Psychedelic drugs, anthropology, art, commerce, 1960s counterculture, and indigenous culture collide in the stunningly vibrant and intricate yarn paintings of the Wixárika people of Western Mexico. On one level, these are psychedelic works fundamentally tied to peyote, the psychotropic drug that is integral to the Wixárika’s spiritual practices. On another, they are important documentation of a culture becoming commodified in the mid-20th century, in this case aided by a self-described shaman and a reporter-turned-anthropologist.

Psychedelic drugs, anthropology, art, commerce, 1960s counterculture, and indigenous culture collide in the stunningly vibrant and intricate yarn paintings of the Wixárika people of Western Mexico. On one level, these are psychedelic works fundamentally tied to peyote, the psychotropic drug that is integral to the Wixárika’s spiritual practices. On another, they are important documentation of a culture becoming commodified in the mid-20th century, in this case aided by a self-described shaman and a reporter-turned-anthropologist.

The yarn paintings comprising “The Spun Universe” exhibit, now on view at UCLA’s Fowler Museum, were primarily collected in the 1960s by Peter T. Furst, a UCLA-trained anthropologist who studied the Wixárika (commonly known as Huichol). According to Fowler curator Patrick A. Polk, Furst had been drawn to the Wixárika by his journalistic reporting and later academic interest regarding the uses of psychedelic drugs. As in many indigenous cultures in the Americas, Wixárika shamans ingested peyote, which they call hikuri, during religious ceremonies.

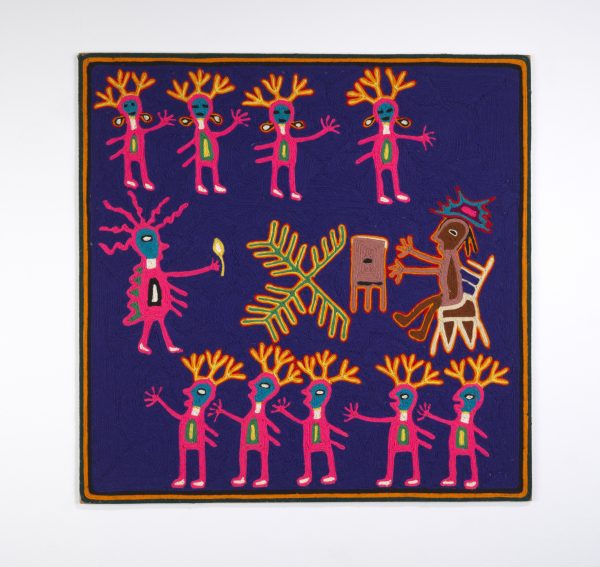

Untitled, Ramón Medina Silva, mid-1960s. Yarn, beeswax, composition board. Purchase courtesy of the Ford Foundation, X67.63; Fowler Museum at UCLA.

Norwegian ethnographer Carl Lumholtz first documented this in the 1890s, after staying among the Wixárika for about 10 months. “The plant, when taken, exhilarates the human system … it also produces colour visions,” wrote Lumholtz in his 1902 publication Unknown Mexico.

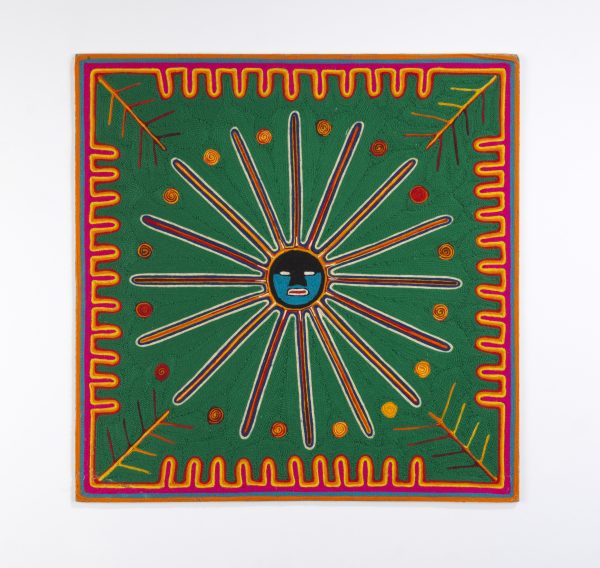

“Peyote is a fundamental element of the Wixárika belief system,” said Polk. “It’s a source of revelation, of spiritual connection, of healing … and has inherent sacredness beyond psychotropic properties.”

In 1965, Ramón Medina Silva, a Wixárika living in Guadalajara who claimed to be a shaman apprentice, became a primary guide to Furst and his colleague Barbara Meyerhoff. In describing his holistic belief system to the anthropologists—which included hallucinogenic visions based on deities such as Our Elder Brother Deer, Our Mother Blue Corn, and Our Grandfather Fire—Silva relied upon nierakate, drawings made with brightly colored yarn affixed to boards with beeswax.

Untitled, Ramón Medina Silva, mid-1960s. Yarn, beeswax, composition board. Purchase courtesy of the Ford Foundation, X67.51; Fowler Museum at UCLA.

The Wixárika, whose culture retained many pre-Columbian aspects due to their remote location in the Sierra Madre Occidental, were known for their artistic offerings and adornment of votive objects for religious ceremonies. Lumholtz described and illustrated many examples of small tablets and gourds decorated with spiritual motifs in Unknown Mexico. In the 1950s, they began to make simple, decorative versions of nierakate, an idea Furst traced back to Alfonso Soto Soria, a collector of Mexican folk art and museum director. According to Furst’s book Visions of a Huichol Shaman, Soria thought these “yarn paintings” would be intriguing for an exhibition he was putting on and as another type of folk art Wixárika artisans could produce for sale.

Mexican folk art was then becoming a hot commodity, championed by the Mexican government in its simultaneous midcentury pushes to improve living standards in remote indigenous communities and popularize and protect their artistic traditions. But as a medium to express his culture’s beliefs to outsiders like Furst, Silva’s artworks, and that of his wife Guadalupe de la Cruz Rios, were more intricate and narrative, distinctly apart from both the small, traditional religious offerings and the larger, more decorative nierakate pioneered in the ’50s with Soria’s encouragement.

Untitled, Ramón Medina Silva, mid-1960s. Yarn, beeswax, composition board. Purchase courtesy of the Ford Foundation, X67.72; Fowler Museum at UCLA.

While Silva’s status as a shaman has been questioned, Polk described him as a “culture broker,” using his own undeniable artistic talent to preserve the beliefs of his people and create a demand for the artwork he helped pioneer. Silva understood that he was “at the right place at the right time,” as Polk said, in terms of the heightened interest in both folk art and psychedelic art. With the encouragement of Furst, who bought many yarn paintings on behalf of UCLA and other institutions, Silva became world-renowned. In 1968, the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History staged a one-man exhibition of his work.

Silva’s style, sometimes down to the exact design, was quickly taken up by other Wixárika artisans and further popularized in the Mexican urban centers inhabited by Wixárika emigrants. “In the 1960s there was a confluence of research, popular interest, tourism, and traditional arts” around shamanic traditions, said Polk. Visitors to Guadalajara or Puerto Vallarta can still easily find psychedelic nierakate to take home as souvenirs, though they may not realize their purchase reflects more an indigenous people’s canny navigation of the art market than an ancient artistic practice.

Though some aspects of Silva’s, Furst’s, and Meyerhoff’s accounts of Wixárika culture were later disputed (all three are now deceased), the yarn paintings they brought to the wider world continued to be created by Wixárika artists like José Benitez Sánchez. “It lets [the Wixárika] give others their Technicolor visions of the universe,” said Polk.

Send A Letter To the Editors