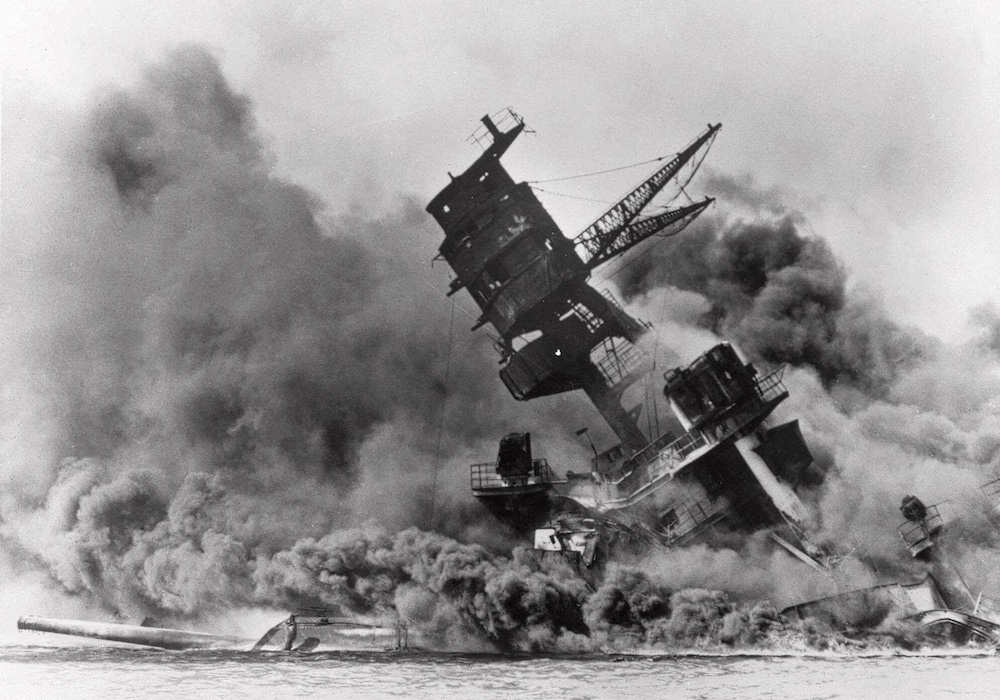

Smoke rises from the battleship USS Arizona as it sinks during the Dec. 7, 1941 Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The cyber age “gray zone” makes it hard to determine what the cyber equivalent of such an attack would be. Photo by Associated Press.

Last year, Russian intelligence mounted an unprecedented attack on the integrity of the U.S. election. Russian hackers broke into the email of the Democratic National Committee and of John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager, and released the stolen documents strategically via the website WikiLeaks to help Donald Trump. Or so the U.S. intelligence community found in a “high confidence” assessment that was partly declassified in early January.

While Donald Trump at first denied that the Russian intervention had occurred at all and still denies that it had any impact on the election, its significance can be judged from the fact that during the last month of the campaign he mentioned WikiLeaks at virtually every stop. In an election decided by just 70,000 votes in three states, it is hard to dismiss the possibility that the Russian intervention could, in fact, have tilted the outcome. That would make this the most consequential computer hack in history, but was it an act of war?

Certainly not in the classic sense. The Kremlin did not, after all, transgress America’s borders or the borders of an ally the United States is pledged to protect. It did not shoot down an American aircraft or sink an American ship. Those are the classic kinds of casus belli that have traditionally sparked hostilities. But such old-fashioned definitions of aggression do not seem fully adequate to deal with the cyber age, in which computers can be a far more potent weapon of war than a machine gun or a mortar.

Protesters stand around the statue of a Red Army soldier to prevent the Estonian government’s plan to move the Soviet-era monument honoring in Tallinn, April 22, 2007. The statue was subsequently removed, and Russian hackers are suspected of having temporarily disabled Estonia’s access to the internet with denial-of-service attacks in retaliation. Photo by NIPA, Timur Nisametdinov/Associated Press.

How should one treat incidents such as the one that occurred in 2007 when Russian hackers are suspected of having temporarily disabled Estonia’s access to the Internet with denial-of-service attacks in retaliation for the removal of a statue in Tallinn honoring World War II Soviet soldiers? Or the 2010 Stuxnet virus used by Israeli and U.S. intelligence to disable a thousand Iranian centrifuges? Or the 2012 attack, blamed on Iran, which disabled 30,000 computers belonging to the Saudi state oil company? Or the 2014 North Korean attack on Sony Pictures in retaliation for the release of a movie parodying North Korea? As the Harvard strategist Joseph Nye notes in the journal International Security, these events, and others like them, do not fall neatly into “the classic duality between war and peace,” occurring instead in a “gray zone” that defies an easy definition or response.

It is possible, to be sure, to imagine more severe cyberattacks that would more easily cross the threshold of open hostilities. “Talk of a ‘cyber Pearl Harbor’ first appeared in the 1990s,” Nye notes. “Since then, there have been warnings that hackers could contaminate the water supply, disrupt the financial system, and send airplanes on collision courses. In 2012 Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta cautioned that attackers could ‘shut down the power grid across large parts of the country.’” If such a massive attack were to occur—and if responsibility for it could be attributed with a high degree of certainty—one could imagine treating that as a casus belli requiring a response not just with computer viruses but with actual firepower.

But attacks such as Putin’s hacking of the 2016 election fall below that threshold, which is part of what makes them so attractive to relatively weak states such as Russia or North Korea: It allows them to maximize their ability to disrupt their enemies while minimizing the backlash. In fact, what consequence has Russia suffered for intervening in the U.S. election? Nothing beyond the expulsion of a few diplomats, which is hardly enough to make Putin rethink the efficacy of these tactics. Indeed, even the impact of those last-minute Obama sanctions was probably undermined by the conversations that Michael Flynn, Trump’s first national security adviser, secretly had with the Russian ambassador prior to the inauguration—talks in which he is suspected to have asked Putin to hold off on any retaliation in the expectation that once Trump became president he would ease tensions. Flynn subsequently had to resign after lying about those conversations. But even the growing Kremlin-gate scandal has not been enough to dissuade Putin from meddling in similar fashion in the Dutch, French, and German elections to support pro-Russian and anti-EU candidates.

While no one is suggesting that the U.S. should have started World War III over the Russian interference in our election, a more serious response was in order. It’s not hard to think of a range of appropriate responses: As I have suggested before, Obama could have asked the NSA to disclose embarrassing communications between Putin and his aides or details about all of the billions they are suspected of looting. Or he could have simply asked the NSA to fry Kremlin computer networks. A range of non-cyber responses could also have been entertained, such as providing arms to Ukraine to defend itself from Russian aggression or ratcheting up sanctions on Russia by kicking it out of the SWIFT system of inter-bank transfers. Of course now that Trump is president, there is scant hope of any response at all; the only issue is whether Trump will lift existing sanctions on Russia.

Obama hesitated to do more against Putin because every action carried the risk of unintended consequences and of sparking greater hostilities. But the greatest risk of all is relative inaction. By failing to respond more strongly to Russia’s election intervention, the U.S. risks legitimizing such “gray zone” attacks. Thus we can expect more of them in the future. They may not exactly be “acts of war,” but they can cause more damage than many kinetic attacks—and it can be much harder to know how to respond. Figuring out a doctrine of cyber war that includes everything from such low-level strikes to “cyber Pearl Harbors” will be one of the signal challenges for military and intelligence strategists in the 21st century.

Send A Letter To the Editors