How do you make Salinas a more peaceful, safer community?

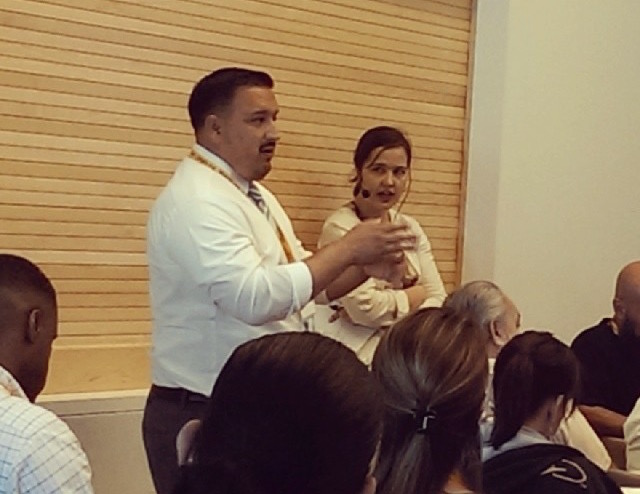

Trying to help people in this community figure that out is my job. Or jobs. I double as the community safety administrator for the city of Salinas and director of the Community Alliance for Safety and Peace, or CASP.

That may sound like just another acronym, but forming CASP has been a big part of a very important advance in addressing violence in Salinas. CASP is a coalition of more than 60 agencies that have worked close together for the last seven years—we have two meetings every month—to make Salinas safer. The work has been complicated, but that’s only because the problem of persistent violence here is itself complicated.

Even after working on the problem for so many years, I still ask myself: Why does a city that’s so naturally beautiful and filled with the charismatic charm of good, hard-working people struggle with such poverty, low literacy rates, and high rates of violence? The answers lie in the history and current context of our population of 155,000. The agriculture industry here, powered by the low-cost labor of thousands of mostly Mexican immigrants, produces about 70 percent of the lettuce consumed in the United States, along with hundreds of other crops, wine grapes, and flowers.

Today, Latinos make up 75 percent of the population, yet often say they feel starved of influence in government, business, and education. This lack of representation leads to complaints of racism and unequal treatment. Even with the lucrative industry here, 21 percent of our population lives below the poverty line; in East Salinas, that number jumps to 36 percent. And poverty is a condition in which gangs and violence thrive.

Youth violence is a problem in every American city, but our youth homicide rate per 100,000 residents is the highest in California (and has been so for three of the last four years). Starting in the early ’90s, the primary response by law enforcement in Salinas was to conduct major gang sweeps that targeted gang leadership and the most violent offenders. Though this tactic does quiet the streets for short periods of time, the effect is not lasting. History shows us that the problem returns—because the violence is a symptom, not a root cause. Poverty, drug use, low literacy rates, and access to firearms need to be addressed.

Our small city has dealt with big-city violence for a long time. In early 2009, two groups seeking to address the problem—the Community Safety Alliance, formed the previous year in Salinas, and Violence Prevention Committee, formed by the Monterey County Children’s Council—joined forces under the name CASP. The goal was to build a coalition of everyone—top city and county leaders, including the chief of police, district attorney, chief of probation, juvenile court judge, county office of education, county director of behavioral health, county director of social services, local school superintendents, and non-profit executive directors. We found state partners (as founders of the California Cities Violence Prevention Network) and federal ones (as one of the original six cities in the White House’s National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention). Other cities—San Jose, Boston, and Memphis—have had success with similar coalitions as the basis for sharing best practices and technical assistance on public safety questions.

I agreed to come on board after a career as a school principal and charter school founder because the approach reflected my experience in youth development. I also saw the lives of members of my immediate and extended families being affected by the violence and terror associated with gang culture—and by the unjust treatment they received in the education and juvenile justice systems. As early as kindergarten, my younger brother and a few male cousins were labeled as traviesos (troublemakers) by both our family and staff at their schools.

I saw firsthand how these relatives were tracked into getting involved in gangs by the very adults who were supposed to support their growth. It’s not to say that they didn’t have choices, but they were presented with fewer opportunities and harsher consequences than most of their peers. The way in which school administrative staff chose to discipline and describe these young men to their families had a lasting impact on their self-confidence and future choices. I strongly believe that a different approach might have laid a more positive path back then for my brother and boys like him.

Salinas was one of the first cities in California to develop a strategic plan on violence reduction. Our plan has specific short- and long-term goals, six focus areas identified by the community itself, and a four-part strategy that relies on connecting with community and using data.

The city of Salinas has created and funded a division to support CASP, and youth violence has been declared a top priority by both leaders all over the city and county. In addition to our regular meetings, we have a team that focuses on the Hebbron Heights neighborhood for East Salinas that includes our coalition’s professionals, community leaders, and two Salinas police officers. These officers and school counselors refer to CASP young people who may be at risk of being a victim or perpetuator of violence. We reach out to the young person’s family with resources, including mental health services, housing, alternative educational opportunities, youth development programs, physical health services, and food.

A significant component of our plan is an effort to develop leaders in the Salinas community with our Community Leadership Academy program for adults and our Summer Youth Academy program. So far, the Community Leadership Academy—which is offered in Spanish and English—has trained more than 75 leaders in tools and strategies for civic engagement, community organizing, and grant writing.

Alumni from this group have formed a committee at CASP and are now represented on our executive committee and general assembly. Graduates also develop community-impact projects. One graduate, who completed the course with her husband and eldest daughter, focused on school engagement, establishing and leading a large and active Spanish-speaking parent group at El Sausal Middle School. The group created patrols to monitor parking lots and street crossings before and after school.

Our work to make Salinas a more peaceful city is far from complete, but we have made progress. The rate of violent crimes involving young people has steadily dropped over the last five years, and last fall, statistics showed that violent crimes against Salinas youth had reached a 15-year low. And we are still planting the seeds of violence prevention that will allow us to sow the harvest of peace in future seasons.

Send A Letter To the Editors