Alexander and the Niece of Artaxerxes III; Master of the Jardin de vertueuse consolation and assistant, Flemish, active 3rd quarter of 15th century; Lille (written), France, Europe; about 1470 – 1475; Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink on parchment; Leaf: 43.2 x 33 cm (17 x 13 in.); 83.MR.178.123

When most people think of a medieval feast, they envision a room filled with boisterous guests and the lusty consumption of hunks of meat and goblets filled with wine. Feasts certainly performed a key social function in aristocratic households, and in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, some of these feasts were quite splendid and impressive. Artists delighted in illustrating such scenes, often with a remarkably minute level of detail. They depicted each plate, glass, and utensil carefully arranged among dishes filled with bread, fish, meat, and pitchers of wine. In these paintings, wealthy individuals sit in their finest dress at grand tables as multiple servers buzz around to bring them course after course.

When most people think of a medieval feast, they envision a room filled with boisterous guests and the lusty consumption of hunks of meat and goblets filled with wine. Feasts certainly performed a key social function in aristocratic households, and in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, some of these feasts were quite splendid and impressive. Artists delighted in illustrating such scenes, often with a remarkably minute level of detail. They depicted each plate, glass, and utensil carefully arranged among dishes filled with bread, fish, meat, and pitchers of wine. In these paintings, wealthy individuals sit in their finest dress at grand tables as multiple servers buzz around to bring them course after course.

Even today, we interpret these vibrant images as celebrations of eating and drinking in a time when food was sometimes scarce for the poor and part of a conspicuous display of wealth and bounty for the upper classes. But amidst all the pageantry and spectacle, it is easy to overlook that something is amiss: Nobody’s eating.

Medieval people had what one might call an uncomfortable relationship with food. Of course sustenance was both essential for survival and a source of pleasure. But when allowed to run wild, pleasure could lead to sin. Overindulging in food and drink trod dangerously close to gluttony, one of the seven deadly sins prohibited by the Church beginning around the 4th century A.D.

I first considered this uneasy balance after my colleague Amy Neff, a professor at the University of Tennessee, pointed it out. A few years ago, she was preparing a fascinating study of images of the biblical story of the Wedding at Cana, in which Christ miraculously transforms jugs of water into fine wine. In image after image, she started to notice a pattern: None of the attendees are ever shown drinking it. Even the steward who samples the vintage and pronounces it superior to wine served earlier in the meal doesn’t actually take a sip.

As I prepared for the exhibition currently on view at the Getty Museum, “Eat, Drink, and Be Merry: Food in Medieval and Renaissance,” and gathered manuscripts from the Getty’s collection and from a private collection depicting the consumption of food, each and every feasting image supported this observation. Take a look:

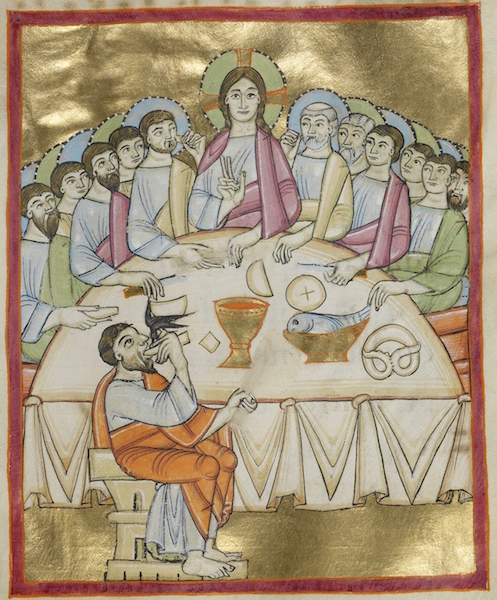

Last Supper, Benedictional, Regensburg, about 1030-40, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig VII 1, fol. 38

In the earliest manuscript in the exhibition, a 1,000-year-old book of prayers from Regensburg, Germany, has a striking Last Supper scene. At a semicircular table, Christ sits with his apostles and blesses them. Some of his followers pick up knives to eat bread, fish, and, yes, even a pretzel, laid out on the table before them. The two figures closest to Christ raise food to their mouths, but do not actually consume it. Only one apostle ingests the bread—Christ’s betrayer, Judas, who’s seated alone on the side of the table closest to us. In the biblical text, Christ identifies the rogue apostle by his act of consuming food: “Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me, one who is eating with me” (Mark 14:18). The sinister black bird that emerges from Judas’s mouth in the image marks not only his sinful act of betrayal, but also his solo consumption of food.

Temperate and the Intemperate, Master of the Dresden Prayer Book, miniature from Valerius Maximus, The Memorable Deeds and Sayings of the Romans, Bruges, about 1470-80, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 43, recto

Valerius Maximus, the author of The Memorable Deeds and Sayings of the Romans (circa 30 A.D.), appears at far left in blue conversing with the emperor Tiberius. He gestures to two groups of diners, one staid and one rowdy, discussing good and bad behavior of the temperate and the intemperate, respectively. The well-dressed nobility sit in an orderly fashion at the dining table elevated in the back of the room and placed before a luxurious textile cloth of honor. Items on the table are carefully arranged, and each individual sits in his or her proper place. In the foreground, dressed in coarse clothes, the lower-class figures signal the server for more drinks, sleep at the table, and fall off the bench onto the floor. Crumbs and an overturned cup litter the rumpled tablecloth.

Valerius never mentions feasting in his writing, and his text pre-dates the Christian Church and its warnings against gluttony, but the artist responsible for illustrating this 15th-century copy of the text chose to illustrate moral versus immoral behavior through the lens of eating. Although the haphazard arrangement of the “intemperate” people implies over-consumption of food and drink, close examination of the image reveals otherwise. Even those who demonstrate their moral failings with their poor table manners and inappropriate feasting behavior don’t actually eat.

The Feast of Dives, Master of James IV of Scotland, Spinola Hours, Bruges and Ghent, 1510-20, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 18, fol. 21v

In this early 16th-century image, “Spinola Hours,” the cut-away view displays both the exterior and interior of a well-appointed dining room in a wealthy household. A retinue of servants brings various dishes to the well-fed gentleman’s table, including roast poultry rakishly decorated with one of its own feathers. More than just a slice of medieval life, this image depicts the biblical story of Lazarus and Dives (the Latin word for “Rich Man”). When Lazarus, a beggar, comes to the door asking for scraps from the table, the Rich Man sets his dogs on him. For medieval Christians, the Rich Man came to represent the epitome of gluttony, not only because he consumed food to excess, but because he failed to share his bounty with others less fortunate. One would expect such a figure to be shown lustily consuming the bounty of his table, but though he raises a bowl, suggesting the impending quaff, it remains a good distance from his mouth. Even a biblical figure closely associated with gluttony does not eat.

Images of feasting that appear in medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts illustrate the types of foods consumed by people at that time, elegant food presentation, and proper table manners. More importantly, they reveal medieval attitudes toward food. In the earlier Middle Ages, and in the context of books used by high-ranking clergy, such as the Regensburg Benedictional, it was desirable to implicate Judas as a sinner through his act of eating and to set up a contrast with the 11 more restrained apostles. Centuries later, as the concept of the seven deadly sins became more entrenched, concern seemed to increase about the depiction of eating, especially in manuscripts owned by wealthy laypeople who might easily be accused of gluttonous behavior at their feasts. The ambiguity revealed in the fact that people do not eat, especially in these later illustrations, expresses the medieval struggle to straddle the fine line between eating enough food to survive and eating to excess.

Send A Letter To the Editors