Illustration by Celia Jacobs.

No house on earth means more to me than my paternal grandparents’ small blue home near the bottom of a windswept hill in the Bay Area city of San Mateo.

I’ve entered this place thousands of times; I even lived there for a few months when I was 7. But this visit will be different.

While 420 Voelker Drive still belongs to my family, my grandparents have died and my uncle has moved in. He has a roommate, a generous woman who will greet me warmly and make dinner, but isn’t a relative. Before she and her son moved in with my uncle, they didn’t have a home.

This is a love story about California housing.

In this state, homes and dreams have always been emotionally intertwined. Now the dream of owning a house is out of reach for many: Housing of all kinds has become too scarce and too expensive. As a member of the fourth generation of my California clan to make a home here, I worry about what this may mean for our future and for all our families.

In 2011, I took on a big mortgage to buy a small, sunbeaten 1905 house in the San Gabriel Valley. Keeping up the place has been a struggle, but it caused me to see something new about California housing: Our houses and apartments are very old. The median age of a California dwelling is 46 years, while the national median age is 37. Our houses have faded and flipped, had their value destroyed by recession and disasters, and been run down and remodeled. And so, many of our homes have come to feel less like benefits and more like burdens.

Sometimes, our houses break our hearts.

To get an intimate understanding of Californians’ changing relationship with our homes, I realized that I needed to see the houses themselves. So this fall, I returned to six different homes that have been owned by my extended family during the last century.

The two sides of my family represent different strands of the California Dream. My dad’s side migrated here early in the 20th century to seek fortune and serve the military. Over a century, that middle-class family has produced teachers, journalists, and various other educated professionals. My mom’s even bigger clan of Dust Bowl Okies toiled in the orange packing houses and aerospace factories of Southern California, and now they are mostly truck drivers, caregivers, and office workers.

On this personal journey, I would often find myself asking: Do we still own our houses and the dreams they embody?

Or do they now own us?

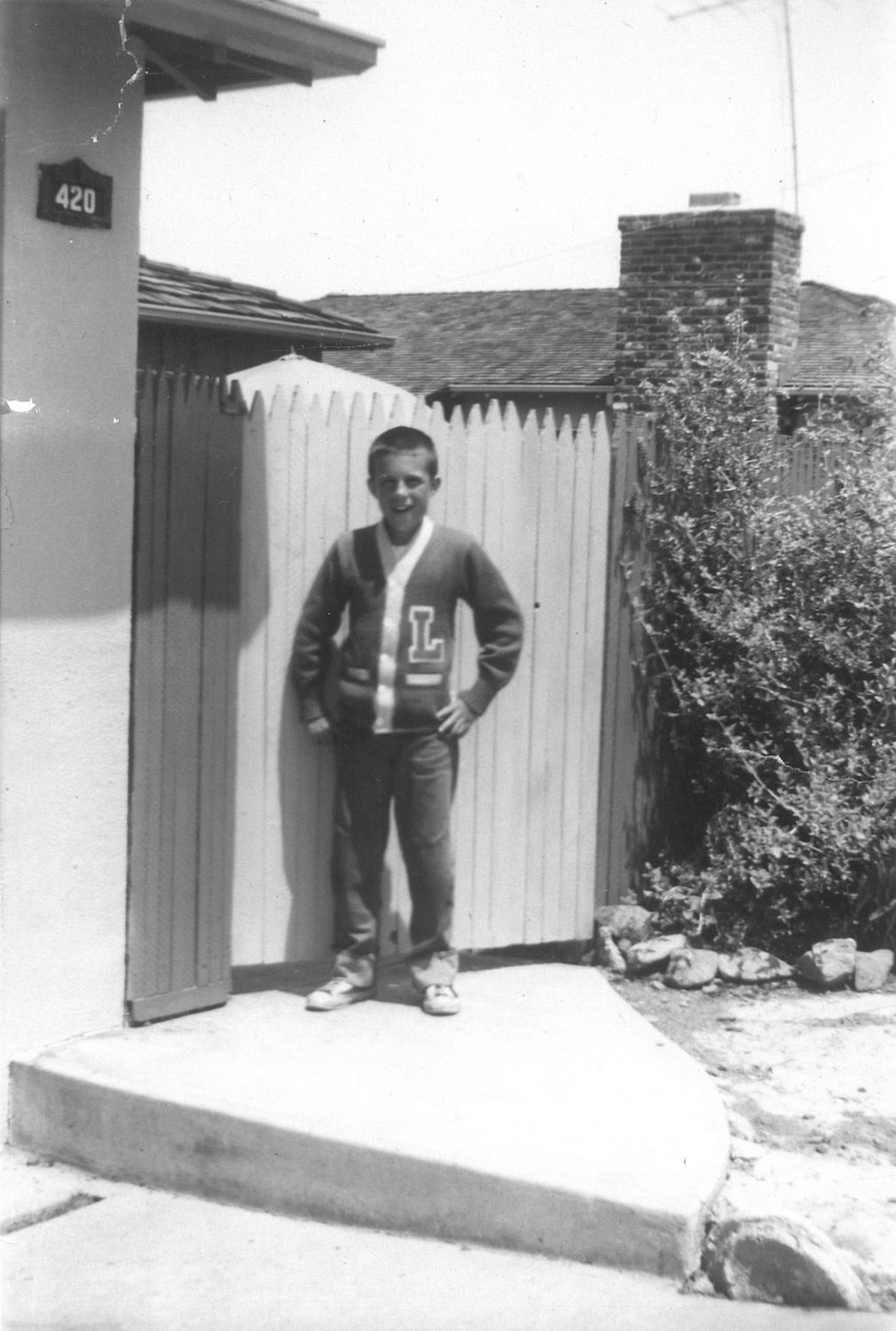

420 VOELKER DRIVE, SAN MATEO

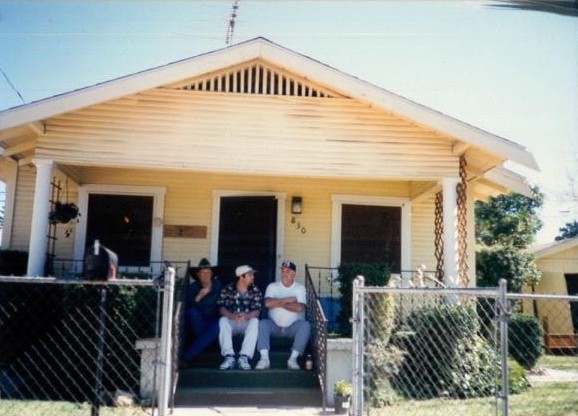

Dante Walton, Jim Mathews, and Gina Cooper stand in front of the home they share in San Mateo. Photo by Santiago Mejia/San Francisco Chronicle.

Of the six homes, 420 Voelker comes closest to embodying the California dream of the house that can see your family through to a better, richer life.

My father’s parents, Tom and Frances Mathews, bought the house new for $15,000 in 1952. Today, the place is not much bigger—they added one small bathroom, a simple deck, and a tiny den—but could be worth $2 million. And that’s not because of anything special that my grandparents, a civilian Navy employee and a public schoolteacher, ever did. It’s because they had the dumb luck to buy a house in a region that would become the world capital of technology, Silicon Valley.

Of course, my grandparents’ lucky circumstance was based on another, more disquieting one. For 40 years, Californians have let houses rule our state. Since 1978, we’ve organized our governance around Prop 13, which limits taxation and centralizes government power—all in the name of keeping property taxes low. But Prop 13 has raised the costs of housing for newer homeowners like me, cutting into the amount of money we have to maintain our houses.

My grandparents did not have to leave their house, and they also had the foresight to put it in a family trust, allowing my father and my uncle to inherit it cheaply. Indeed, 420 Voelker—all of 1,230 square feet—is by far the most valuable thing that anyone in my family owns.

But, with the house paid for and the property taxes so low (under $1,700 a year), 420 Voelker sat empty for most of the last decade as my grandmother spent her final days in a board-and-care home. My parents and I visited as often as possible, but it felt like a sin: an empty house in a Silicon Valley where people are desperate for any housing at all.

The place also grew weathered. The heating system sometimes didn’t work and the apple trees under which we spread my grandfather’s ashes died, leaving the backyard barren. The path down to Laurel Creek eroded so that my kids couldn’t climb down and play with toy boats in the water, as I once did.

I would encounter similar decay as I visited the five other houses. California homes and dreams are much like the American republic.

They require constant vigilance.

255 BENNETT AVENUE, LONG BEACH

Few houses better mirror this state’s sudden shifts in culture and lifestyle than the Long Beach home that my paternal great-grandparents, Raymond and Rebecca Corcoran, paid $8,000 to have built on Bennett Avenue in 1935.

Originally, the Corcoran home was a one-story white colonial, with three small bedrooms, two bathrooms, and a living room and dining room, on one of the higher spots in Long Beach’s Belmont Heights district. Breezes from the ocean, about a mile away, cooled the house even on the hottest days.

Raymond and Rebecca were Southerners (he from Charleston, she from Norfolk) who had traveled the world with their four children—two boys and two girls (including my grandmother, who would settle in San Mateo on Voelker Drive)—to wherever the Navy sent them. When Commander Corcoran retired in 1933, he looked for a place big enough for his family and small enough to afford on a Navy pension. Belmont Heights was a middle-class neighborhood mixing small stores, churches, single-family houses, and small apartment buildings. That mix made the neighborhood resilient and accounts for its attractiveness to this day.

The house at 255 Bennett was always full—of the Corcoran children, grandchildren, and their many associates; of books; and of furnishings picked up during Navy postings in China, Hawai‘i, and Boston. When Raymond died unexpectedly in 1950, it wasn’t clear whether Rebecca—or Great Gram, as we called her—could afford to remain on a modest income. But she did, by living simply, maintaining a robust sense of humor, and investing her meager income conservatively. She never had a TV or a car; she rode her bike to the grocery store and took the bus to church. When she really needed a ride, she would get one from her wisecracking friend Daisy, who drove even though she was legally blind.

In 1981, Great Gram became too frail to keep up the house, and so it was sold. The place would never be the same—literally. New owners, who had two young kids and wanted more room, undertook renovations that added a second story and a lap pool, which replaced the driveway and the backyard. Over the years, the small colonial became a two-story, six-bedroom Santa Fe occupying 4,400 square feet of the 6,500 square foot lot.

This very different house is much more valuable—real estate sites suggest $2 million—but its upkeep has weighed on a succession of owners.

At the same time, the Corcoran house is characteristic of a California where homes have gotten larger even as families have grown smaller. It’s an ironic example of how our dreams and our housing can work at cross-purposes. A state so short of housing in some places has more than enough space in others.

When I visited this fall, the house’s current owners, Dennis and Jennifer Richey, were struggling through the end of a very difficult renovation. The results looked beautiful—the place was a better fit for the retired couple. The Richeys have the house to themselves, each with a den to which they can retreat to get things done.

As I walked through 255 Bennett with them, we talked about the few details that remain from the original home—a front bay window, a couple bedrooms, and a secret trap door in one closet that my great uncles, as boys, used for hiding in the basement.

We were rattling around in the twilight zone between an older California dream and a newer one, and Jennifer volunteered that her “woo woo” friends have detected a woman’s presence in the house, the occasional shadow moving through a door.

“But it’s a kind haunting,” she says.

The Richeys are both Southern Californians—she’s from Glendora, he’s a Long Beach native—and they sound wistful for the days when homes were less expensive and less taxing. Jennifer tells me that she now rents the condo she owned before she married Dennis to one daughter, while another daughter, a university math professor, rents a one-bedroom in Seal Beach.

“My children can’t buy a house in California anymore,” she says.

34 DAVIDSON STREET, CHULA VISTA

The house at the end of Davidson Street in Chula Vista hasn’t changed much at all, but everything around it is different. Once it was a landmark; now it is a secret.

The house is central to the story of the Boltz family, a branch of cousins on my dad’s side. Indeed, it was once central to Chula Vista. In aerial photos from the 1920s, it was the only house nearby, sitting at one of the city’s highest points and in the middle of a large lemon ranch. You could see it for miles.

Today, Chula Vista, situated between downtown San Diego and the Mexican border, is one of California’s most economically and culturally diverse places. It’s also been among the most housing-friendly and fastest-growing—with 270,000 residents, it’s the state’s fourteenth most populous city.

So, when I met my cousin Carol Boltz Paschoal at the house, I struggled to find it, since it’s hidden behind a dense thicket of fences and other houses.

Carol’s great-grandfather Charlie Boltz, originally from Illinois, bought the ranch in 1908, quickly prospered, and was elected to the first Chula Vista city council in 1911. The original Boltz two-story house on the ranch was picked up and moved into town, where it still stands on Second Avenue.

Around 1923, a new ranch house was built for Charlie’s son and daughter-in-law, Oswald and Mary Boltz, who had been married under a pepper tree on the property, which was lit by Japanese lanterns for the occasion. Carol says her childhood was charmed by time spent at her grandparents’ place. There were pancakes every Saturday morning, epic games of croquet, and patio dinner parties.

Oswald and Mary would live in the house into their 90s; even in old age, Carol’s grandfather played his Steinway piano every day and composed his own waltzes. In the 1930s, they added a sunroom and a tiny back porch, and later a pool, but the house would stay basically the same: 1,880 square feet, with three bedrooms and two baths.

It was the neighborhood that would change. making it part of the cryptic story of urban Southern California, which is constructed on lands that once were part of vast ranches. The lands of the Boltz lemon ranch were subdivided for houses in the 1940s, when Chula Vista, having attracted veterans and workers from Fred Rohr’s new aviation plant, became a much bigger place. Eventually, the ranch house was swallowed up by the neighborhood, including the homes of Boltz relatives. Carol still owns and rents out a house next door.

34 Davidson left the family when two of Oswald and Mary’s three sons died of cancer in middle age, and the youngest decided to move to Oregon. It was sold for $178,000 to the Pilchen family in 1986.

Marvin Pilchen, a lawyer and real estate developer, was originally attracted by the potential to subdivide the nearly one-acre lot and match the neighboring plots. But the ranch house had a special charm, and the subdivision never happened.

His wife Atsuko Pilchen especially loved the house’s country style. The land reminded her of the lush mountainside where she grew up in her native Japan. A skilled and diligent gardener, she created a new landscape on the large plot and spent considerable time planting and nurturing fruit trees, including a few lemons in a nod to the place’s history. And being in Chula Vista made her daughter eligible for an excellent school.

She and her husband have spent time in other homes, including a high-rise condo in San Diego’s downtown. But 34 Davidson has remained the family’s anchor. Still, the house itself has come to feel small and cramped without the bigger rooms and higher ceilings so common to modern design. Taking care of an older house on a big lot is a struggle for the Pilchens. The hot water heater, the electricity, and the swimming pool have all required expensive fixes. Repairing the gas and water lines proved difficult because they were installed so long ago that the blueprints weren’t accurate.

California housing stock is similar in age to that of the Rust Belt states—and nearly twice as old as that of our Western neighbors like Arizona and Nevada. This is an underappreciated reason why younger families have left California at such a high rate. In other parts of the West, Californians can find houses that are not just cheaper but also younger and stronger—the kind of places upon which you can build a solid future.

Of course, for those of us who remain, our houses’ connections to the past provide meaning. Atsuko remains friendly with Carol, even wallpapering the halls of her house to match Carol’s. Atsuko says she might want to sell; part of the land is entitled for three more houses to be built. But she feels like an extension of the Boltz family. And she would love to sell to someone who can appreciate the home’s history and maintain what both families have nurtured.

Every time I see her, she asks: “Do you think your family would want to buy it back one day?”

830 OHIO STREET, REDLANDS

One house my family does not want back is the tiny house at 830 Ohio Street, in one of the oldest sections of one of the Inland Empire’s older cities, Redlands.

Don’t get me wrong: I love the place. I spent most of my childhood Thanksgivings there. But its long-suffering form is a testament to the toll that the decay of California’s older houses can take on poorer families.

830 Ohio is barely 1,000 square feet, with one bathroom, one decent bedroom, and a small alcove between the kitchen and the backyard that passes for a second bedroom. It’s so close to Interstate 10 that passing trucks seem to shake the place. But it holds a profound significance for my mother’s family: This is the only house that my great-grandmother, Linnie Humphrey, ever owned.

She was from Sooner stock—she bragged she was older than the state of Oklahoma—and during the Dust Bowl she and her young family abandoned the small town of Okemah (best known as Woody Guthrie’s hometown) for California. In San Bernardino County, she and her husband worked in the packing houses, and rented one of the fruit company’s modest homes in an East Highlands section called the Green Row.

But by the 1960s, the citrus business was dying, and she needed a new job and a new place. So she and my great-grandfather Bull Humphrey took out a mortgage to buy 830 Ohio, which was both a few blocks from their Baptist church and from her new job as a cleaning lady at the University of Redlands.

The house was already pretty worn. Public records say it was built in 1932, though fire insurance records suggest it may have been part of an earlier structure. But it was never so full as during holidays, when her huge family—five children, 22 grandchildren, and too many great-grandchildren to count—would visit and sleep on literally every inch of floor. These family members also helped with the house. Her son Shelby put in the toilet and the bathtub, and others pitched in with the gardening, nurturing orange and lemon trees in the big backyard.

The family sold the place after she died in 1995 for $62,500. The new owner kept it up, but then the Great Recession hit the neighborhood hard. By 2009, many homes in the neighborhood were in foreclosure, and owners either lost or sold their houses.

But in California, one person’s bust is another’s boon.

A longtime chiropractor and real estate investor named A.B. “Barry” Lee seized the moment, buying up multiple neighborhood properties cheaply. Among his purchases was 830 Ohio Street.

Lee, who says he is “pushing 93” but looks 20 years younger, is a Redlands native. When I visited him at his former chiropractic office, he said his work didn’t provide enough for his retirement or to support his wife, who was a teacher, and three children. He says his intentions also are charitable; he hands out food in the neighborhood, takes in difficult tenants who come through drug courts, and provides homes to a local church for their social work.

He built his small Redlands real estate empire—48 rental homes, he says—following the classic 1920s financial book, The Richest Man in Babylon. Author George Clason wrote: “Money is the medium by which earthly success is measured. Money makes possible the enjoyment of the best the earth affords.”

Lee’s dozens of properties, concentrated in just a few blocks, helped shift the neighborhood from a place of homeowners to one of renters, reflecting broader changes across California. Between 2006 and 2014, the number of owner-occupied units in the state fell by a quarter million, while the number of renter-occupied units increased by 850,000. Homeownership statewide dropped to its lowest rate since 1944.

Surveys show most of these new renters lived in single-family detached homes like 830 Ohio. Housing dreams die hard, and visiting 830 Ohio in its new role reminded me of the suffering that Californians will endure because of our devotion to housing. We tolerate the nation’s worst commutes to hold onto the grail of a house, and let enormous shares of our income get swallowed up by rent that might otherwise go to our health or education.

I twice visited the current tenants: a married couple, Louis and Destiny Moore Hernandez, and their two sons, ages 12 and 5, both of whom sleep in that alcove behind the kitchen. Destiny pulled out a thick stack of photos showing rat and roach infestations, and records documenting her exchanges with Lee and the gas company over a persistent leak. I myself tripped over a loose heater grill in the living room floor, which is covered with a wood plank for now. The house has a window A/C unit, but is cold in the winter months because they are afraid to turn on the gas.

“It feels like the house is going to fall apart,” says Destiny.

When I asked Lee about these conditions, he said the family are good tenants who pay their rent, and he appreciates that they push him to fix things; too many tenants never report damage, he added. And the family says they appreciate Lee dropping the rent from $950 to $750 because of the house’s deficiencies.

While it’s nice that everyone has figured out an accommodation, this doesn’t solve the real problem: the faltering conditions of this house and so many in California like it. What’s worst about our aging houses is how much we still need them. While 830 Ohio is part of Lee’s earthly success, it is even more precious to the Hernandez family.

Louis, 54, a former prizefighter, and Destiny, 36, both subsist on $689 monthly disability checks; the $750 rent consumes more than half of their income. Still, they remain. The house is a place where they can stay cool in the summer, with an above-ground pool that they bought at Kohl’s and are slowly paying off at $27 a month. And it’s a place to return to after Destiny, an expert at finding cheap ways to entertain her boys, takes them to certain games of the minor league Inland Empire 66ers in San Bernardino, where 50-cent admission and discounted hot dogs give the family a night out for just $10.

Louis and Destiny say that the house, for all its problems, holds the promise of some stability so their boys can achieve their dreams. “We could be worse. We’re all together as a family,” Destiny says. “And we’re not on the street.”

But circumstances on Ohio Street could just as quickly shift to displace the Hernandez family. On the other side of Interstate 10 is the lovely and expanding historic downtown. It may only be a matter of time before redevelopment comes and 830 Ohio, and its Redlands neighborhood, are no more.

1306 GARDEN AVENUE, MODESTO

My next stop was Modesto, where my great uncle Shelby—who installed the bathroom at his mother’s place on Ohio Street—moved with his wife Doris and 10 children after World War II. Over the next few decades, they rented 17 different places—until 1983, when they bought a tiny home (just 720 square feet) at 1306 Garden Avenue for $30,000.

Shelby’s son Wes put in a lovely deck, and the whole family helped Shelby—who had a tree service but whose alcoholism often landed him in trouble—keep up the place. After he died in 2005, they managed to sell it for $240,000.

But then the Great Recession hit with full force. 1306 Garden went into foreclosure and the Bank of New York seized it.

In 2009, the bank sold it for just $44,000, meaning that 1306 Garden lost 80 percent of its value in four years.

On Modesto’s west side, there was little to cushion the recession’s blow, in part because this neighborhood is an unincorporated pocket of Stanislaus County, outside the city’s limits. Streets here are a hellscape of ruts and holes, there aren’t any sidewalks, and public services are less than robust. In the middle of the night, young people race motorcycles and cars at dangerous speeds with impunity. It’s a neighborhood where some people complain the county sheriffs are slow to arrive while others say they fear ICE.

I never loved 1306 Garden. It was a small place that gave a rough man a bit of stability. But now it’s something else. A decade after the crash, the house and the neighborhood still haven’t fully recovered. And that gives it a precarious feeling.

The man who bought the house in 2009, and still owns it, isn’t rich. He is a local warehouse worker named David Gomez, age 54. He tells me that the collapse of the housing crisis, in combination with the federal tax benefits for homeowners, provided a very rare investment opportunity for a middle-class person. During the crash, he purchased five other homes around Modesto, one of which he lives in. When I drove by each of them, they were among the better maintained in their areas. But it has not been easy for him.

Gomez’s tenants can come and go fast. When I visited 1306 Garden, he had just replaced renters who had filled the yard with garbage and, neighbors say, a trailer. People living in trailers—essentially subletting yard space from tenants—is common in the area, as a way for poor people to make a little money and for even poorer people to stay off the streets or out of homeless encampments along the river. This pocket of Modesto’s west side has become a neighborhood of last resort.

Four people live in the house now, which by official standards—there should be no more than one resident per room—is too many. California has an overcrowding rate of over 8 percent, more than twice the national average of 3.4 percent.

And then there is the shit. The house sits next to a Modesto city wastewater treatment plant, which is now expanding to butt up against the property. A city sewage line runs under the house. Gomez says the city contacted him about taking the house by eminent domain, but, for now, has decided against it. He’s not disappointed. The house is worth only half of what it was when Uncle Shelby died. But it’s still three times more valuable than when Gomez purchased it.

Gomez is pleased with the new tenants so far; they even took the initiative to put in a back fence. But maintenance, which he handles himself, is a constant struggle. “You’re dealing with dirty people in dirty places and with code enforcement,” he says of owning California houses. “I’ve learned you have to be strict down the line.”

310 NORTH OLYMPIA PLACE, ANAHEIM

How does a neighborhood hold the line and stay middle class in an increasingly unequal California? A third house from my mother’s side of the family offers two answers: inheritance and immigration.

My Grandma Edith’s old house sits in a cul-de-sac just off the long corridor of State College Boulevard, which connects Angel Stadium with Cal State Fullerton.

This three-bedroom, 2,000-square foot split level, built in 1957, was a very hard-earned piece of the California dream when she bought it for $18,900 in 1963. Edith had come to California from Oklahoma in her teens and found work on the assembly lines of Southern California’s military-industrial complex. Through the 1950s, she and my grandfather lived with my mom and uncle in Hawthorne, near LAX, while she worked at North American Aviation in El Segundo.

When aerospace moved to Orange County, she moved with it. She would eventually install electronics on the space shuttles for Rockwell. After she bought the Anaheim house, she made one major addition: enclosing a rear porch, turning it into a rec room, and decorating the walls with photos of the shuttle and its astronauts, to whom she was devoted.

She wasn’t as lucky with husbands. She divorced my grandfather and a third husband. Her beloved second husband Jerry, an auto mechanic who took me to my first baseball game, would die of brain cancer in 1980, just seven years into their marriage. I visited the house often; on Christmas Eve, we would stay with her and go to Disneyland. My brother and I played baseball on the cul-de-sac with neighborhood kids.

A smoker, Edith died of lung and brain cancer in 1991 at age 65. The house was sold by our family for $210,000 in 1992, and changed hands a few more times before going into foreclosure in the Great Recession.

But this cul-de-sac did not collapse. Some of the kids I had played with moved back into their parents’ homes, renewing the neighborhood.

And in 2011, when 310 Olympia was put up for auction at a local hotel, the house had the good fortune to be purchased for $296,000 by a dentist named Quan Pham.

Pham escaped from his native Vietnam by boat after the war’s end, landing in a refugee camp in Indonesia before immigrating to Australia and then to California, where he did his training. For many years, he practiced in Orange County, but could not afford a home there. So he commuted each week from his residence in Las Vegas, relentlessly saving until the Great Recession created an opportunity in Anaheim.

Pham told me he bought the house because of my grandmother’s old rec room, which a previous owner had expanded to two stories tall. That owner had used it to display his hockey trophies. But Pham turned it into a Vietnamese dance hall, with Asian art filling glass cases, a dance floor, a bar, and a stereo and microphone system so he and his wife and their friends could sing and dance. It’s also a home for his African gray parrot, Simba, who speaks English and Vietnamese and knows one Spanish phrase: “Yo no quiero Trump.”

Pham, who at 58 is recently retired, is a very active man—he plays every sport and kitesurfs, and says he might expand the giant room to accommodate indoor badminton. But his greatest magic lies in the garden.

On the home’s 7,980-square-foot lot, he has created an outdoor space so elaborate that it took him nearly two hours to give me a tour. First, we saw chickens (he likes Malaysian chickens, who walk more upright) and the orchids he’s raising in a makeshift greenhouse. Then he took me through his dozens of exotic, tropical trees, including multiple varieties of mangoes, mandarins, pears, and apples. He’s especially proud of his sapodilla trees. He picked the Morena sapodilla fruit and cut it up for me; it tastes like a brown sugar-covered pear. He even raises sugar cane along the short driveway, so he can open it up and eat the sugar directly, like he did as a child in Vietnam.

He had one pointed message for me: Houses are too often treated only as investments. The real value of houses is what we can make with them. He asked how much my grandmother paid in 1963, and when I told him $18,900, he did the math. The house is worth around $600,000 today, but “if she had put money in the stock market, it would be $4.4 million now.”

I told him how much my grandmother, herself a gardener, would have loved what he’s done with the place. He thanked me and said, “If you live in California and you have the time, you can grow many different things.”

420 VOELKER DRIVE, SAN MATEO

Back in San Mateo, my uncle Jim Mathews, 72, and his roommate Gina Cooper, 45, are figuring out how to grow by combining their dreams in the old house. California housing is usually too challenging to handle alone. It takes more than one generation, and sometimes more than one family, to keep a home here.

Gina and her son Dante used to live in her mother’s house in Belmont, just south of San Mateo. But after her mother died, Gina lost her residence. By 2012, she and Dante were homeless, moving through the booming area’s shelters for about a year.

“When you become homeless and you’re looking at your 12-year-old, that is the most horrible feeling—you’re responsible, and you’ve reduced his life to homelessness,” she says.

Eventually, Gina found work for a shelter she’d stayed in. She was coming to the end of her term in a non-profit’s temporary housing when she gave a talk about being homeless at my uncle’s church.

Gina and Dante needed housing. Jim required a walker and needed help getting around his condo. So they formed an arrangement called “house sharing,” in which a homeowner brings in a roommate who handles some house duties and receives a reduced rent.

In 2016, as my grandmother was dying, Jim retired from the local school district, where he ran computer labs, and decided to move out of his condo and back into my grandparents’ house at 420 Voelker. Jim asked Gina, Dante, and their dog Kona to move with him.

Essentially, they all take care of each other.

Gina helps out with home expenses, at about $1,000 a month. Gina and Jim each have their own bedroom and Dante, now 18, sleeps on the couch in the living room. Gina makes coffee each morning, changes Jim’s sheets when he’s at church on Sundays, and cooks dinner six nights a week. She’s improved his health; when I joined them for dinner, I was shocked to discover my hamburger-loving uncle eating kale.

Jim says, “I’ve been single all my life, and I never really had a female influence over how I was living. I wish I had figured out to do this 10 years ago.”

Meanwhile, the stability of home has allowed Gina to secure a job and begin a career with the city of San Mateo while continuing her education. “Once I found Jim, I could take risks, and try a new job,” she says.

This spring Dante graduated from Hillsdale High—my father and uncle’s alma mater—and is now in a union apprenticeship program for mechanics. Gina and Jim say their daily conversations are crucial to their health; they are each other’s sounding boards.

Gina tells me she has saved money and put herself on a list for a city program that helps public employees buy below-market-rate housing. The waiting list is about two years long.

Programs like this can be valuable, and they represent one common official solution to this state’s difficulties with housing people. But policy often moves too slowly to respond to our housing realities.

During the recent months I spent with these homes, I became convinced that Gina and Jim’s spirit of flexibility is what California’s homes and dreams need now. A state built on the fusion of peoples and cultures and technologies must apply its powers of mixing and creation to its old housing stock.

This will require a new California dream of housing renewal—and a social transformation. Our laws, finances, and customs make it so hard to transform our homes that too many of us become prisoners in them. And our own preoccupation with “preserving the character” of our communities needs to be exposed for what it is: a sorry defense for a status quo of housing decay.

If Californians’ housing and dreams are to remain intertwined, then we need to rethink the very idea of home, with the goal of ensuring that our changing dreams and our shifting needs, not our aging houses, come first.

I thank Gina for dinner and take a look around. The memories flood back—of painting the side fence with my brother, of long talks with my grandmother, of squeezing my grandfather’s old Cadillac into the small garage.

The house is nicer now than when my grandmother, who never cared for housework, was alive. But it is 66 years old, and I notice the broken garage door and other small repairs to be done.

As I leave, I feel a familiar California heartbreak: to look upon a house you love, and to know it will never love you back.

Send A Letter To the Editors