How big is the gap between all the rhetoric about the value of employing people with autism and other brain-wiring differences and the realities of the job market?

You can get answers to that question by visiting the central San Jose offices of EXPANDability, an agency serving workers with disabilities in Silicon Valley. When I visited this summer, several employment projects were in full swing.

In the large computer lab, jobseekers searched Internet job boards and submitted applications. In a nearby classroom, 12 deaf young adults attended a life-skills class. Near them, EXPANDability’s staffing director, Priscilla Azcueta, interviewed candidates for temporary administrative positions at a local university. In another office, EXPANDability Executive Director Maria Nicholacoudis oversaw the “Autism at Work” program, in conjunction with SAP, the international software giant. She is trying to replicate it with other employers.

Like other local employment agencies serving adults with disabilities, EXPANDability’s population has shifted considerably in the past decade from individuals with physical disabilities to a larger percentage of individuals with neurological conditions, including autism, dyslexia, ADHD and other brain-wiring differences. As a result, EXPANDability has become part of the “neurodiversity” movement in Silicon Valley and throughout California.

I first learned of this movement in the early 2000s, when I was director of California’s labor department. Part of the department’s mission involved finding jobs for the population of workers referred to as “workers with disabilities.” Neurodiversity, which contends neurological differences are normal and should be accommodated in the same way gender and ethnic differences are, was a budding movement; its growth in the past few years has been rapid and striking. There are now neurodiversity conferences, neurodiversity books, and neurodiversity professionals. In June, an overflow crowd of over 150 persons from throughout Silicon Valley gathered at the Microsoft campus in Mountain View for a “Neurodiversity in the High-Tech Workforce” conference. Researchers praised the competitive advantages for tech enterprises of employing adults with dyslexia (problem solvers, creative visual thinkers), as well as adults with autism (attention to detail, ability to concentrate).

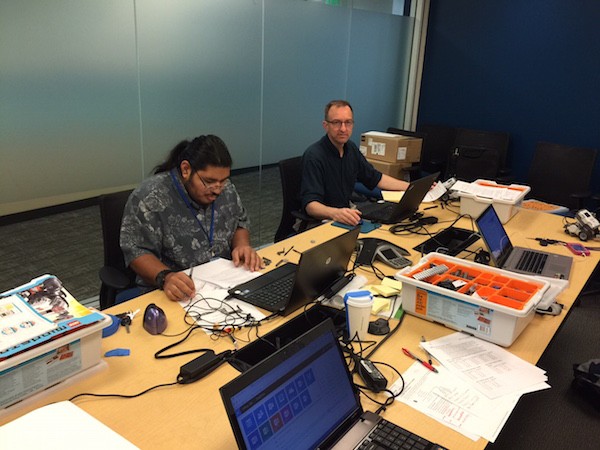

EXPANDability workers build robots.

Mark Jessen, an EXPANDability participant with autism who is in his early 50s, could be on the poster of the neurodiversity movement. Jessen is largely self-taught in the information technology field; he spent some time after high school at a community college, but left without a degree when he discovered IT. For over a decade, Jessen was a partner in a small information technology venture, in which he handled the technical duties and his partner did the marketing. But when his partner passed away in 2010, Jessen was unable to carry on the venture. For over three years, he couldn’t find a job.

Through the volunteer adult autism group AASCEND, he was introduced to EXPANDAbility and its Autism at Work program. SAP recognized his unusual computer engineering skills and he recently was hired as a network engineer at SAP’s Palo Alto office. EXPANDability located other local adults with autism who had been unemployed for some time, and based on their technical skills they too have been hired by SAP. “Every day at SAP is a good day for me,” Jessen says after so much time without a steady job.

SAP, companywide, has become a champion of neurodiversity, committing to at least one percent of its worldwide workforce being adults with autism by the year 2020 (roughly 650 positions by its 2013 workforce). The SAP efforts are helping to push other tech companies to adopt Autism at Work, including Microsoft. EXPANDability is now recruiting adults with autism for employment in Microsoft’s Redmond offices.

This is the promise of neurodiversity; but EXPANDability’s experiences also show the gap between theory and practice that remains. Though the SAP Autism at Work program has achieved national and international press, the numbers of participants remains modest in each location. The first SAP cycle in 2014 involved nine trainees in the Bay Area, of whom seven were hired. The second cycle also involves nine trainees, of whom six are currently hired. The Microsoft Autism at Work program is starting with 10 participants.

Additionally, each placement usually requires considerable effort. Even with Jessen’s computer skills, his placement was far from smooth. It took over 400 days from the time of his first contact with SAP until he received an offer letter. During this time, he went through a lengthy battery of assessments, was shifted from a software role to one in network engineering, and waited on several reorganizations with SAP. It was mainly the persistence on the part of Jessen and the SAP Autism at Work coordinator, Jose Velasco, that resulted in his placement.

EXPANDability Executive Director Nicholacoudis is active in speaking statewide, spreading an upbeat message that neurological conditions long regarded as “disabilities” are more accurately seen as competitive advantages. But Nicholacoudis also acknowledges that today most placements are slow and difficult. In theory, EXPANDability seeks to tailor the job around the neurodiverse job seeker’s individual passions and skills. But passion and expertise are not easily translated into a specific job open at a particular time in a particular area.

Many of EXPANDability’s neurodiverse clients do not easily fit into a company structure and workplace rules. Some have issues with hoarding paper or food, and do so in their work stations; others have personal hygiene issues, or can’t seem to get to the job site or come back from breaks on time. “Placement is the first step of employment, and often the easiest one,” Nicholacoudis says. “That’s why we give a great deal of attention to retention after placement, to job coaching and supports, and to getting buy-in from throughout the company.” Providing support at the work site is labor-intensive and costly—especially the job coaches who can facilitate a transition period.

EXPANDability is constantly looking at new placement strategies for its neurodiverse clients. In recent years it has added a staffing company that allows employers to take on workers on a temporary basis, and evaluate their performances. “The staffing approach enables our workers to get in the door, which is the chief challenge in employment today, and show what they can do, and how their positive attitudes can improve the workplace,” says Azcueta, the staffing company director. One of her recent placements was an administrative assistant at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “The university had hesitations at first, but liked him so much it has led to a permanent position.”

A lively online community of autism employment practitioners and parents has grown up on sites like Autism Employment Network by Autism Speaks, Autism Innovators, and Spectrum Employment Network. We share articles with such titles as “What skills do people with autism have?”, “Where to Find an Untapped Tech Workforce: Ask Temple Grandin,” and “Self Employment for Persons with Disabilities.” The articles and comments are almost all positive, and are full of ideas for autism employment. But the number of companies actually hiring and embracing a corporate culture of neurodiversity remains small.

Send A Letter To the Editors