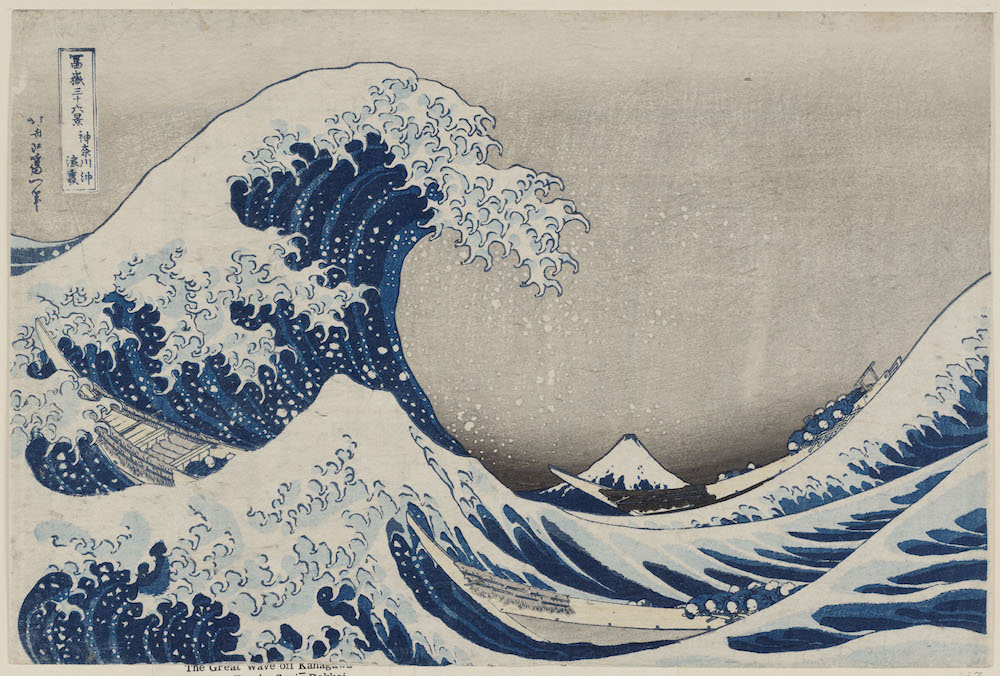

Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa-oki nami-ura), also known as the Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjûrokkei) Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760–1849) about 1830–31 (Tenpô 1–2) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper * William Sturgis Bigelow Collection * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In the aftermath of the horrific 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku, Japan, a well-known image of a single cresting wave popped up everywhere, from relief fundraising appeals to the work of Japanese artists who adapted it to comment on the disaster. The 1831 woodblock print, “Under the Wave off Kanagawa,” depicts a swell of water that appears to engulf not only the boatmen delivering fresh fish to the city of Edo (known today as Tokyo), but even Mount Fuji.

Since its creation 184 years ago, Katsushika Hokusai’s work, also known as the “Great Wave,” has been mobilized as a symbol of not just tsunamis, but hurricanes and plane crashes into the sea. It is precisely because “Under the Wave off Kanagawa” has lent itself to so many reinterpretations that it has become a global icon, as instantly recognizable as a film or music celebrity. An impression of the print is currently on view in “Hokusai,” an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Waves are unpredictable. One minute they’re there and the next they’re gone—and we experience them only in the process of their disappearance. Hokusai had an uncanny ability to capture waves in all their variety, and returned to the subject again and again over the course of a career spanning six decades, from the 1790s until his death, in 1849. He made many variations of the drama of man and nature evoked in the “The Great Wave.” Hokusai also created scenic views of waves breaking on a beach, designed waves to decorate combs and the transoms used in architectural interiors, and wrote instructional manuals for aspiring artists on how to paint incoming and outgoing waves. In one woodblock printed book illustration, a magician conjures up a wave in the palm of his hand. In each of these, it is the sense of arrested movement that makes the wave come alive.

“Express Delivery Boats Rowing through Waves,” Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

The “Great Wave” is set off the coast of the Bōsō Peninsula, a region notorious for its rough seas. It’s a startling and playfully subversive juxtaposition—this wave caught in arrested motion that improbably steals the stage from the sacred volcano of Mt. Fuji. But, despite its topographical specificity, Hokusai’s print is a work of imagination open to interpretation. There is no historical evidence specifically linking this artistic vision to a tidal wave.

And yet the “Great Wave”—along with its role as a symbol of disaster—is often linked to actual tsunami. This link is sometimes indirect, as when the image was used to discuss the one that occurred in 2011, and sometimes direct—as in claims in a recent article in the Economist that Hokusai was depicting the tsunami of 1700 in his woodblock print.

After a devastating earthquake in January 1995 in Kobe, Japan, Nature magazine featured a detail of the print on its cover to accompany an article about the discovery of geological evidence that an earthquake in the Cascadia region of Oregon and Washington caused the 1700 tsunami in Japan. Nature acknowledged its mistake by publishing letters to the editor drawing attention to the historical inaccuracy being promoted.

Japanese historians have long resisted this interpretation because Hokusai’s design is a work of the imagination and there is no evidence that he envisioned a tidal wave. After the Japan tsunami in 2011, they took to radio and television in the UK to insist that Hokusai’s portrait was not of a tidal wave. The wave was, they said, wind-driven. Scientists concur, arguing that this iconic image should be read as a “plunging breaker” or a “rogue wave,” a freak occurrence caused by high winds and strong currents in the open sea rather than on the shore.

The perception that the “Great Wave” is a tsunami seems to be the consequence of translation, mistranslation, and association that has occurred since the image first circulated outside of Japan. For the late 19th-century French avant-garde, Hokusai’s work became emblematic of the Japanese influence—seen in the work of Monet and Van Gogh—that swept away the academy’s tired values, though many also saw these new artistic styles as threatening to traditional French culture. This disruption was widely characterized as “La Nouvelle Vague,” the New Wave.

The conflation of Hokusai’s wave with a tidal wave may have been helped along by the fact that the fashion for all things Japanese in Europe and America in the late 19th century coincided with an 1896 tsunami that caused massive destruction in northern Japan. Reported worldwide, it brought home to Europeans and Americans the dangers of a natural disaster previously known only at a distance. While photographs testified to the damage and loss of life the tsunami caused on land, they could not capture the wave itself, leaving its appearance up to the viewer’s imagination. The “Great Wave” filled in that missing piece.

Then there’s the ways in which the image has been used as a stand-in for a wide range of disasters. In 1948, novelist Pearl Buck wrote a moving, allegorical children’s story set in Japan titled The Big Wave that was illustrated with Hokusai’s print. It was intended to help children deal with the aftermath of World War II and the beginning of the Atomic Age.

Memorial to Panam Flight 800 in Stoney Point Beach, Long Island

The aestheticizing distance of Hokusai’s cresting wave continues to provide an alternative to the horrifying realities of the global impact of volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and tsunami in the Pacific region, as well as other man-made disasters. The artist David Salle incorporated it into a pictorial cycle that comments on Hurricane Katrina, and a memorial in Stoney Point Beach, Long Island, to the victims of Pan Am Flight 800—which crashed over Long Island in 1996—features an image of Hokusai’s wave morphing into birds flying skyward.

Easily adaptable, the “Great Wave” has taken on many contradictory meanings that were likely never imagined or intended by its creator. But rather than seeing this as a case of “lost in translation,” for me this potential for pluralism is precisely what makes the “The Great Wave” great.

Send A Letter To the Editors