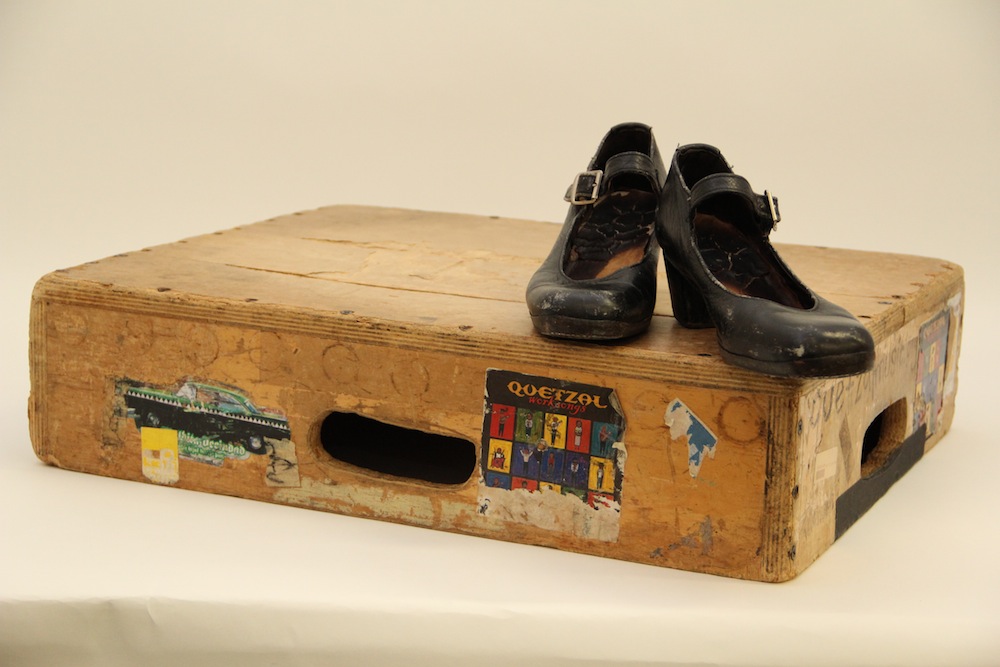

The annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival was in full bloom on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in late June. Audiences flocked to different stages and exhibits that shared the finest music cultures in the world. As I approached the workers’ trailer, I knew it was the last time I would hold my tarima (stomp box) and old zapateado shoes. I’d participated with my band Quetzal in a moving tribute concert to legendary folk singer Pete Seeger the previous evening, and it would be the last time I used my shoes and tarima. Now, these “artifacts” were headed to the Smithsonian. They, like Seeger, had been instruments of social change in their own right, and symbolized the multitude of musical influences that shaped me while I was growing up in Los Angeles.

I was born to immigrant parents from Mexico. My mother was from Tijuana, and my father was born and raised in Guadalajara, Jalisco. They met at the bailes (dances) that newly arrived immigrants frequented in downtown L.A. hotel ballrooms in the late 1960s. They decided to settle in California and start a family.

I was born to immigrant parents from Mexico. My mother was from Tijuana, and my father was born and raised in Guadalajara, Jalisco. They met at the bailes (dances) that newly arrived immigrants frequented in downtown L.A. hotel ballrooms in the late 1960s. They decided to settle in California and start a family.

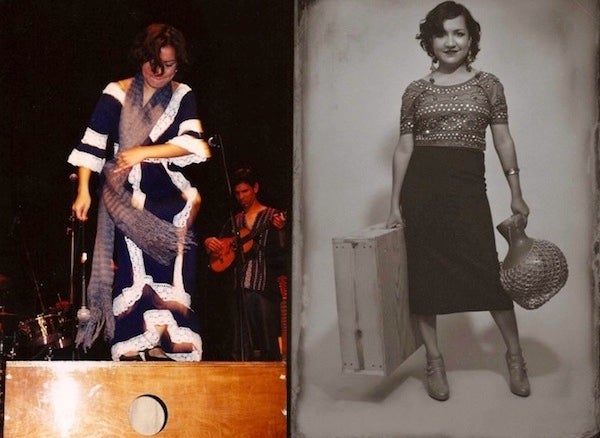

Music was at the center of our household. My father loved music, but was unable to live the life of a professional musician. Instead, he lived vicariously through my older brother’s innate talents. At an early age, my brother began to participate in the Mexican variedades (variety shows) that toured California. When the shows stopped at the historic Million Dollar Theatre in downtown L.A., my sister Claudia and I were encouraged to join my brother by singing harmonies—segunda. Our show became known as Gabrielito González, La Actuación Infantil, the “Children’s Act.”

It was a lucrative time for the Mexicano musical life in Los Angeles. Lucha Villa, Mercedes Castro, Aída Cuevas, Vicente Fernández, Federico Villa, and Yolanda Del Rió were some of the artists for whom we had the privilege to open. I still remember running on the Million Dollar Theatre’s sticky floors, through the backstage wings, while dodging rattraps. The smell of stale popcorn and nachos lingered in the air as we listened to the mariachis tune up in the basement.

My family spent a great deal of time in “Dog Town,” the William Mead Homes projects north of downtown. There, I was exposed to the art of street dancing—popping, locking, and breaking, while listening to early hip-hop like Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force. It is also where I was introduced to the power of music and dance in community.

I was 11 years old when my father left us, and although he was absent for the rest of my life, I inherited most of my musical interest from him. Our family had little money for formal musical training, so my mother sought out free extracurricular activities, most of which had an artistic or musical bent. At ballet folklórico mexicano classes, I first learned zapateado, a group of dance styles that involve striking your feet to rhythms from Mexican states like Jalisco, Nayarit, Zacatecas, and Michoacán. However, the music and dances of Veracruz, with its Afro-Mexican influence, was most fascinating to me. I would revisit the music and dance from this state many years later with the resurgence of a participatory music and dance practice known as fandango.

In the late 1990s, I was introduced to the fandango, a fiesta comunitaria (community fiesta) that produces the music popularly known as the son jarocho. Fandango has been my greatest rhythmic influence ever since, and I have joined my partner Quetzal (after whom our band is also named) and other community organizers in disseminating it. The son jarocho is rooted in indigenous, Spanish (Andalusian), and African cultures. Slave economies initiated by New Spain in the 17th century allowed for these cultures to mix and give birth to a unique music and dance culture that continues to thrive to this day.

Fandango is exercised as ritual celebration in honor of a town’s patron saint or at other community events such as weddings, baptisms, and funerals. Eventually, I adapted the style of zapateado fandanguero—a mix of fandango-rooted inflections blended with other African-derived rhythms—to the music of Quetzal, along with the many other styles of music and dance I studied as an undergraduate in ethnomusicology at UCLA. Koblah Ladzekpo introduced me to the sounds of Ghana; Francisco Aguabella, Scott Wardinski, and Teresita Dome Perez introduced me to Afro-Cuban traditions. My feet and hands started beating out an alchemy of these influences. What I learned with hands on drums I then translated to feet on wood.

You can hear and see all this in compositions such as Quetzal’s “Planta De Los Pies” (from our 2003 Sing the Real album). The cadence of the rhythms I tap out with my feet is in a typical, syncopated fandanguero style, but I stamp it out in a non-traditional 11/8 meter. I add a more pronounced sway to the hip and body movements than is traditional. And I do all this while I sing, in Spanish, “Although I really like the colors of [Mexico’s] sound, I feel my cadence is my own because the Chicano always invents.” There’s the context of heritage, and then there’s each person’s own voice. This experimental spirit has infused Quetzal’s collaborations with other artists interested in the son jarocho such as Ozomatli in “La Segunda Mano” for their studio album Don’t Mess With the Dragon.

Rhythms, like memories, travel to inform and influence new moments, people, and generations. The rhythms I play and dance met on the American continent and made it their home. I think of it as my duty to continue to share them with our audiences and with my students.

As I handed over my shoes and tarima, memories like these flashed before my eyes. I glanced for the last time at the rugged stomp box, now marked and scuffed with the wear and tear of countless trips. Who would have guessed that a small 4-by-6-foot plywood box and a pair of old black leather and tire-tread shoes would be significant to the National Museum of American History? The shoes and tarima reflect the life, effort, and labors of a daughter of Mexican immigrants contributing to this nation, as many others have. They were my tools. And I feel proud of the life and opportunities we found together, of the sounds we evoked upon this soil, for and about humanity.

Send A Letter To the Editors