When traveling by air, rail, or bus across country on business or pleasure, I always recall the summer of 1961, when the Freedom Rides made interstate travel the democratic activity we take for granted.

Racial segregation on trains or in bus stations is unthinkable today. But I remember the days when it was the law or custom in many places, especially in the South. I was raised in New Orleans, and learned early from family what segregated life was like as a Negro and would probably be like for the rest of my life. I also remember the Freedom Rides. In August 1961, I was one of a group of 11 men and women who boarded a train from Los Angeles to Mississippi.

We Freedom Riders—some 400 or so people across the U.S.—bore witness to our conviction that segregation was illegal. We were a disciplined, organized, and racially mixed group. We rode trains, buses, and planes; we sought service at dining facilities, restrooms, and waiting rooms. And more often than not, we were arrested and jailed for violation of local laws. We expected to be incarcerated and were aware that there could be violence directed against us. But we were committed.

Fifty-four years have passed since that summer—but just last weekend, I joined Ellen Broms from the L.A. Freedom Rider group in Sacramento. We traveled together to memorial services for poet and fellow Freedom Rider Steve Sanfield. We joined Steve’s family, friends, and admirers at the North Columbia Schoolhouse Cultural Center in Nevada City, California, site of the Sierra Storytelling Festival that Steve founded 30 years ago.

When I met him, Steve was working at the historic Larry Edmunds Bookshop in Hollywood. He was a recent graduate of Amherst College in Massachusetts. He was gentle, an articulate man of conscience.

I had recently graduated from UCLA, where I was active in the L.A. chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). As a student, I served as a CORE liaison with student activists in the South. We spoke often by phone about what was going on there and how we could support their causes from Los Angeles. After graduation, I continued this work with CORE—talking and collaborating with like-minded people like Steve and Ellen who sought an end to segregation and racial injustice in Los Angeles and across the nation.

We closely followed the Freedom Rides after they started in May. Riders were beaten and jailed, and a bus was firebombed outside of Anniston, Alabama. Students from Tennessee vowed that this violence would not stop the rides, and the movement picked up steam over the summer as activists joined them from across the U.S. in Jackson, Mississippi.

By August, the Freedom Rides were slowing down as focus shifted to action in the courts. Steve, Ellen, and I—and other CORE activists and students in L.A.—were eager to participate in what turned out to be one of the last organized Freedom Rides. In preparation for our journey, we went through an orientation and training in CORE’s non-violent philosophy and tactics. No matter what happened—if someone spit on you, called you names, knocked you down—you pledged not to fight back.

We knew we were putting ourselves at great risk. But we were not deterred. Riders who were under 21 had to get permission from their parents. And all of us wrote our last wills and testaments.

We left L.A.’s Union Station on August 9, 1961. When our train arrived in Houston, the 11 of us from L.A. joined seven members of the Progressive Youth Association, mostly students from Texas Southern University. Our plan was to desegregate the coffee shop at Houston’s Union Station and then continue on to Mississippi.

Our task as Freedom Riders was to sit down in places like that coffee shop—and then go to jail. The idea was to generate publicity to put pressure on lawmakers to make change. Segregationists called us “outside agitators,” which is exactly right. We did what local activists couldn’t have done without great personal risk to themselves and their families. Young people from other parts of the country (like Steve, Ellen, and me) didn’t need to worry about getting jobs—we weren’t planning to stick around. The only way to get to us was to take us into temporary custody.

It only took 45 minutes before we were arrested at the Union Station coffee shop. Local law enforcement knew a Freedom Ride was coming through and were waiting for us when we entered. Their vehicles were parked at the nearby curb. We took seats at the whites-only counter and requested service. We were refused. A police commander asked us to leave the premises. Not a single one of us moved, and he announced that we were all under arrest. We were ordered into the nearby vehicles and taken to jail. The process was smooth and efficient, much like going through an airline security check these days.

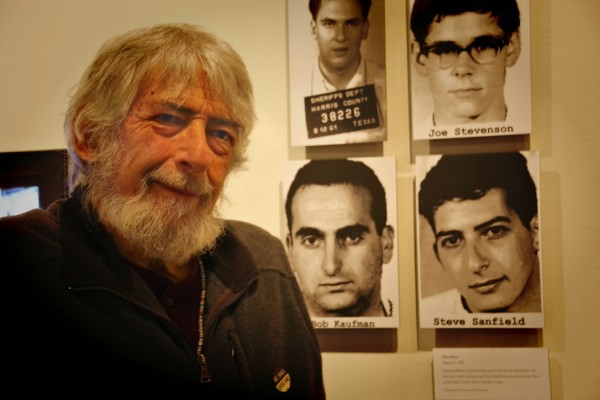

We were booked into the Harris County Jail, where we were segregated by gender and race in the jail’s general population. We black males were welcomed as heroes by the men in our tank once they found out that we were Freedom Riders. Of everyone—black and white, male and female—the white men received the worst treatment. Steve Sanfield, along with Steve McNichols and Robert Kaufman (all of whom are deceased now), and Joe Stevenson were beaten bloody by other prisoners, and carried physical and mental scars for the rest of their lives. Like many Freedom Riders, they paid a personal price to secure the right for all of us to travel without racial restrictions.

Steve Sanfield at a 2011 exhibition at the California Museum.

We spent a few weeks in jail. As soon as our lawyers visited and saw how the white riders were being abused, we were bailed out. We had our days in court and were found guilty of misdemeanor “unlawful assembly” charges. These charges were later overturned on appeal. Upon our release, I returned to Los Angeles with my fellow CORE members.

The rest is history. The violence against Freedom Riders and their incarceration got a huge amount of publicity across the U.S. and abroad. That attention, and the demands of the public, prodded President John F. Kennedy into action. In November 1961, his administration pressured the Interstate Commerce Commission to act.

And change came. The “whites only” and “colored” signs were removed from train station coffee shops and bus station restrooms. The Freedom Riders had secured an end to racial discrimination in interstate travel facilities, and freedom of movement for everyone. It was a crack in the massive scheme of segregation. I am proud to have been a part of it.

We L.A. Freedom Riders moved on with our lives. For me, that meant entering the new world of civic and electoral politics of Los Angeles, motivated by my experiences in the civil rights movement and my desire to help meet the need for a more representative government. For Ellen, it meant finishing her education and gaining employment as a social worker in California state government. For Steve, it was back to literature and a creative life as a storyteller, poet, author of children’s books, and builder of a cultural institution.

I recalled those days of August 1961 when I attended Steve Sanfield’s memorial last weekend. I thought of his courage—and the courage of every Freedom Rider—when I traveled by Greyhound, and walked through bus terminals free of the racial animus that we helped to eradicate.

Send A Letter To the Editors