Portraits of Loyalty

Shane Sato Depicts Japanese-American Veterans Who Fought for the Country That Imprisoned Their Friends and Families

Growing up as a Japanese American in a Los Angeles suburb, Shane Sato says, he felt “safe and comfortable” and had little, if any, experience with racism or prejudice. Only later in life did he learn about the internment of Japanese Americans in U.S. concentration camps during World War II, and about the thousands of Japanese Americans who fought for the United States during that war—even as some of their families were being held in camps and treated as non-citizens.

Sato’s photo series, “The Go For Broke Spirit: Portraits of Courage,” which was exhibited earlier this year at the Go For Broke National Education Center in Los Angeles, records the images and shares the stories of many of these veterans. This is an edited and condensed version of a conversation between Sato and Zócalo.

I was born here in Los Angeles, but my dad’s side was from Hawai‘i. The Japanese Americans in Hawai‘i weren’t interned in concentration camps during World War II, because they were more than 50 percent of the workforce, and without them, the islands would’ve shut down economically. A few of my uncles, on my dad’s side, fought in the 100th Infantry Battalion of the U.S. Army. Some of them might have been in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, but they passed away such a long time ago that we didn’t get a lot of information. My portrait series is of veterans who were in the 100th, the 442nd, and the Military Intelligence Service.

On my mom’s side they were from Visalia, California, so they were put in a concentration camp in Poston, Arizona. So my family had both experiences: One side didn’t go to camps but they fought in the war; the other side was interned and lost their land.

I tried to get personal stories from the veterans. In Hawai‘i we call it ‘talk story,’ and it’s something where people are just hanging out, talking, and they start telling their stories, personal stories.

It wasn’t easy. I’m Sansei, or third-generation Japanese American. But for the Nisei—or second-generation—like my mom and my dad, it was almost universal that they didn’t talk to their kids about the war or talk about the camps. Some say it was too traumatic or it was too shameful. So all my friends didn’t know about this until we were much older.

To get the men even to take the photos was a challenge in itself. The best way I found to obtain their cooperation—what I called my secret weapon—was to find the one lady who all the veterans talk to. There’s always someone who’s just hanging out, drinking with the veterans. And they would congregate around her. And the veterans would do anything that she asked.

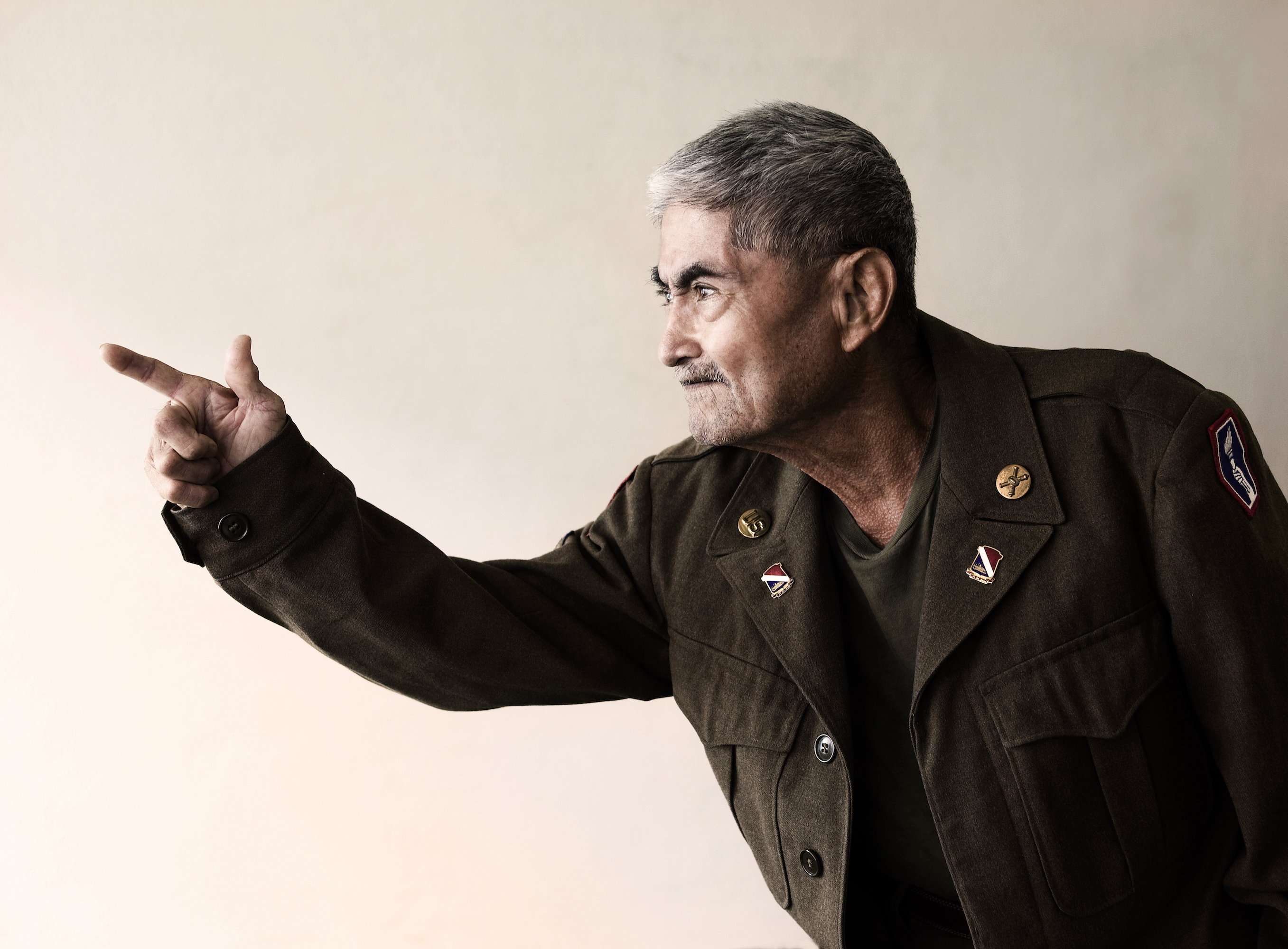

The hardest part was to get them to put the uniform on. Some still would not do it, and I can understand that. I’m lucky enough that when I was working in Hollywood, I worked with a lot of celebrities. I worked on movie sets, things like that. And they don’t give you a lot of time, nor did they give you a lot of input. So it’s kind of the same thing with the veterans. I study their faces and decide what I want to try and bring out, what I know of them. Are they proud that they made it? Are they reflecting? Are they sad for what happened? I remember one man was crying the whole time, and I got him to just kind of glance up. And that’s another thing with Nisei men: Very rarely do you get a lot of emotion out of them. They’re very stoic, especially with photos.

I spent a lot of time working on the feel of these pictures, and I did a lot of tests. Asian Americans were always portrayed as weak, or feeble, or goofy—never strong. What I decided to do was add a lot of contrast. For me, that adds strength. And for this series, I desaturated the photos and I did many layers of work. I didn’t want to make it too glamorous or too bright. It should be a somber mood, but strong. Even if the veteran is glad he survived, it’s still something that he had to go through.

There was one veteran I was talking to, and we did a little interview over the phone. And he said at the end, “Can I tell you something?” I said sure. And he went on to tell me that he was a medic, and how this soldier had died in his arms. And he knew the man, and he felt that if he’d done his job better he could’ve saved his life. And he said he’d never told that story. He told me he wanted to get that off his chest. And so he had never told that story for 70 years. He kept that inside him.

I hope this series will bring back that history, and let not only younger Japanese Americans—but all Americans—know that this existed, that the camps existed, that it should never happen again.

Send A Letter To the Editors