A great novelty about Hawaii, at least among American states, is the extent of its ethnic diversity. White missionaries from the mainland and their descendants may have long dominated the island economy, but they don’t make up anything close to a majority of the population. Barely one in four residents is white, compared to more than three in four Americans nationally.

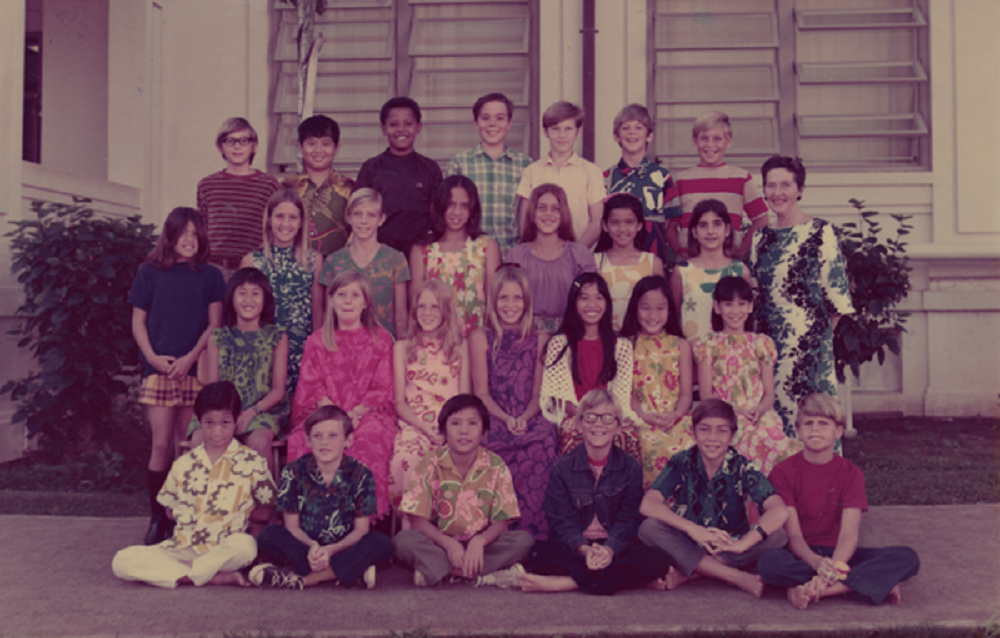

Various immigrant groups that supplied the lion’s share of labor in the heyday of the sugar and pineapple plantations came to live alongside one another. Most residents of Hawaii would be defined, elsewhere at least, partly as Asian American, but their place in the islands is so dominant that defining them as “Asian” is almost meaningless to local academics. Instead, they tend to refer to component groups, the descendants of Filipinos, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese immigrants, mostly from long ago. There are also Native Hawaiians and Micronesians, not to mention people from Portugal and elsewhere. And, in many cases, their children grew up together, forging distinctly mixed island identities as they intermarried. Today, 23 percent of people in Hawaii consider themselves to be ethnically mixed—true of only 3 percent of Americans. And unlike on the mainland, being hapa, or mixed, has become a core part of the identity of the islands.

Especially as we move deeper into the Pacific Century, America’s remote ocean outpost embodies many elements of our nation’s diversifying citizenry and of our planet’s increasingly interconnected future: As people struggle to get by, they need to find a way to get along with their global neighbors. This is especially true of Hawaii, but in miniature. And one way Hawaiians have done this is by creating a new, inclusive identity: “local.”

When I moved to Hawaii in 2013, I quickly realized how important high school is here. When two locals meet for the first time, they often ask: What school did you graduate from? They aren’t talking about universities; they are talking about high school, which acts as a sort of proxy for home ground in a state where discussions of race, ethnicity and local identity often take place in coded language to avoid offending. Political candidates actively tout their schools to send signals about their roots, circles of influence, and how many degrees of separation there are between them and the people they speak with. High school anchors the person in a unique place and time in other locals’ minds. Given the small-town nature of Hawaii, it also allows people to visualize a school, a neighborhood, and a way of life. It ultimately signals whether someone is authentically local or not.

This is true even of politicians who graduated from top-ranked schools on the Mainland. Former Honolulu Mayor Mufi Hannemann graduated from Harvard University, but in the islands, he can be seen as a graduate of the elite Iolani private school, a stone’s throw from Waikiki.

When I spoke to Hannemann in 2014 about why this is the case, he said that talking about high school signals something crucial in the islands—“that you’ll never forget your roots.” Speaking of Iolani, he added, “I’m still the same guy.”

In 2015, as part of a special project on race and ethnicity for the Honolulu-based media Civil Beat, I spoke with former Hawaii Gov. Ben Cayetano for a podcast on what it means to be “local” in the islands. Cayetano, who became America’s first Filipino-American state executive in the 1990s, suggested that poor immigrant communities in Honolulu didn’t, for the most part, have the space to carve out “balkanized” ethnic communities, as happened in places like Southern California with East Los Angeles, Koreatown, Little Tokyo, Little Phnom Penh, Little Armenia, and so many others.

In Cayetano’s childhood, Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, Portuguese, and even a Russian kid came of age on the same streets, attended each others’ birthday parties and religious celebrations, and even spoke the same pidgin English.

In such circumstances, he said, “You are forced to interact,” and learn about each other and yourselves. “And your racial identity sometimes gets a little murky.”

The resulting cultural mix, he said, is what a lot of people who grew up in the islands call “local.”

What constitutes “local” can provoke plenty of debate in the islands, including from Cayetano. And he acknowledged that the concept continues to evolve even now.

The former governor, now in his late 70s, says that being local is no longer just about being from a certain neighborhood, economic or social class. “It is the feeling, you feel local.”

“What’s interesting is that a lot of people come from the mainland and they … almost develop that same feeling because they buy into the local culture. And frankly some of the people who come from the mainland seem to care more about this state than the guys who are born here.”

In his telling, even new arrivals can aspire to something close to “local” status—at least these days. That’s significant given that 46 percent of people who live in the islands—which includes the large U.S. military presence—were born outside of the islands. It also helps to explain a common question directed toward non-locals: How long have you lived here?

Elsewhere, you could be forgiven for believing the questioner is simply making conversation. In Hawaii, such a query can be about something much more significant. Your answer can convey how committed you are—or aren’t—to the islands, whether you are just using Hawaii or have really taken to it, and whether you are connecting with the place. It even allows interlopers to know that they are outsiders, but feel at home in that. On some level, living in the islands for a long period of time can afford a non-local a surprising form of status; a little like the way a decade of sobriety can impress people at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting.

Time spent in Hawaii is, of course, an imperfect barometer of people’s acclimation. Some people live in the islands for decades and never really get the vibe. Others can rapidly develop an intuitive understanding of their adopted home and find their special place in it. My first-born son started to become local much faster than I expected. Born in Paris, he moved to Hawaii when he was 4 years old. English was his second language and it took him a couple months of living in the islands to speak it fluently, but by the time he was five he began to throw in the occasional term of pidgin and I’d sometimes overhear him playing with his superhero figurines, saying, in a singsong voice: “That’s a really good idea, brah.”

None of this is meant to suggest that Hawaii is, like its aloha-rich tourist propaganda, any sort of real paradise where everyone gets along. It is a complicated place with plenty of major problems, including when it comes to race, ethnicity and class. I’ve spoken with people who have recounted past harassment, bullying and worse in schoolyards, at roadside police stops and beyond, and it is sometimes linked to stereotypes about different ethnic groups.

Hawaii also has more homeless people per capita than any state, and the urban core of the capital offers a striking contrast in fate between the construction of glittering new residential towers and the ubiquitous homeless tent encampments. At its most extreme, the contrast creates a visual background reminiscent of the dystopian near-future Los Angeles in the film Blade Runner. Resentments around race, ethnicity, and wealth disparities in the most expensive state in the country sometimes result in surges of online anger and, less commonly, brawls in the real world.

Hawaii is changing too. In 2016, Honolulu continues to evolve into a new sort of global city—not a worldly megalopolis like New York or London, but a globally-influenced mid-sized city in the middle of the Pacific. Though “localism” still dominates outward identity politics, it’s worth examining where it may be used to skirt over issues of those excluded from the idyllic Hawaii.

With demographic trends suggesting that the U.S. will become a majority-minority nation in the 2040s, the country would do well to try to understand how local identities are fashioned, and how Hawaii is fashioning its own.

Send A Letter To the Editors