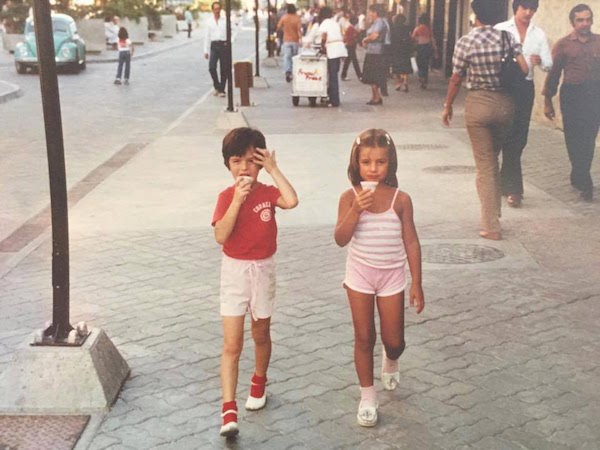

Growing up in my hometown of Caracas, I wanted nothing more than to be seen as a sifrina. To be, in Venezuelan slang, counted among the rich kids—a spoiled, fashionable city girl with money to waste and expensive American tastes.

But commuting for hours from my single mother’s modest apartment on the outskirts of the city to the upscale neighborhood of my private school, I often felt inadequate.

We came from a decidedly middle-class family. We had access to food, health care, and subsidized housing. We enjoyed road trips to the beach in the summer. We had the means for me to spend weekends at the city’s biggest mall, the sprawling Centro Ciudad Commercial Tamanaco, wasting time in its hundreds of stores and dining at Burger King with my friends. We could afford (though barely) to send me to a place where I could get a good education.

Nevertheless, at my elite private school filled with the conspicuous consumption of sifrinos and sifrinas, I was ashamed that I owned only one pair of trendy imported jeans. This was my world at the time: Growing up in Caracas in the 1980s meant that your money and personal connections—or lack thereof—could easily consume you. Even as a teen.

Never mind that my mother worked very hard to pay for my private school, to get food on our table, and to take us to the beach a few times a year. We had a steady home filled with our belongings: the same plants and couch from my entire childhood; the black-and-white photos my grandmother had left behind. But all I could think at the time was that I wasn’t spending summers in Miami like my other schoolmates, shopping till I dropped. In those days, my country was known as “Venezuela Saudita” (Saudi Venezuela) and my family clearly wasn’t cashing in.

Life went on for me in this kind of pretense for a few years. Then El Caracazo arrived.

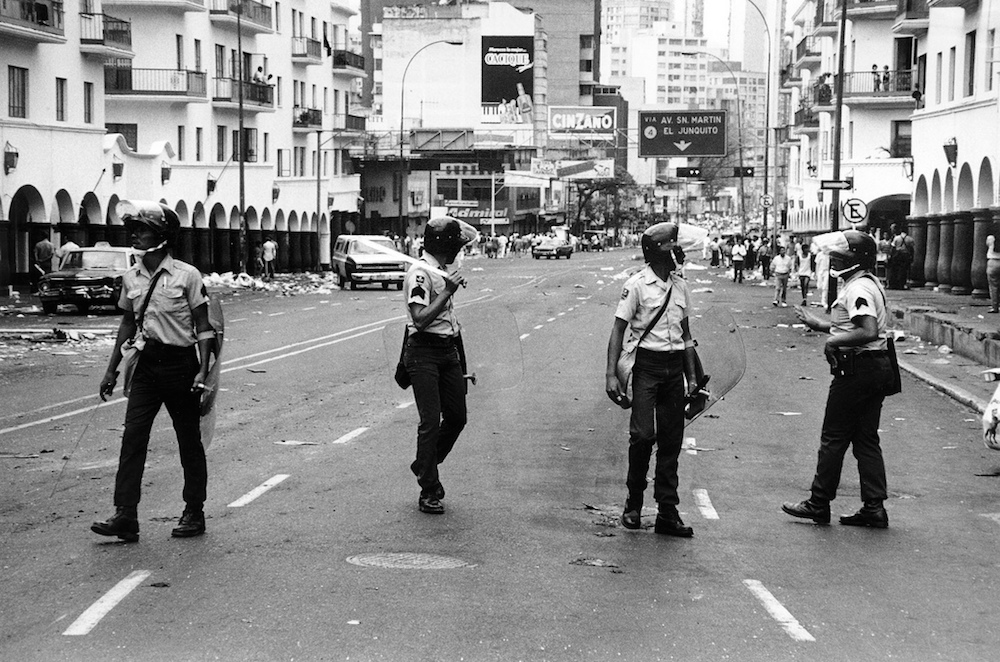

El Caracazo, or El Sacudón, “the big shake-up,” started as street protests against government reforms that raised the price of gas and public transportation, but quickly erupted into an insurrection threatening to topple the neoliberal government of Carlos Andrés Pérez.

We were glued to the TV news as the unrest paralyzed our city with riots, shootings, and hundreds—some estimate thousands—of extrajudicial killings, most at the hands of security forces. Horror washed over us as we saw footage of dead bodies strewn on downtown streets and the empty shelves of looted stores. Shock overwhelmed us as we read newspaper headlines like “Mata el Hambre con Comida de Perros!” (“She Kills Her Hunger with Dog Food!”) that described a mother of seven who had resorted to feeding her family kibble amid the chaos.

Although my friends and I were too young and naïve to understand the real reasons behind El Caracazo at the time, I understand now that it was triggered by economic desperation—real desperation. An estimated half of Caracas’ residents were living in extreme poverty. But I had failed to see the despair that provoked impoverished men and women to take to the streets and risk their lives to face a brutally repressive regime. In my teenage obsession with stylish jeans and the Americanized CCCT shopping mall, I had been blind to how delusional my feeling of inadequacy was compared to the way most people in Venezuela lived.

The demonstrations lasted for a little over a week, but El Caracazo did not end. Political instability radiated beyond Caracas over the next year. Coup d’état atttempts followed, led by an idealistic military officer from working-class roots named Hugo Chávez. The country’s foreign debt mushroomed. Corruption charges plagued President Pérez and eventually forced him from office.

El Caracazo would go on to trigger a new world order. It would go on living inside all of us. And, it would push many to leave—including my mother and me.

In August of 1990, a few months after I’d turned 14, my mom and I gave our furniture away and stowed some boxes inside a friend’s house. We packed only a couple of suitcases with a few important things. A couple of nights before our one-way flight out of Caracas, my friends threw a party for me and we drank cuba libres—rum and Cokes—until I couldn’t see straight anymore. I cried for most of the night, wallowing in my drunkenness, fearing I would never see my friends again. Yet I also reveled in the thought that I was one of the first of my crew to leave, heading to the home of our teenage infatuations: the United States.

My first year in the U.S. was dreadful. In the suburban New Jersey town where my mom and I landed, I couldn’t find my way around, literally or figuratively. The quiet tree-lined streets, the orderly traffic, the friendly school crossing guard who mispronounced my name, the unthinkable assortment of sugary cereals in the supermarket—it all annoyed me in its civilized neatness. I missed Caracas, with its urban, sprawling chaos. There is something about home (or, perhaps, our colored memory of it) that is always comforting. Even if that home is rife with criminality and social inequality.

But after a year, just as I was ready to give up, things started clicking. Seemingly overnight, I was able to form coherent English sentences and carry on conversations. I became focused on sounding American—nothing made me happier than strangers telling me they couldn’t tell I had a “Hispanic” accent—and I insisted that my mother speak to me in English when we were in public. Now that I was surrounded by other public high school students whose parents lived in low-income apartments and drove beat-up cars, I could focus on being cool—indulging my rebelliousness, staying out until late at night—rather than on attaining social or economic status. I blossomed into an all-American teenager. The disparities in my world had shrunk to a more manageable size.

And as time went on, my idea of home started shifting as well. This is the sad reality of immigrants everywhere: The longer we stay in the new country, the more distant our old homes become. We are often overcome by nostalgia, taken, as Brazilians so eloquently describe, by saudade: “the love that remains.” Yet we hold out hope that the new place will one day truly become ours.

I eventually returned to Caracas a few times in the 1990s and 2000s. Each visit, I found a place less and less recognizable. In the time I was gone, Hugo Chávez, that charismatic military officer, had gone from coup leader to prisoner to president.

The violence and the poverty persisted, amidst the Chavista revolutionary hyperbole. Many of my old friends and neighbors, like hundreds of thousands of other Venezuelans during that time, had gone or were about to leave, driven by the deteriorating economy and the growing crime. Chiqui ventured to Spain. Lucía ran off to Colombia. Diego and Maya escaped to the U.S.

It’s been seven years since I last visited Venezuela, and only one of my school friends, Carolina, remains in the city of our childhood. She wrote to me recently and said that she wants to stay in her beautiful country, but that her family constantly thinks about leaving.

I now live in Ecuador, which has been boiling over with political unrest and street protests and yet—in a somewhat funny coincidence—welcoming an unprecedented number of immigrants from Venezuela. Not a day passes here where I don’t meet a fellow Venezuelan. Their stories are like mine—migrants leaving with just a few belongings, starting over in a new place. A few months ago, I met a 30-year-old electrician from Catia, one of Caracas’ slums. He had been working hard and had finally saved the money to bring his wife and sons from Venezuela. After reuniting with them, he told me, he has no intention of going back. “I never thought I’d say this,” he said, “but in just a few months, I can say that Ecuador is fast becoming home.”

I understand where he’s coming from, as I have developed a more elastic understanding of what that term means. I’ve bounced around a lot in the last few decades, stopping for a spell in places like New York City, San Francisco, Austin, Boston, La Paz, and San Diego. I’ve recognized that I am always looking for an escape route—to know, much like my mother did in 1990, that I can pack my bags and move to a better place. Today, my husband and I consider home anywhere we can find peace for us and our child. But if I am ever to find that everlasting peace in a single place, someday, I hope it ends up being back in Caracas.

Send A Letter To the Editors