Producer Rick Hall, the “father of the Muscle Shoals sound,” attends the 56th Annual Grammy Awards in Los Angeles in January, 2014. Photo courtesy of Todd Williamson/Associated Press.

It was 1975, and the British rocker had traveled to Sheffield, Alabama, with a specific mission in mind: He wanted to record at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio with the musicians who created Aretha Franklin’s unforgettable, hit-making sound. Before she made the pilgrimage down South, Franklin was a Detroit gospel singer beginning to find success as a pop singer. She recorded her album “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Loved You)” in Alabama.

Stewart was seeking the rhythm section that Mavis Staples had called out to on “I’ll Take You There.” But instead of the shaped-by-their-struggles black musicians he expected to find, when he showed up Stewart met a bunch of white Alabama fellas—the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section.

“We looked like—you know, short hair, you know just ‘Duh?’ you know, guys that worked at the supermarket or something,” bassist David Hood later told NPR’s Weekend Edition.

Stewart asked for a word with his producer, Tom Dowd of Atlantic Records. Surely Dowd had lied to him.

But no. Appearances aside, the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section were crack instrumentalists who, beginning in the mid-1960s, were coveted as collaborators by some of the biggest names in the recording industry.

Their singular talent was being able to shape-shift to fit virtually any artist. The Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section aimed to sound like Aretha when backing her up. When the Rolling Stones were in the studio in 1969, the Swampers, as they were known, had guided the British blues-rockers to three timeless songs in as many days of recording: “Brown Sugar,” “Wild Horses,” and “You Gotta Move.”

And when Stewart arrived in 1975, all four Swampers—David Hood, drummer Roger Hawkins, pianist Barry Beckett and guitar player Jimmy Johnson—were ready to sound like Rod.

The four men had become known for their impeccable rhythm and ability to play with anyone when they were the house band at another venue. FAME Studios—an acronym for Florence Alabama Music Enterprises—allowed the young musicians to find work doing what they loved. FAME attracted great talent.

The legendary recording studio at 3614 Jackson Highway in Muscle Shoals. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Muscle Shoals, in northwest Alabama near the Tennessee state line, sits about halfway between the blues and jazz bars of Memphis and the honky-tonks of Nashville. The Muscle Shoals area includes Sheffield, Tuscumbia, Florence and, of course, Muscle Shoals. With a regional population of about 147,000 according to ESRI data, the area is steeped in a rich regional brew of R&B, country, rock, gospel, and soul, and the Swampers had an instinctive feel for each genre and how to weave them into sounds that were both rootsy and authentic, yet also startlingly original.

The region’s first hit had come from FAME, Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On.” Wilson Pickett and Otis Redding recorded there. “When A Man Loves A Woman,” Percy Sledge’s unforgettable hit, started its life at FAME. This talent built a reputation that drew more musical artists to Alabama’s quiet northwestern corner. But the members of the lauded rhythm section also wanted a stake in ownership, and FAME owner Rick Hall wasn’t interested in offering that. (Hall, known as the father of the Muscle Shoals sound, died this week at 85, after a battle with cancer.)

Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler had worked with the Swampers, and he saw an opportunity. The musicians found an available space, a concrete block structure on Jackson Highway. The building was constructed before World War II, part of a planned subdivision that never came to be. Henry Ford had planned to build an auto manufacturing center in the area, according to the studio’s National Register of Historic Places application. When he withdrew those plans, the area fell into a recession.

The structure and several nearby became part of a blind factory. Years later, the 25 by 68 square-foot building would become a recording studio, with Wexler’s financial support. Hood, Hawkins, Beckett, and Johnson would become studio owners and, over the years, grow the area’s musical reputation.

So many of the songs recorded at 3614 Jackson Highway and its successor, the studio’s second location at 1000 Alabama Avenue, remain classics. The studio’s unusual sonic qualities are evident even on The Black Keys’ Brothers, recorded in the original studio but without the benefit of its original musicians. That 2009 album was the duo’s first Grammy Award winner, and it has staying power.

The Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section’s legendary recordings are emblematic of America: a melding of sounds and personalities, an opportunity for dissimilar people to bring out the best in one another. That’s rarely easy in the best of times, and the Swampers certainly weren’t living in them. The studio got its start in the turbulent late 1960s. The front line of the Civil Rights battle was only about 100 miles away in Birmingham. But artists of all skin tones found room for expression in the studio and others in the Muscle Shoals area.

“I could see that Southern whites liked their music uncompromisingly black,” Wexler wrote in his autobiography, Rhythm and the Blues: A Life in American Music. “Despite the ugly legacy of Jim Crow, their white hearts and minds were gripped, it would seem, forevermore.”

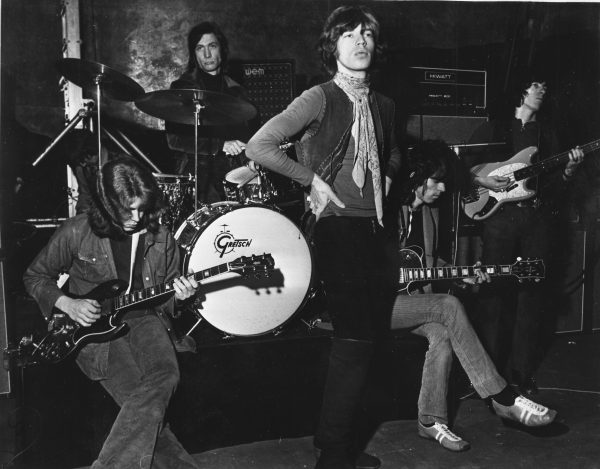

The Rolling Stones, rehearsing before a 1969 concert on the stage of the Saville Theatre in London. Photo courtesy of Peter Kemp/Associated Press.

The Swampers were locals who made history without leaving northwest Alabama. They built a legacy of working with other musicians—from Paul Simon and Etta James, to Clarence Carter and Bob Seger—without regard to race any more than to musical genre.

A half-century after they first came together, their influence and legacy have spanned generations. Patterson Hood grew up around the bands that sought his Swamper father David’s expertise, and it shaped his own artistic future. Hood went on to found the alt-country Southern rock band Drive-By Truckers with fellow Shoals native Mike Cooley.

Former Drive-By Truckers bandmate Jason Isbell has made his own mark on the Americana charts, thanks to his hardscrabble but smooth vocals and introspective songwriting.

John Paul White, formerly of the band The Civil Wars, is now a co-owner of Florence-based Single Lock Records. Birmingham-based St. Paul and the Broken Bones released its debut effort on the label, whose lineup includes White himself, Nicole Atkins, and other modern hitmakers. It’s difficult to keep up with the rosters of some bands, as members often collaborate or belong to multiple projects. But it’s clear that locals and the international talent drawn to the still-quiet area are just as quick to work together as they were in the Swampers’ day.

There are more studios in the Shoals now than anyone can reliably count. FAME continues to record greats, including Isbell, Nashville Star winner Angela Hacker, and Gary Nichols of the Grammy-winning bluegrass band The SteelDrivers. Muscle Shoals Sound was recently restored to its former glory, thanks to investment by Beats Electronics, the headphone and speaker company founded by rapper Dr. Dre and music producer Jimmy Iovine.

And although the earlier split between the musicians and Hall meant that there was tension between FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound for some time, these days the area’s two best-known studios collaborate to promote the area’s musical enticements.

Although the studios were a creative oasis for visiting musicians, they never were entirely shut off from the problems around them. Aretha Franklin, although she clicked with the musicians, decided not to return to Alabama after a racially charged incident outside of the studio.

But inside the studios, nothing was more important than working together to create great music. Decades later, Johnson offered a guess as to why the Ku Klux Klan tolerated the racially mixed enterprises: They liked the sound, too.

Like so many others before and after him, Stewart, the British soul man, found in Muscle Shoals not only the musicians he sought, but also something decidedly American: a collaborative environment where many influences join to show that the sum can be greater than the parts.

Send A Letter To the Editors