During the 2013-14 school year, Quintin Boyce, the principal of Bioscience, a public high school in Phoenix, took a portion of his discretionary budget and told students they could decide how it was spent. He set no rules, except that the projects should benefit the school community. He knew many things could go wrong, but trusted that the students were going to assign those resources with responsibility and fairness.

This was a historic experiment—to the best of our knowledge, it was the first time that American high school students had used a process called participatory budgeting that we, as scholars of participatory democracy, have studied. But the Bioscience budgeting was more than history—it was an answer to the broader problem of participation.

Americans are often told to participate in local democratic decision-making, but we are rarely told how. And so most of us don’t know how. Effective participation requires knowledge of local laws, regulations, and processes. Participation also demands skills like active listening, public speaking, negotiation, conflict resolution, open-mindedness, compromise, and willingness to move from self-interest to the common good. Since none of these are innate, these civil and democratic competencies must be learned somewhere. Like schools.

The idea of schools as a place to produce democratic citizens is an old one, but it has been little practiced. Schools seldom nurture the capacity to participate in local democracy, and civics curricula have eroded over the past two generations.

To counter this trend, some educational institutions have begun trying to reach democracy through democratic processes. Bioscience is an interesting case. It is a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) public high school with approximately 300 students of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The student population is more than 60 percent Latino, and roughly two-thirds of students qualify for the free and reduced meals program. Bioscience teachers emphasize project-based, student-centered learning through exploration and inquiry.

This atmosphere and comfort with experiential learning made Bioscience a favorable environment for launching a school participatory budgeting project. Participatory Budgeting, or PB, is a democratic process of deliberation and decision making over budget allocations that started in 1989 in Porto Alegre, Brazil. It is currently implemented in more than 1,500 cities around the world. Participatory budgeting provides not only a more transparent and accountable way of managing public money but also a means for participants to learn more about their community.

In the U.S., the first participatory budgeting process took place in Chicago in 2009. PB has since been used in New York; Greensboro, N.C.; San Francisco; Long Beach; Boston; and post-bankruptcy Vallejo, California. Although each process is different, participatory budgeting tends to follow a similar structure. In the first phase, residents identify local needs, brainstorm potential ideas to address these needs, and elect delegates to represent individual communities in deliberations. In the second phase, delegates discuss their communities’ priorities and formulate project proposals. Then, delegates bring these proposals to the community for a vote. The most popular projects are funded and implemented, and the process begins in the next year or budget cycle.

Although participatory budgeting is normally implemented at the municipal level, there have been participatory budgeting experiments in other settings (like public housing) and with specific age groups. For instance, Boston is in the second year of a participatory budgeting project that allows teens and young adults to decide together how to allocate $1 million of the city’s budget.

At Bioscience in Phoenix, which broke ground as the first school to implement participatory budgeting with students, the democratic work began with the design of the process itself. First, each grade level elected four student representatives to a steering committee. This committee of 16 students created the rules for the PB process and invited all students to submit proposals. In the first year, a total of 45 students collaborated on preparing 30 proposals.

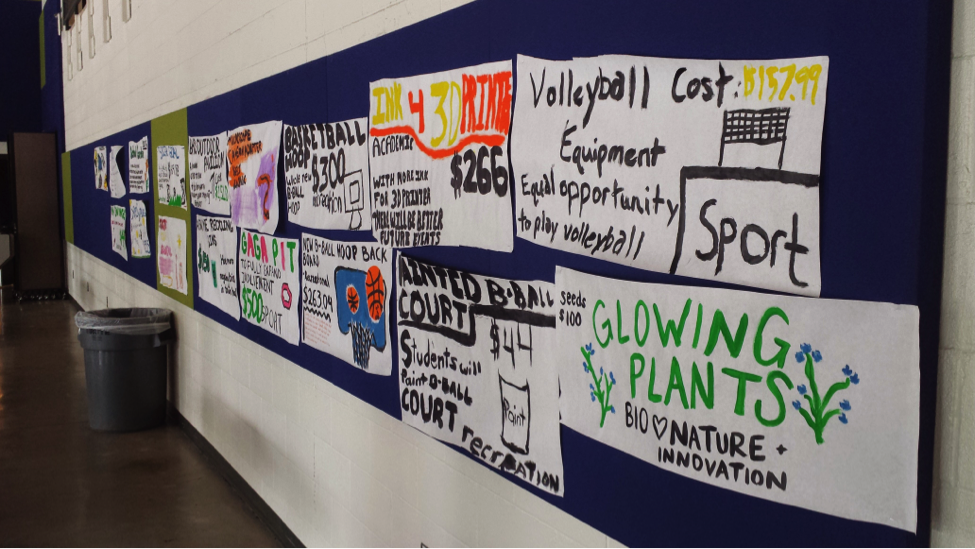

In the next phase, the steering committee refined the final pool of projects to 18 by eliminating incomplete proposals and designed promotional materials to inform all students about the competing projects. Students hung posters in the school cafeteria that described the 18 projects and their total costs, everything from $157 for volleyball equipment to $1,000 to fund a music club, and from $217 for a school garden to $740 for shade umbrellas in the school courtyard.

More detailed project descriptions were shared in class at each grade level, and a slide show presentation of the projects was posted on the school’s internal social media site. At forums divided by grade level, steering committee members led discussions about each project so that students could ask questions and debate the merits of each option. Finally, the steering committee distributed ballots in each class to their peers. All students were given the option to vote on their three favorite projects. The steering committee tallied the votes and submitted the results to their principal. Throughout the process, nearly the entire student body participated in some form.

The three projects that received the most votes were educational in nature. The first was a sustainability education display for the school’s courtyard, the second was color ink for a student-built 3-D printer, and the third funded camera adapters for laboratory microscopes. The three most popular projects exceeded the PB budget by a few hundred dollars, but Principal Boyce was so enthusiastic about the way the process unfolded that he agreed to fund all three options. Reflecting on the experience, he told us he felt honored to provide an opportunity for students to participate in the improvement of the school community, and he hopes this experience will inspire students to engage in—and change—their communities.

At the end of that school year, Dr. Boyce was transferred to another school, and there was some concern that the incoming principal would cancel the experiment. But incoming principal DeeDee Falls decided to continue the process. The second cycle of participatory budgeting is currently underway. At this early stage, students are brainstorming ideas like soccer goals, a bike share program, and an aquaponic system and an algae reactor to produce biofuel. Principal Falls told us that this process makes sense for a school like Bioscience that tries to involve students in many aspects of their educational process. For her, participatory budgeting is valuable because it encourages students to collaborate with their peers and make meaningful decisions, together.

What better way to learn democracy than by doing it?

Send A Letter To the Editors