated Montesquieu’s great enlightenment principle in ways that political scientist Richard Neustadt famously summarized as “separated institutions sharing powers.”

As commander-in-chief, Lincoln went even further in parsing the great constitutional principle. He followed what might be termed a “chronology of powers.”

In April 1861, Lincoln expressed no doubt that secession was rebellion and that ordinary criminal proceedings were inadequate to stop the Confederates. Since Congress was out of session, he took action, authorizing the use of military force and suspending habeas corpus, as the Constitution provides, “when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” Not everyone agreed. The president’s toughest critic was Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, who warned publicly that Lincoln had usurped what should have been congressional war powers on a mere “pretext” that left the American people “no longer living under a Government of laws.” Unbowed, the president took this argument to Congress. In a message from July 4, 1861, Lincoln recounted his decision-making process in painstaking narrative detail, concluding that he had “so far, done what he has deemed his duty.” “You will now,” he added, “according to your own judgment, perform yours.”

Congress did perform its duty, in fits and starts, and sometimes in ways that hampered the president. Yet throughout the war, Lincoln accepted congressional oversight. Whatever secrets he kept from them—such as his plans for emancipation—he kept quiet only for a matter of weeks or months, not years, and never through an election cycle. Nor was this a battle played out only behind closed doors. Lincoln went public frequently with plain-spoken arguments on behalf of his administration’s most controversial policies. He engaged his critics. When questioned over the source of authority for his most sweeping executive actions, Lincoln responded, “I think the constitution invests its commander-in-chief, with the law of war, in time of war.” When opponents charged that such reasoning represented a first step towards tyranny, Lincoln fought back with metaphors, claiming that just because “a particular drug” was “not good food” for a healthy man, it did not mean that it was “not good medicine for a sick man.”

He also accepted judicial review of his initial war-making efforts in the only notable Supreme Court case of the conflict, The Prize Cases (1863), which ended up approving his actions, over Chief Justice Taney’s bitter objections. The majority decided the president was “bound to meet” the grave national security threat “without waiting for Congress to baptize it with a name.” Finally, Lincoln never canceled a single election, even in the summer of 1864, when nearly everyone believed his reelection effort was doomed. “We cannot have free government without elections,” he stated simply.

This is the chronology of powers. Lincoln understood that presidents must sometimes assert practically unlimited initiative in the name of public safety. Yet he conceded what advocates for a strong presidency often do not—that with such great initiative comes the need for even greater accountability. Only with true oversight can Congress react in ways that limit executive actions during periods of crisis. This is essentially a political process—a series of arguments about policy—but after this political contest has been fully joined, then the federal courts must also apply legal standards in order to review legitimate claims of individual harm. Most important, however, the people themselves must eventually decide what rights they are willing to sacrifice in the name of national security—and to whom. Regular elections are the ultimate American bulwark against tyranny.

Such a model offers much-needed perspective but no easy answers. Nobody knows what Lincoln would do today. In the midst of the Civil War, he could appear unyielding. During one of his more plain-spoken moments, he asserted that the government should have “seized and held” Robert E. Lee and other high-ranking secessionists even before they had committed any crimes, because they “were nearly as well known to be traitors then as now.”

Would he have tossed them into Gitmo or authorized drone strikes against them if he had those capabilities? Maybe. But maybe not. Despite all of his tough talk, Lincoln was also committed to upholding international law, or what he called the “law of war.” Surprisingly, perhaps, Americans in those days seemed to take international law more seriously than we do. The Supreme Court cited international legal theory in The Prize Cases, and the Lincoln Administration issued its own handbook on international laws of war, known as the Lieber Code, which later became a significant precedent for The Hague and Geneva conventions of war.

In other words, like everybody else, Lincoln found it challenging to navigate a proper balance between liberty and security. That did not stop him, however, from making tough decisions on his own initiative and, more important, from then making his case directly to the American people.

Certainly no president since Lincoln has been as well situated to offer a thoughtful rationale for executive initiative as Barack Obama, a former editor of the Harvard Law Review and constitutional law professor at the University of Chicago. Yet he now authorizes targeted killings as a commander-in-chief while remaining unaccountably mute about his weighty constitutional responsibilities. In his most recent State of the Union address, delivered on Lincoln’s birthday in February, the president promised that “in the months ahead” his administration would be “even more transparent” about how “our targeting, detention, and prosecution of terrorists remains consistent with our laws and system of checks and balances.” Yet he has not kept that promise.

During the short-lived Senate filibuster in March over the drone program’s secrecy, the administration essentially lawyered up by sending out the attorney general to dismiss Senator Rand Paul’s various concerns regarding weaponized drones as “entirely hypothetical.” Last month, the administration went even further, declining to send anyone to testify before the Senate’s first official hearing on the “drone wars.” Senator Richard Durbin, the chair and a leading Democrat (who once represented Abraham Lincoln’s old congressional district), felt compelled to express his “disappointment” at the administration’s refusal to cooperate.

If Lincoln taught us anything, it is that words matter, especially in times of crisis. Presidents need to make arguments as well as decisions. They cannot delegate profound questions about war powers to the lawyers but must provide a clear rationale for their actions. President Lincoln certainly performed his duty in this regard. The question is, when will President Obama perform his?

Send A Letter To the Editors