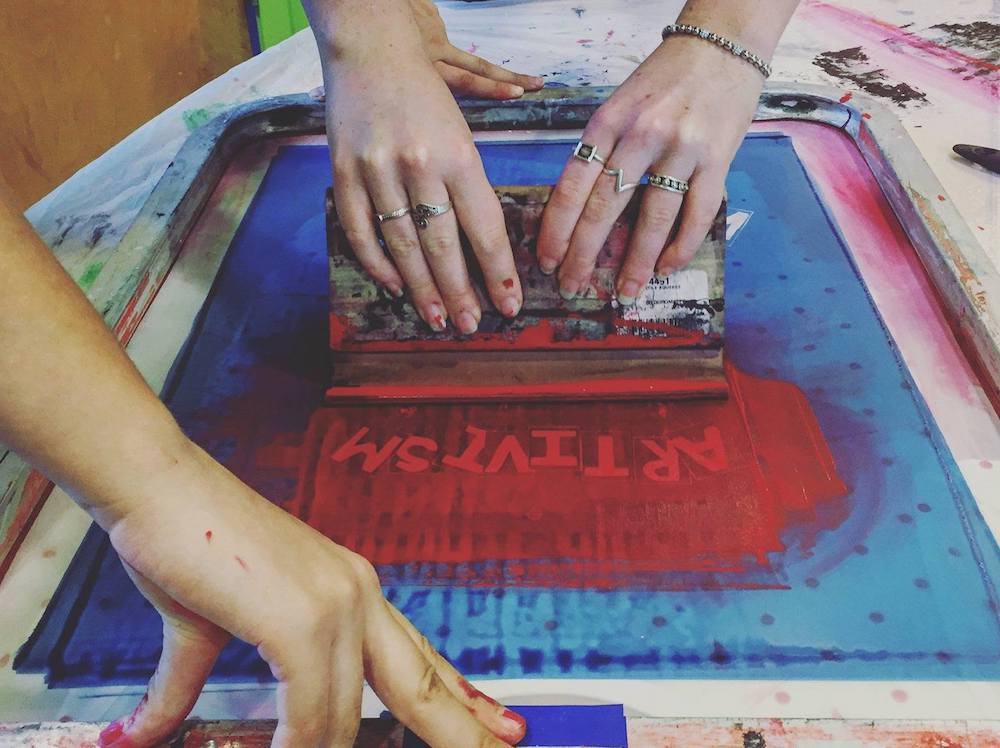

A program at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History. Photo courtesy of Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History.

Like many organizations, my museum, the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, struggles with two conflicting goals.

The museum should be for everyone in our community.

But it’s impossible to do a great job being for everyone. We’re more successful when we target particular communities or audiences and design experiences for them.

How do you reconcile the desire to be inclusive with the practical imperative to target? In the past, I’ve subscribed to the theory that an organization should target many different groups and types of people to serve a constellation of specific audiences.

But ultimately, that’s still targeting. And while it may be effective when it comes to marketing, it’s limiting if your mission is to bring different people together. It can lead to parallel programming: bike night for hipsters, bee night for hippies, family night for kiddies. And rarely the twain shall meet.

After much consideration and planning, we’re now approaching this challenge through social bridging. Researchers who study community development define social capital in two ways: Social bonding occurs among people with common backgrounds. Social bridging occurs among people from different walks of life.

A program at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History. Photo courtesy of Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History.

At our museum—like a lot of arts organizations—we saw how easily people used our institution as a place to bond. But we decided that it was more important for us to focus on bridging—explicitly bringing people together across differences in race, class, gender, age, culture, and background.

One of our core programming goals is to build social capital by forging unexpected connections between diverse collaborators and audience members. We intentionally develop events and exhibitions that match unlikely partners—opera singers and ukulele players, welders and knitters, Guggenheim winners and backyard artists. Our goal in doing this work is to build a more cohesive community.

We have been explicitly focusing on social bridging for five years now. What started as a series of experiments and happy accidents is now embedded in how we develop and evaluate projects. We’ve seen surprising and powerful results—visitors from different backgrounds getting to know each other, homeless people and museum volunteers working together, artists from different worlds building new collaborative projects. Visitors now spontaneously volunteer that “meeting new people” and “being part of a bigger community” are two of the things they love most about the museum experience.

This has led to a surprising outcome: We are turning programs for bonded groups into programs for social bridging. This isn’t just a philosophical shift—it’s also being driven by visitors’ behavior.

For example, when I first came to the museum, families with young children had one program designed for them: Family Art Day, a monthly Saturday workshop. For a couple of hours, an artist would lead a project. About 20 kids and adults would have a great time together in our little classroom. And then they would leave, staying away until the next Family Art Day.

Unsurprisingly, a whole lot of local people had no idea that Family Art Day existed. That meant that many families with young children didn’t know the museum was there for them at all. One mom asked me early in my tenure, “Do they even allow kids in that museum?”

So I made it a priority to welcome families not just for Family Art Day, but also for lots of museum experiences. We added a hands-on art activity into our ongoing First Friday festivals. We started layering all-ages participatory activities into our exhibitions. And we launched a new festival series, Third Friday, that offered dozens of hands-on activities and community workshops.

None of these new activities were aimed explicitly at families with children, but each welcomed them to take part alongside adults without children. As time went on, we noticed something that surprised us: Families stopped coming to Family Art Day. It got to the point where we would have hundreds of mixed-age families at the museum on a Friday night, and then only a handful the following day for Family Art Day.

After we opened new ways into our exhibitions and festivals, families with kids found more value in those intergenerational experiences than days made just for them. The intergenerational experiences offered something for everyone. Rather than a focused art activity in which families made their own project, people preferred varied festival environments. They preferred to take part in a range of activities, populated by diverse people and amenities (like a bar) not found at family-only events.

So we nixed Family Art Day.

The lesson held in other contexts. Single-speaker lectures languish while lightning talks—featuring, say, teen photographers, anthropologists, and professional dancers—are packed. Programs that bring diverse people together are more popular than those that serve distinct groups. Why fight it?

Teens participate in a program at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History. Photo courtesy of Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History.

And so, while we acknowledge that specific communities have particular assets and needs, we spend more time thinking about how to connect them than about how to serve each on its own. We don’t want any group to feel that the museum is strictly “theirs.” We’re comfortable being eclectic, chaotic even, if it means that a seven-year-old, a 17-year-old, and a 70-year-old all feel “at home” at the museum.

But focusing on social bridging also leads to tricky questions about working with new communities.

Just as many arts organizations serve narrow groups, many marginalized communities live in tight, bonded bubbles. When our museum started working with new communities, we emphasized the importance of participating in their space, on their terms. The result was work that was segregated geographically and culturally. It led to good bonding, but very little bridging.

We were able to start shifting from bonding to bridging when we sat down and talked honestly with community leaders about their assets and needs. For example, when we first started working with Senderos, an Oaxacan music and dance organization, we started on their terms, supporting their events as volunteer partners. But then, we realized—together—that each of our organizations had more to gain by bridging than bonding. We each were serving somewhat bonded audiences—theirs majority Latino, ours majority white. We each wanted to reach new people. And so we started being more strategic about ways to cross-promote, cross-program, and bridge our respective communities.

Our museum’s work with Senderos was somewhat influenced by a 2004 paper by Dr. Pia Moriarty on immigrant participatory arts in Silicon Valley. In the paper, Dr. Moriarty puts forward a paradigm of “bonded-bridging” to describe the way that ethnically-identified programs and organizations contribute to bridging in a majority-immigrant community. When an organization like Senderos shares Oaxacan practices with a multi-ethnic audience, they bond as a group sharing pride and culture, and they bridge with new audiences by inviting them into their cultural practice.

I’m still chewing on the balance between social bonding and bridging, especially with historically marginalized groups. But overall I’m hopeful that by focusing on social bridging, we can get away from targeted programs and move towards a more inclusive approach to building community.

Send A Letter To the Editors