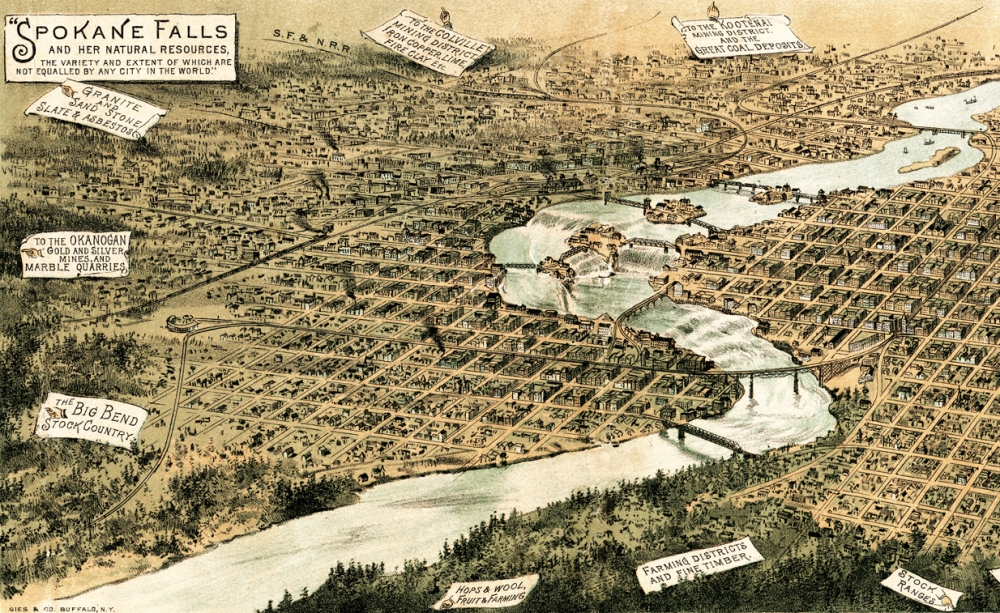

A map from the 1890s indicates how mining, water power, and other enterprises were turning Spokane into a boom town. Art courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In the spring of 1897, Spokane, Washington’s Spokesman-Review published an exposé of its city’s thriving red light district—known as Howard Street. The newspaper lingered on distasteful scenes in variety theaters with names like the Comique or the Coeur d’Alene: Places where a man could pick up a game of keno, watch a show, and—for the cost of a drink—enjoy the flirtations of “waiter girls” in short skirts. The most controversial and profitable feature of the Howard Street varieties were their curtained boxes, where the girls could be entertained on a closer basis.

In the spring of 1897, Spokane, Washington’s Spokesman-Review published an exposé of its city’s thriving red light district—known as Howard Street. The newspaper lingered on distasteful scenes in variety theaters with names like the Comique or the Coeur d’Alene: Places where a man could pick up a game of keno, watch a show, and—for the cost of a drink—enjoy the flirtations of “waiter girls” in short skirts. The most controversial and profitable feature of the Howard Street varieties were their curtained boxes, where the girls could be entertained on a closer basis.

No one, the Spokesman argued, objected to a reputable variety performance. The trouble came with the boxes, where “women employ their sensual charms” to entice “young men for whom this feverish life has a peculiar fascination.” Other Western cities had abolished this “hurrah” element, the newspaper continued, and prospered accordingly. Spokane enjoyed a beautiful natural setting; plainly put, “if the dives and the hurdy-gurdy resorts were suppressed,” the city would be altogether attractive.

On the surface, the newspaper’s critique was a matter of morals and prudishness, but in fact it was also part of what would become a decades-long debate about Spokane’s ability to control its own future. By the final years of the 19th century, Spokanites could proudly claim that their booming city was the urban hub—the center of transportation, commerce, and culture—of a large area of the Northwest they called the Inland Empire. Ministers, newspapermen, and reformers longed for Spokane to become a settled, cultured city, one they described lovingly in promotional brochures as graced by churches, middle-class homes, respectable theaters, and music clubs. But their vision faltered against the reality of entrenched business interests, who catered to the resource extraction industries that kept the town afloat.

Spokane’s dilemma was a problem that echoed throughout the American West, where towns yearned to come into their own, but remained economically dependent on the East. Spokane began its career as did many American hamlets: inconspicuous but ambitious nonetheless. The falls of the Spokane River were a gathering place for Native Americans, and a fur trading post existed in the region in the early 19th century. With the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1881, and the mineral discoveries in the Idaho panhandle that began in 1882, the town became a mining headquarters. Railroads made Spokane the supply and distribution point for the rich wheat farms of the Palouse. By 1888, rail lines stretched east, west, and south from Spokane, connecting Northwestern mines and farms with Eastern markets. The region’s population mushroomed from 350 in 1880 to 19,922 in 1890, a nearly 6,000 percent increase that was accompanied by a feverish building boom.

None of this development could have occurred without financing, markets, and transportation systems that Spokanites, in large part, did not control. The improvidence of the situation became clear with the Panic of 1893, when a burst railroad bubble and a precipitous drop in the gold supply plunged the U.S. into depression. Seven of Spokane’s ten banks closed in the panic, and, as the crisis progressed, 25 percent of Spokane’s buildings passed into the hands of a single European bank. But by the late 1890s, investors had recovered, and the city was again experiencing great growth.

Another important source of income for the town were the thousands of migratory, unattached young men, who worked in the mines, logging camps, and farms and came downtown, eager for diversion and companionship after months on the job. In the area between the Spokane River and the railroad tracks, these men found a carnival of saloons, brothels, lodging houses, gambling joints, dance halls, and variety theaters.

It was emblematic of the city’s resource-driven economy that the kingpins of Howard Street were Jacob “Dutch Jake” Goetz and Harry Baer. Goetz and Baer had staked early and lucrative claims in the fabulous Bunker Hill and Sullivan silver mine of northern Idaho, cashed out, and come to Spokane in the late 1880s. In time they built the deliciously ornate Coeur d’Alene resort, which catered to the fast crowd and to the laborers who poured into town. By May 1899, Goetz could brag to the Spokesman-Review that the Coeur d’Alene had a weekly payroll of $1,400, more than the electric and streetcar companies combined.

A vocal element in Spokane rejected the idea that the city had to accept an unbridled atmosphere in order to remain prosperous. In 1897 and 1899 they launched morality drives, aimed at the Howard Street establishments. These efforts followed similar paths: ministerial outrage, political promises, public debate, temporary victory, and ultimately, quiet failure.

Reformers wondered whether Spokane’s vice district marked it as a place outside the pale of decent American life. If Spokane could not lay claim to solid, Victorian decency, why would good families move there? How could the city enjoy above-the-board growth if it felt like the setting of a cheap western novel? As one Protestant minister put it in January 1897, his neighbors had to recognize that theirs was a hometown, “not a mining camp on the border of civilization.”

But even as Spokane’s reformers railed, its fortunes roared along and Howard Street became even more depraved. Slot machines proliferated in the red light district, the seedier saloons had introduced cubby holes—the purpose of which was obvious—accessible from side doors, and the boozy carousing in the private theater boxes had surely not abated. Worse yet, violations of the law occurred with the winking consent of some authorities. By 1899, only two years after its earlier exposé, the Spokesman-Review was still targeting the Coeur d’Alene resort—with its theater, bathhouses, and gambling halls right next door to City Hall—arguing that it would be shut down anywhere else in the U.S. Men fresh from the Klondike, the newspaper opined, had seen nothing so wicked in the wilds of Dawson City.

Things escalated that fall, just days before the opening of the Industrial Exposition, a fair promoting the products of the Inland Northwest. Great numbers of visitors were expected, many of whom considered variety theaters amongst Spokane’s most attractive diversions. At the last minute city fathers engaged in a battle royale over the renewal of business licenses for the Stockholm, Comique, and Coeur d’Alene resorts.

On paper, Spokane’s 1899 city council looked like a group that could agree with itself: white, Republican, middle-aged businessmen who had lived in Spokane for some time. Yet they split evenly on the question of variety theater licensing. At one point, after the reform crowd had momentarily gained the upper hand, councilman James Omo rejoined with a gambit, a set of “shut tight” resolutions that would align Spokane to a strict moral standard: Variety theaters closed, gambling laws enforced, Sunday closures instituted. The choice between profits and morality was at the heart of Omo’s bluff, though he claimed that the $30,000 the city gathered annually from vice district licenses and fines on gamblers and prostitutes was immaterial to him. Remarkably, Omo’s resolutions passed.

But that lasted only for one day. A large group of wholesalers, retailers, property owners, and community giants immediately submitted a petition requesting licenses for decent variety shows. With all of their investments in Spokane, these merchants did not want to hamper the “growth of natural prosperity in the community.” The petition contained an important caveat: the variety theaters must abide the law; more to the point, the private boxes, with their obvious sexual purpose, must close. Perhaps the theaters did present mindless, romping shows, but if their worst features—namely, sex and gambling—were eliminated what, precisely, was the problem?

Local clergymen tried to shame the bourgeoisie into accepting reform (was money their god? an Episcopal bishop asked), but with proposed revenues in the offing, the city council rescinded the “holiness” resolutions and licensed the three theaters just in time for the Exposition. With this conclusion to the 1899 affair, Spokanites showed themselves to be more concerned with the immediate realities of the bottom line than with staid, Victorian ideals, or some future Spokane that only existed in their dreams.

The town continued to boom along with extractive industries—especially lumber—in the first years of the 20th century, when its population rose from 36,848 in 1900 to 104,402 in 1910. This growth meant real power for the Howard Street kingpins, heightening the variety theater dilemma. The municipal elections in 1901, 1903, and 1905 yielded administrations friendly to the vice district.

It was only in 1908, after years of morality campaigns, that a coalition of ministers, temperance advocates, civic boosters, and progressives mustered the political will needed to enforce the anti-vice laws. They did so, in large part, by convincing their fellow Spokanites that more sustainable growth would come through building a “home city” than a place that capitalized on the fluid lives of migrant laborers.

On January 10, 1908, the chief of police notified downtown resorts that either the liquor or the women had to go. Honest application of the law spelled the end of Spokane’s variety theaters, which gave their final performances on January 11, 1908. After all, as Dutch Jake remarked, there was no money in it without the women. With that, middle-class Spokane cast its lot with bungalows and schoolhouses rather than flophouses and honky-tonks. The market for sin did not, of course, entirely disappear, and neither did the city’s dependence on outside investment. What changed was the willingness of the bourgeoisie to accept a reputation for frontier revelry in the name of profits.

Send A Letter To the Editors