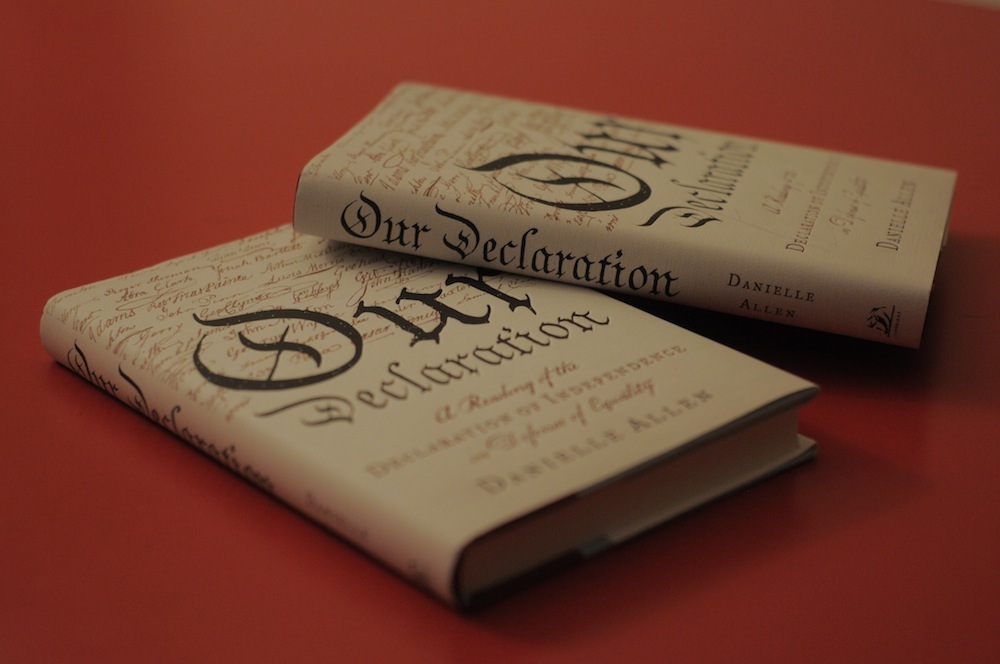

Danielle Allen, author of Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality, is the winner of the fifth annual Zócalo Book Prize. Allen’s insights into the significance of equality in America—from the 18th century to the present—make Our Declaration the 2014 nonfiction book that best enhances our understanding of the forces that strengthen or undermine community and human connection.

The Zócalo Book Prize, which is awarded in conjunction with our annual poetry prize, furthers our mission to bring people together around ideas and to get us talking about how and why we connect, and what institutions and ideals, habits and mores, allow diverse groups to cohere. By recognizing an author whose work in this field we consider exemplary, we hope to encourage other thinkers and writers to delve into one of the most important issues of our time.

Allen, a political philosopher at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, joins a distinguished roster of past winners: MIT Center for Civic Media director Ethan Zuckerman, New York University social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, London School of Economics and New York University sociologist Richard Sennett, and journalist Peter Lovenheim.

Each of our winners has viewed connection and community from a different lens. In her close reading of the Declaration of Independence, Allen asserts that the document’s primary argument is not merely about the importance of freedom, but of equality, too. Contemporary political discourse has largely cast this ideal aside, in favor of defending individual rights above all.

“Such a choice is dangerous,” writes Allen in the prologue to Our Declaration. “If we abandon equality, we lose the single bond that makes us a community, that makes us a people with the capacity to be free collectively and individually in the first place.” Our Declaration explores the importance Thomas Jefferson and his contemporaries placed on equality and community, and how, in just 1,337 words, they forged a document with the power to build a cohesive and united nation.

As the winner of the Zócalo Book Prize, Allen will receive $5,000—and on Friday, April 24, she’ll deliver a lecture: “Can Democracy Exist Without Equality?” at MOCA Grand Avenue. Please see more details on the award ceremony here.

We asked Allen a few questions about the themes of Our Declaration, and the state of equality and community in America today:

Q. How does our belief in equality bind Americans together?

A. Equality is fundamental to forming the social bond of democracy. If we don’t achieve equality among us, you see the citizenry—the people of the country—split up into factions. You need equality just to build a basis for solving hard problems together. Our commitment to equality has weakened considerably for the past few decades, which is one of the causes of greater social strife and tension in America today.

Q. How can the Declaration of Independence help us deal with questions and issues surrounding a lack of equality in America right now?

A. The Declaration makes a really powerful argument for why we all have a right to participate in politics and contribute to our collective decisions. It sets a really high bar for what a democracy needs to achieve. A democracy needs to give people equality as well as access to government as a tool we can use collectively to ensure our safety and happiness. The Declaration can educate us about how to think about our aspirations for equality. Our muscles for thinking about liberty are incredibly strong; ideas about freedom trip off our tongues. We no longer have ideas that trip off our tongues about equality. I’m trying to rebuild and revive a basic understanding of why equality matters and what it consists of.

Q. If equality and freedom aren’t in opposition, what is a more productive way of viewing their relationship?

A. Any time somebody evokes the concept equality, you have to ask them to define it. Are you talking about political equality, social equality, economics, moral equality? Equality and freedom always have belonged together. You can’t have freedom unless everybody is free, and you can only have that if nobody is dominating everyone else. If some people are free and dominating others, you don’t have freedom, because the people who are dominated are not free.

Economic issues are a lot harder to think about than they were in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, before industrialization hit. In the wake of industrialization, we’ve lost sight of how to think about equality and economic issues. You can resolve a lot of questions about economic inequality by asking what economic policies do the most to achieve political equality among the citizenry.

Q. What line or lines from the Declaration of Independence do you wish today’s politicians would read more closely or consider more thoughtfully?

A. For me it’s not just about politicians. It’s about all of us. The line I wish all citizens—all members of our polity, including politicians—would consider more carefully, is the concluding clause of the famous second sentence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident … That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

The message is that every generation has a responsibility to consider how our government is working for us. Are our institutions and principles securing our safety and happiness? If not, how can we fix them?

Q. What would the Founding Fathers think about the state of community in America today?

A. I think they’d be really dismayed. One of the things that characterized the revolutionary period was a real openness of participation at all social levels in thinking about public questions. So, for example, as the Founders were trying to figure out what they thought was wrong with King George’s administration, from Georgia to Massachusetts, they had to put posters up saying, “Everybody meet in Farmer Smith’s field on Sunday to talk about what your view is and what you think is wrong.” There was a really strong participatory element in those early revolutionary days which we’ve walked away from, and which I hope we can recover.

Send A Letter To the Editors