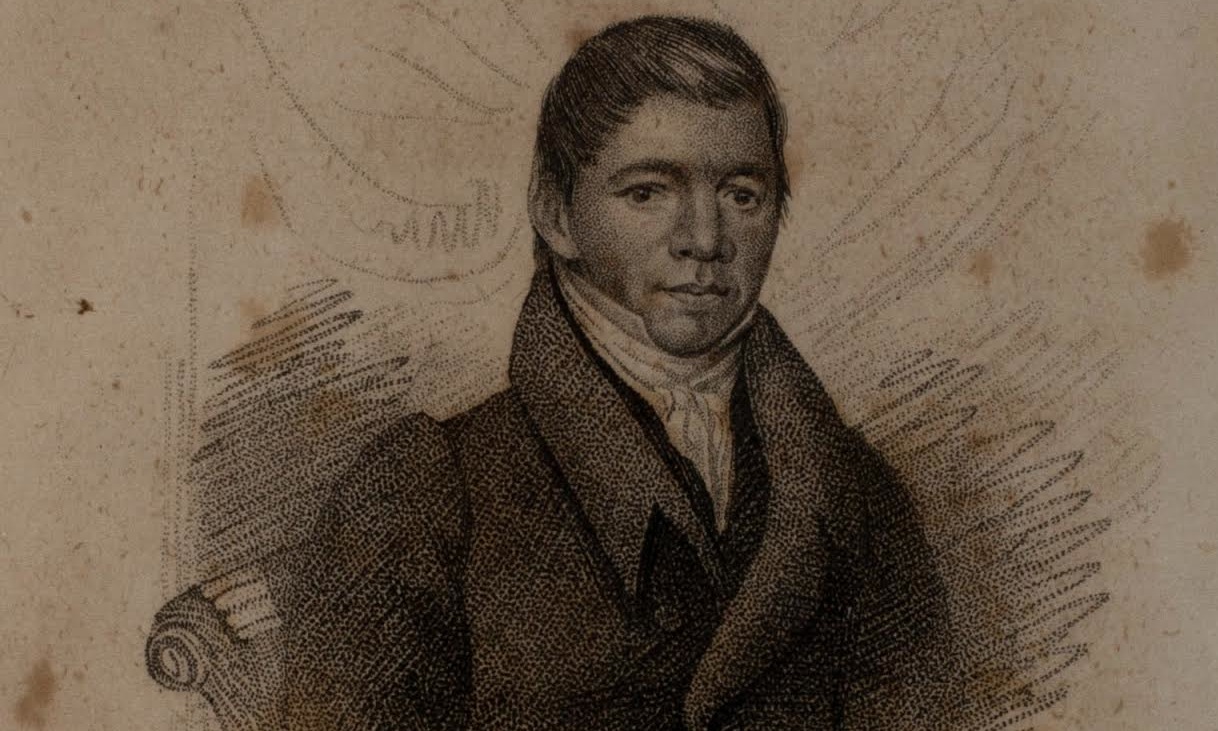

On April 1, 1839, a New York City medical examiner performed an autopsy on a man at a boardinghouse in a working-class neighborhood of lower Manhattan. He had performed scores of such examinations each month, but this one was especially significant though he did not recognize the person: 41-year-old William Apess had written more than any Native American writer before the 20th century, and had attained fame and notoriety in his short life for championing native peoples’ rights.

Still largely forgotten except by those who work in Native American studies, Apess deserves the same widespread recognition as others in the antebellum period who questioned the sincerity of the nation’s commitment to democracy. He was a leading light in a generation of reformers that included Margaret Fuller and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, champions of women’s rights; Frances Wright and Orestes Brownson, fighters for the dignity of labor; and William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, David Walker, and Frederick Douglass, advocates for African-American freedom and equality: voices unafraid to speak the truth about the emperor’s new clothes. In the 1820s and 1830s, Apess stood both with these critics yet, as a Native American, apart from them, his voice raised in protest against the plight of indigenous peoples, whom all too many white Americans wanted to believe were doomed to extinction.

No one could have predicted Apess’ meteoric rise. He was born in abject poverty in 1798 in rural Massachusetts, of “colored”—which at that time could mean mixed-race—parents who moved to Connecticut a few years later only to separate. He then lived with his grandmother but found little stability. She beat Apess so severely that the town’s overseers of the poor stepped in to place him with various white families before formally binding him out as an indentured servant.

His life changed, however, when he experienced a powerful conversion to Christianity as a result of Methodist preaching. Assuming control of his life for the first time, he escaped his indenture during the War of 1812 and enlisted among New York troops. Still only a teenager, he saw action in several battles around Lake Champlain and in expeditions against Quebec. At the end of the war, Apess spent time among Native American tribes in northern New York and eastern Ontario. When he returned to Connecticut months later, he formalized his commitment to Methodism through baptism and began to work as a preacher, often among mixed-race congregations.

In 1825, the Methodist leadership assigned Apess to a circuit throughout New England and New York. More and more confident in his self-expression, four years later he published A Son of the Forest, a spiritual autobiography that related the story of his life to date. He also preached and lectured in Boston, and came to the attention of prominent reformers like the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Apess also continued to publish, in 1833 both a sermon and the book Experiences of the Five Christian Indians; or, A Looking Glass for the White Man, in which he condemned the prejudice victimizing Native Americans.

That year, when the nation was increasingly exercised over the seizure of Cherokee lands and the tribe’s forced removal west of the Mississippi River, Apess also visited a Native American congregation on Cape Cod that was fighting on a smaller scale the same battles as the Cherokee, against usurpation of its tribal rights and privileges. Apess came to lead the Mashpee’s fight to regain control of tribal lands that white overseers were pilfering. He vociferously argued the tribe’s case for more self-government to the state legislature, and subsequently was arrested and jailed for several months for his part in what became known as the “Mashpee Revolt.” He published an account of this struggle in his 1835 book Indian Nullification of the Unconstitutional Laws of Massachusetts, whose title sought to play off contemporary debates over the right of state nullification of national laws.

After the Mashpee won the right to self-government, Apess returned to Boston. In 1836, he delivered his remarkable “Eulogy on King Philip,” in which he proclaimed the 17th-century New England Indian leader during King Philip’s War (which lasted from 1675 to 1676) as great a patriot as George Washington. By request, Apess repeated the speech in other New England cities. “O Christians,” Apess challenged, “can you answer for those beings that have been destroyed by your hostilities, and beings too that lie as endeared to God as yourselves, his Son being their Savior as well as yours, and alike to all men,” whatever their color? In its call for white Christians to acknowledge that God embraces people of all colors and its recasting of New England history to appreciate Native Americans’ bravery, the “Eulogy” stands with Frederick Douglass’ “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” as one of the most searching indictments of the nation’s institutional racism. This address marked Apess’ full emergence as a public intellectual.

But Apess’ luck then turned. He became embroiled in lawsuits on Cape Cod and had his goods attached for debt. To escape this turmoil, he moved to New York, where he appeared in the city’s lecture halls and began a career as a speaker on Native American history and culture. Unfortunately, in a crowded boardinghouse on Washington Street, a lifetime of hardship caught up with him.

William Apess was an extraordinary man. He was not some sport or relic—another example of the nation’s vanishing “Indians”—but someone who strove to understand himself as a member of an indigenous nation within the United States of America and so to claim for himself, his tribe, and native peoples in general their rightful acknowledgement by the new nation. The magnitude of his legacy has only recently become clear. As Native American activist and intellectual Robert Warrior puts it: “Apess is the Native writer before the 20th century who most demands the attention of contemporary Native intellectuals.” And, I should add, the attention of contemporary Americans.

For over two centuries, white Americans’ self-righteous belief in their divine mission and the nation’s “manifest destiny” informed their harsh treatment and virtual extermination of indigenous peoples. Apess challenged this myth, and, therefore, became one of the nation’s great prophetic voices. He deserves our attention, as a reminder that the United States is still in the process of becoming, not as another speechless monument.

Finally, we must not insult his heritage by terming him simply a great “American.” First and foremost, he was a son of the forest—William Apess, Pequot, lived in a place that was called “America” only by those with a very different relation to this land and its indigenous peoples.

Send A Letter To the Editors