View of Glacier National Park’s Going-to-the-Sun Road, near Logan Pass. Photo courtesy of Glacier NPS/Flickr.

In 1872, Congress created the first national park, Yellowstone, so that its scenic features would be “dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” Other parks followed, including Sequoia and Yosemite in 1890, Mount Rainier in 1899, and Crater Lake in 1902. In 1916, Congress passed the Organic Act creating the National Park Service and directing it “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

In 1872, Congress created the first national park, Yellowstone, so that its scenic features would be “dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” Other parks followed, including Sequoia and Yosemite in 1890, Mount Rainier in 1899, and Crater Lake in 1902. In 1916, Congress passed the Organic Act creating the National Park Service and directing it “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Ever since, the Park Service has guarded some of the planet’s most spectacular scenery, leaving it, at least seemingly, unimpaired. To be sure, park officials invited guests in as they promoted “the enjoyment of future generations,” but human enterprise was meant to be confined to the hotels, visitor centers, and roads that dominated small portions of parks—the very places where, today, crowded park gift shops overflow with stuffed animals, and gas-guzzling RVs, SUVs, and minivans circle crowded parking lots. Beyond the traffic and tourist zones, parks have become critical nurseries for threatened biodiversity, as well as repositories for a uniquely American sense of national identity that is invariably expressed by photos of vast, empty vistas with grizzlies scattered in the foreground, hawks hovering skyward, and mountain crags holding the rest of the world at bay.

In this telling of the tale, America’s national parks remain wild and untouched. But that story is too simple. Parks always have been imperfect vehicles for noble protectionism—and few places demonstrate this as well as the Rocky Mountain region of northwestern Montana known today as Glacier National Park. This special place has glaciers, of course, and also rugged peaks, hundreds of lakes, and almost 3,000 miles of streams; it spans more than a million acres and straddles the Continental Divide. For many Americans, Glacier has long represented a wilderness frontier where unadulterated nature reigns.

But, in fact, human history and culture permeate Glacier, a place shaped by Native Americans’ dependence on the land, conservationists’ efforts to enshrine its beauty, and corporate America’s exploitation of its treasures. The Blackfeet have for centuries called it the “Backbone of the World,” the source of spiritual power and life forces that animate indigenous life and tradition. The American conservationist George Bird Grinnell dubbed it the “Crown of the Continent” and considered it an ideal place to preserve for national identity and culture. Louis Hill, the president of the Great Northern Railway, sold it as “everybody’s Park,” a symbolic place where Americans might encounter the source of the nation’s greatness. In broad outlines, Glacier’s unnatural natural history is shared by many of the nation’s beloved wilderness parks.

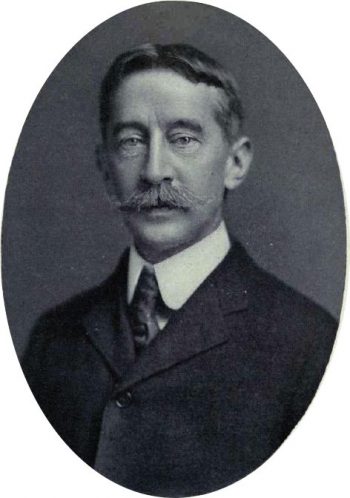

In large part, Glacier owed its establishment to Grinnell, a scientist, writer, and conservationist from New York who first visited northwestern Montana in 1885. Grinnell knew magnificent scenery—he had explored Yellowstone National Park with the U.S. Army in 1875—but Montana’s Rockies awed him. Launching from the state’s St. Mary country, he climbed into the mountains, hunted bighorn sheep and fished trout, met a party of Kootenais traveling from their homeland west of the divide, saw glaciers (including what is now known as Grinnell Glacier), and basked in the colorful “artist’s palette” of the wilderness.

In his writings, Grinnell ignored plain evidence of the human impacts that had been wrought there by native peoples, choosing instead to wax poetic about nature, and nature alone. As the historian Mark David Spence revealed in his book Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks, Grinnell relied on Blackfeet guides to accompany him over ridges and along Indian trails, but in his journal, he wrote of these places as “absolutely virgin ground … with no sign of previous passage.” A short time later, Grinnell wrote about the native hunting camps in the area. That Grinnell could both describe and share in indigenous presence and not acknowledge its role in shaping the land represented cognitive dissonance of a high order. His rhetorical erasure of obvious human impact became a model for how Americans thought of national parks: unpeopled, untouched—in short, pure nature.

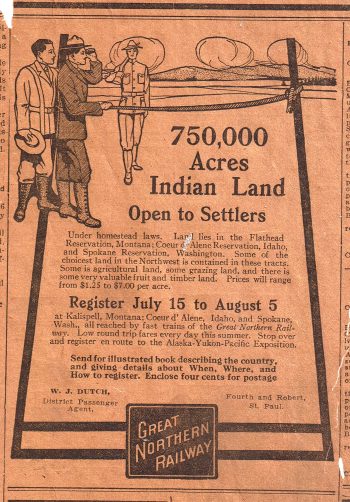

Newspaper ad from a St. Paul, Minnesota newspaper, 1909. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Grinnell wanted to create a nature reserve to protect the eastern flank of the Rockies. Doing so, however, would require wresting the land from the Blackfeet. During a trip in 1891, he hit upon a way to smooth the process: get the U.S. government to obtain the land in a would-be bid for its natural resources. At the time, many prospectors were clambering through the mountains, hoping to find rich mineral deposits. Grinnell, who did not believe such riches would materialize, saw these men as a threat to his park vision. U.S. government officials, too, were suspicious of the miners, whose disorderly behavior posed a threat to tenuous peace on the Blackfeet Reservation.

On behalf of the federal government, which wanted to stay involved to keep prospectors in check, Grinnell helped negotiate the cession of Blackfeet lands to open some 800,000 acres to prospecting. In short, but tense, negotiations in September 1895, the Blackfeet got the government to raise its payment for the cession to $1.5 million and ensured that tribal members could continue cutting timber, hunting, and fishing in the ceded area while it remained public land. Selling the land without maintaining access to such resources would have been unthinkable for tribal leaders, according to historian Louis Warren in The Hunter’s Game: Poachers and Conservationists in Twentieth-Century America. Bison were nearly extinct, and the Blackfeet had been losing territory to the United States for decades. They relied on what this coveted bit of land provided them, spiritually and materially.

Within two years of completing the negotiations, the land became part of the Lewis and Clark Forest Reserve; by 1902, as Grinnell had predicted, the hoped-for mineral boom busted, and the miners had cleared out. With new boundaries etched on the map, the mountains’ glaciers and streams now were wrapped in a federal mantle, not a tribal one, and soon nature lovers began debating and restricting the Blackfeet’s rights to continue cutting timber and taking animals from the reserve. Disagreements continued for decades, intensifying once Congress fulfilled Grinnell’s long-held dream and made Glacier a national park in 1910. Again, the United States ignored the centrality of human activity on the lands.

The cognitive dissonance would only amplify as time went on—thanks, this time around, to the efforts of the Great Northern Railway to popularize the park. When completed in 1893, the Great Northern line connected St. Paul, Minnesota, to Seattle, Washington. Louis Hill, the railroad’s president, knew and adored the northern Rockies, much like Grinnell. He believed they could serve as a salve for multiplying social problems in America. Like many white men of wealth, Hill, who lived in St. Paul, thought early 20th-century society had become over-civilized, with too many meaningless tasks filling time, and he searched for a more authentic life. Wilderness symbolized authenticity, because nature, by its essential definition, was the antithesis of the artificial. He joined Grinnell in lobbying Congress to create Glacier National Park.

Portrait of George Bird Grinnell. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hill’s motives weren’t entirely lofty. Glacier National Park’s backcountry trails, glacier-fed streams, and dominating peaks made it ideal for well-heeled tourists who wanted to be rejuvenated by wild mountain air and water—and the Great Northern, which traveled through miles and miles of undeveloped land, was ready and able to provide a way for nature seekers to get there. Glacier National Park made for a perfect marketing opportunity. According to historian Marguerite Shaffer, Hill adopted what had been a regional tourist slogan and nationalized it, plastering “See America First” on promotional material all across the nation.

Hill made certain that well-heeled tourists were comfortable amid a raw wilderness landscape. Visitors might hike or fish, but they rarely ventured far from the Great Northern’s orbit of influence. The newly built Glacier Park Hotel and Many Glacier Hotel offered first-class accommodations with rustic touches, including giant logs commanding the so-called Forest Lobby. Hotels blended local materials with cosmopolitan touches, including a Japanese couple serving tea—a not-so-subtle nod to the railway’s Oriental Limited line and its steamship company with commercial interests throughout the Pacific Rim. Chalets modeled on Alpine designs provided relative comfort (slightly) further away from the rail lines and lakefront lodgings. Blackfeet imagery and artifacts were ubiquitous. A teepee village on the hotel lawn offered families four beds and an authentic Western outdoors experience for $0.50 a night.

Hill regularly invited writers and artists into Glacier, generating good copy for the park and for his corporation, a practice that continued even after he retired. Many visitors, predictably, framed the park as an idyll. Writer and educator Margaret Thompson ended her 1936 book High Trails of Glacier National Park with a typical sentiment. “No other temple of worship has the power to bring one more truly into harmony with the sublime,” she wrote. We can recognize this rhetoric of nature today in the suggestion that Glacier—and perhaps all national parks—assert consensus amid seas of consternation, and that true wilderness rises above the fray of human activity and ambition.

Today, Glacier National Park faces many threats, not least among them climate change, which is shrinking the region’s namesake ice sheets. Ten of the park’s 39 named glaciers have shrunk by more than half in the last 50 years. Some scientists predict that Glacier National Park will be glacier-free by the time a child conceived today is eligible to drive a car. Tourists, hoping to see the glaciers before they’re gone, flock to the park, consuming fossil fuels that accelerate the warming that melts the glaciers away. As always, when tourists go to consume nature, they see a side of culture with their main dish.

Send A Letter To the Editors