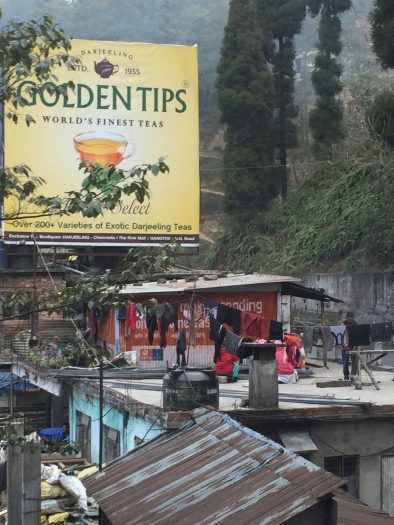

Darjeeling tea, which comes from a mountainous region of India’s West Bengal state, uses marketing to promote itself as an exotic export. Photo by Erika Rappaport.

Darjeeling tea is a world-renowned product that reliably flows from India’s highlands, where it has been grown for more than a century. But since early this summer, none of it has reached global markets.

A newly revived independence movement has cut tea exports, stopped the region’s tourism, and shut down schools. The Gorkhaland movement asks for independence from the state of West Bengal. Activists have long felt that this shift would secure rights and recognition for the Nepalese-speaking majority population.

While many distinct local issues and histories have driven this sub-nationalist movement, it has something in common with Brexit—and other current struggles over land, identity, and memory—in that they speak to unfinished business from an earlier age of empire and colonization. In Darjeeling, as in pro-Brexit parts of England, contemporary claims to independence rest on a memory of a benevolent empire that never existed.

Calls for an independent Gorkha state began in the first decade of the 20th century (and there have been other similar ethno-linguistic movements in the region and nearby areas). But the current conflict was sparked in May 2017, when Partha Chatterjee, the education minister for the Indian state of Bengal, announced that Bengali would be a compulsory subject for all grade levels in state schools.

This policy shift seemed a direct threat to the Nepali-speaking majority in Darjeeling. Bimal Gurung, president of Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM), the agency that rules the semi-autonomous Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA, created in 2012), responded with protests, and soon a handful of political parties demanded Gorkhaland separate from West Bengal. Strikes and clashes between police and GJM supporters escalated conflict and shut down the entire region’s economy. In late September the GJM ended the 104-day strike, but tensions have not yet subsided, as the political future of this area of West Bengal is not yet clear.

Darjeeling is the name of both a town and district situated in the lesser Himalaya at the northernmost part of the state of West Bengal. Protruding like a thumb between Nepal and Bhutan, Darjeeling sits below China and Sikkim, which ruled the lands before the British arrived. As both a real and imagined place, Darjeeling bares profound traces of its colonial past. These lands sustained the British imperial system starting in the 19th century.

Its altitude, climate, and spectacular natural beauty provided perfect conditions for tea growing and for refuge for British-colonial families escaping the heat of the plains. The many boarding schools in the area are reminders of a time when British families sent their children to school in the hill stations, fearing that the Indian climate would have an enervating effect on their offspring. While they built schools, shops, churches, and houses that approximated life in Britain, they also planted tea, and by 1874 there were 113 estates producing primarily for export markets, according to Sir Percival Griffiths’ The History of the Indian Tea Industry.

Contemporary Gorkha identity took root on these estates and in the military during the 19th century. When the British established plantations in India, they invented a new form of labor that technically was not chattel slavery but depended upon migrants from diverse parts of the empire. In Darjeeling, people originally from neighboring Nepal populated the labor force. Gorkha men and women developed a very distinctive identity derived from their sense of “displacement from Nepal and servitude in the colonial tea industry,” writes Sarah Besky in her recent study of these workers, The Darjeeling Distinction: Labor and Justice on Fair-Trade Tea Plantations in India.

Under the British, who categorized and defined their subject peoples in order to conquer them, Gorkha men came to be regarded as prized soldiers, especially loyal and courageous. They became the shock troops of the empire and were used to suppress colonial rebellions and fight small and large wars, famously battling Nazi German general Erwin Rommel’s forces in North Africa during the Second World War. When India gained independence in 1947, Gorkha soldiers were incorporated but remained separate regiments within the Indian army. Thus, Gorkha identity developed within a context of militarism and mobility, and carried a sense of service to the Indian state and the land.

The idea that Darjeeling is special has manifested itself in agitation for an independent Gorkhaland. Some of today’s protesters feel so culturally different and disparaged by their Bengali rulers that they even argue that they were more appreciated during the days of the Raj than in contemporary India. The resulting movement for Gorkhaland may eventually achieve statehood—but it’s unclear if that will solve the region’s problems, the roots of which lie in tea.

Darjeeling’s tea was not always so special. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was typically blended with other teas, including Chinese, and then sold under brand names such as Twining’s, Brooke Bond, and Lipton’s. But later in the 20th century, these same companies and the area’s planters began to publicize Darjeeling tea as superior to that produced in Assam and other areas of India and the Empire. The real differences in teas involve the origin of the plants, the constituents of the soil, and the altitude (among other factors), but the Darjeeling difference was rooted in the power of global advertising and international regulatory systems.

Ethnic tensions dating back to the colonial, tea-producing era of the British Raj are fueling a movement by the Nepali-speaking majority for independence. Photo by Erika Rappaport.

While marketers established Darjeeling’s reputation as the “Champagne of Teas,” this term gained comprehensive legal protections via the World Trade Organization, which granted it “Geographical Indication” (GI) status in 1999. GI status implies that products and places are unique. The WTO’s website notes, “A product’s quality, reputation or other characteristics can be determined by where it comes from. Geographical indications are place names (in some countries also words associated with a place) used to identify products that come from these places and have these characteristics (for example, “Champagne,” “Tequila” or “Roquefort”).”

GI Status thus accepts the notion of terroir, the idea that the totality of an environment is what makes some products special. Packaging, advertising, and trade literature reinforce such ideas. Cementing the linkages between tea and geography, the Indian Tea Board—a body under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry that overseas all of India’s production—currently promotes the tea with the tagline: “Darjeeling tea. As exotic and mysterious as the hills themselves.” The region, according to the board, is a place “where the breath of the Himalayas surrounds the traveller and the deep green valleys sing all around.”

Such publicity, and the Indian tea industry, has unwittingly perpetuated the racial, ethnic, gender, and class divisions that have long existed on the plantations. It need not have done so. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, local and national governments debated whether India should literally uproot the industry, universally seen as a European colonial institution. But the tea didn’t go anywhere.

British companies managed to hold on for some time before transferring power to the Bengali elite who resided in other parts of the state of West Bengal. Transforming this agrarian economy was too difficult, and the need for foreign exchange too great. So tea remained a crucial industry in independent India—so important that West Bengal is determined to hold onto Darjeeling and nearby tea-growing regions. To this day, tea laborers feel they grow the “finest” tea in the world, but they resent Bengal in part because they do not accrue the profits of their labor.

Tea is a delicious beverage and at times a profitable commodity. But whether or not Darjeeling remains part of West Bengal, its first need is a more diverse economy. Until it develops one, Darjeeling will remain too dependent on tea—and on the global forces that date to the British Raj.

Send A Letter To the Editors