The Postcards That Captured America’s Love for the Open Road

From Mid-Century Until Today, “Greetings From” Postcards Have Combined a ‘Fantastical View’ of the Country With Car Culture Obsession

The most prolific producer of the iconic 20th-century American travel postcard was a German-born printer, a man named Curt Teich, who immigrated to America in 1895. In 1931, Teich’s printing company introduced brightly colored, linen-textured postcards that remain familiar today—the sort that trumpeted “Greetings from Oshkosh, Wisconsin!” “Greetings from Rawlins, Wyoming!” or “Greetings from Butte, Montana!”

The most prolific producer of the iconic 20th-century American travel postcard was a German-born printer, a man named Curt Teich, who immigrated to America in 1895. In 1931, Teich’s printing company introduced brightly colored, linen-textured postcards that remain familiar today—the sort that trumpeted “Greetings from Oshkosh, Wisconsin!” “Greetings from Rawlins, Wyoming!” or “Greetings from Butte, Montana!”

Like so many industrious strivers who came to the United States at the close of the 19th century, Teich pursued his postcard business as a means of building a life for his family (and getting rich while he was at it, if he lucked out). But Teich’s American Dream also did something more. His linen-style postcards depicted an optimistic view of America, creating a unique record of national tourism and documenting the U.S. landscape from its smallest towns to its grandest natural wonders. The cards—and Teich’s runaway success selling them—also reflect an era when a boom in highway construction and an uptick in auto sales were changing the way Americans worked, played, vacationed, and communicated with one another.

Linen postcards, named for their embossed linen-like texture, were tremendously popular in the United States during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. There is no exact count, but deltiologists—people who study postcards—estimate that publishers developed over 150,000 different images and printed millions of copies. Cards typically depicted American scenes, venues, and businesses. They sold for a penny or were given away by local entrepreneurs or at tourist destinations.

Their runaway popularity was fueled by the country’s dawning obsession with the automobile, car travel, and car culture. In 1913, the Ford Model T became the first mass-produced automobile to roll off an assembly line; in the following decades, cars became more affordable and ownership rapidly increased. Federal Highway Administration statistics indicate that Americans registered over 22 million privately-owned automobiles in the United States in 1935. By 1952, that number had jumped to almost 44 million.

For as long as Americans could remember, road travel had been a dirty, dusty nuisance on unmarked and rutted routes. But the Good Roads Movement, founded in 1880 by bicycling enthusiasts, brought attention to the poor quality of American roads. Soon, state-based Good Roads Associations formed. They pushed for legislation to fund road improvements and local officials heard the call. In 1913, Carl Fisher, manufacturer of Prest-O-Lite headlights and developer of Miami Beach, formed the Lincoln Highway Association, which conceptualized and eventually built a road from New York City to San Francisco. The Federal Aid Road Act, enacted in 1916, provided the first federal highway funding and fostered the development of a national highway system. Ten years later, construction began for the famed Route 66, also known as the Main Street of America. Completed in 1937, its 2,448 miles of asphalt carried car travelers from Chicago to Los Angeles, crossing three time zones and eight states.

All these miles and miles of new roads allowed families to craft journeys to destinations such as the Grand Canyon, Arizona; Mount Rushmore, South Dakota; or the tropical shores of Florida. Itineraries were planned and maps carefully marked. Americans—enamored of the newfound freedom offered by personal vehicle ownership and thrilled to discover new and marvelous places—packed their suitcases, loaded their cars, and took off.

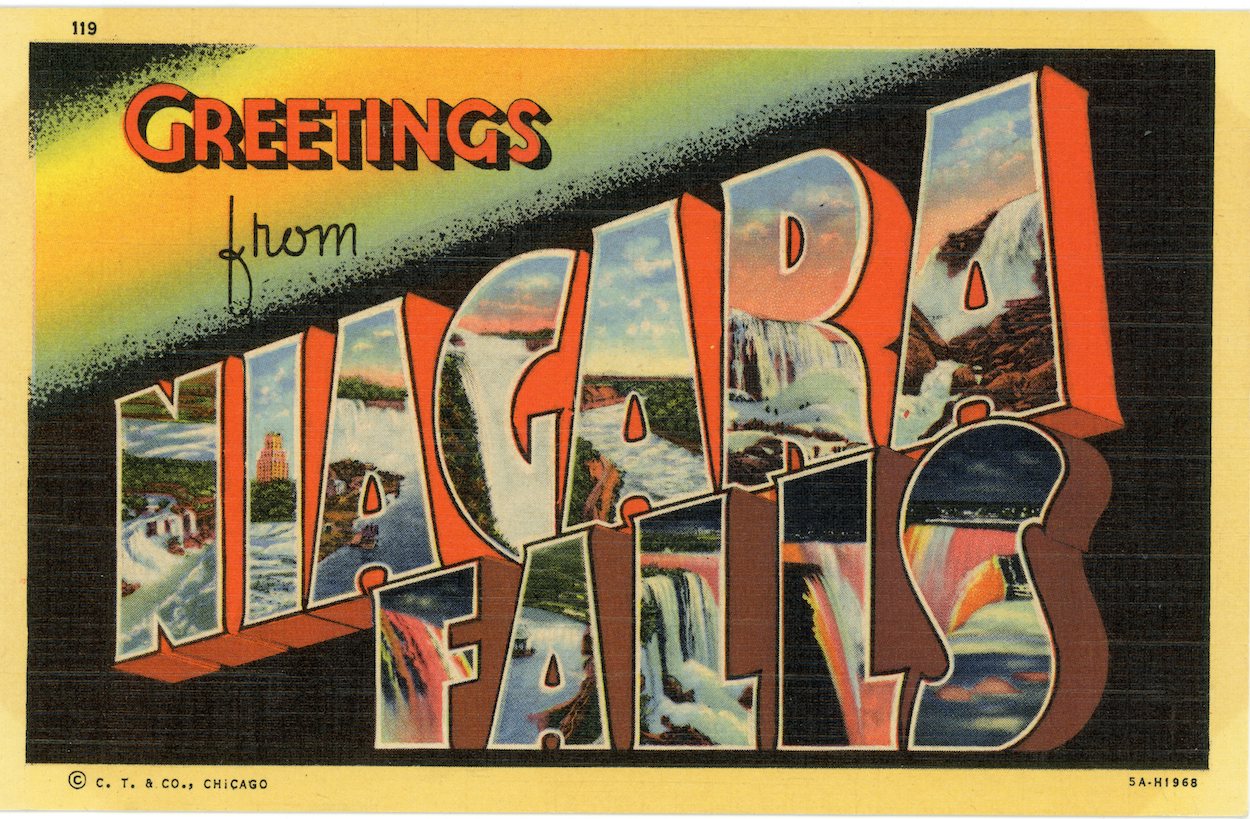

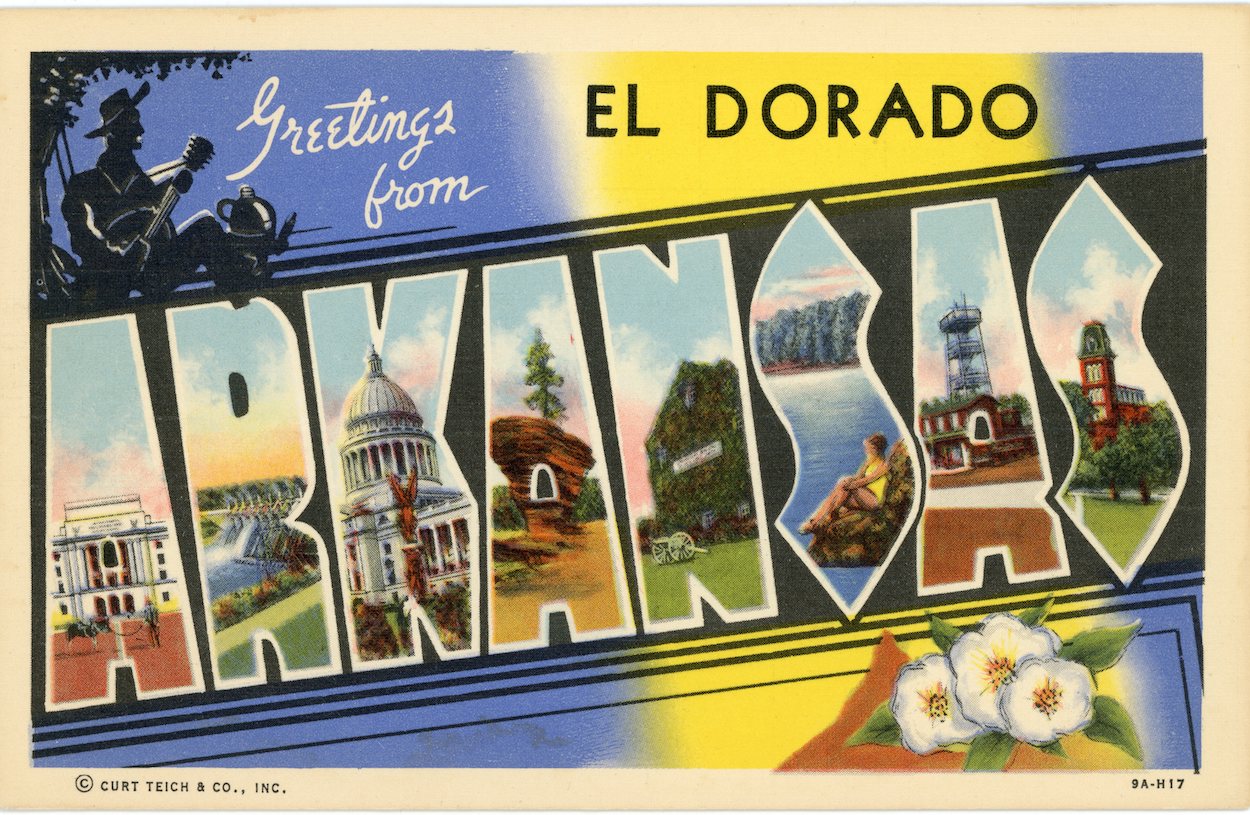

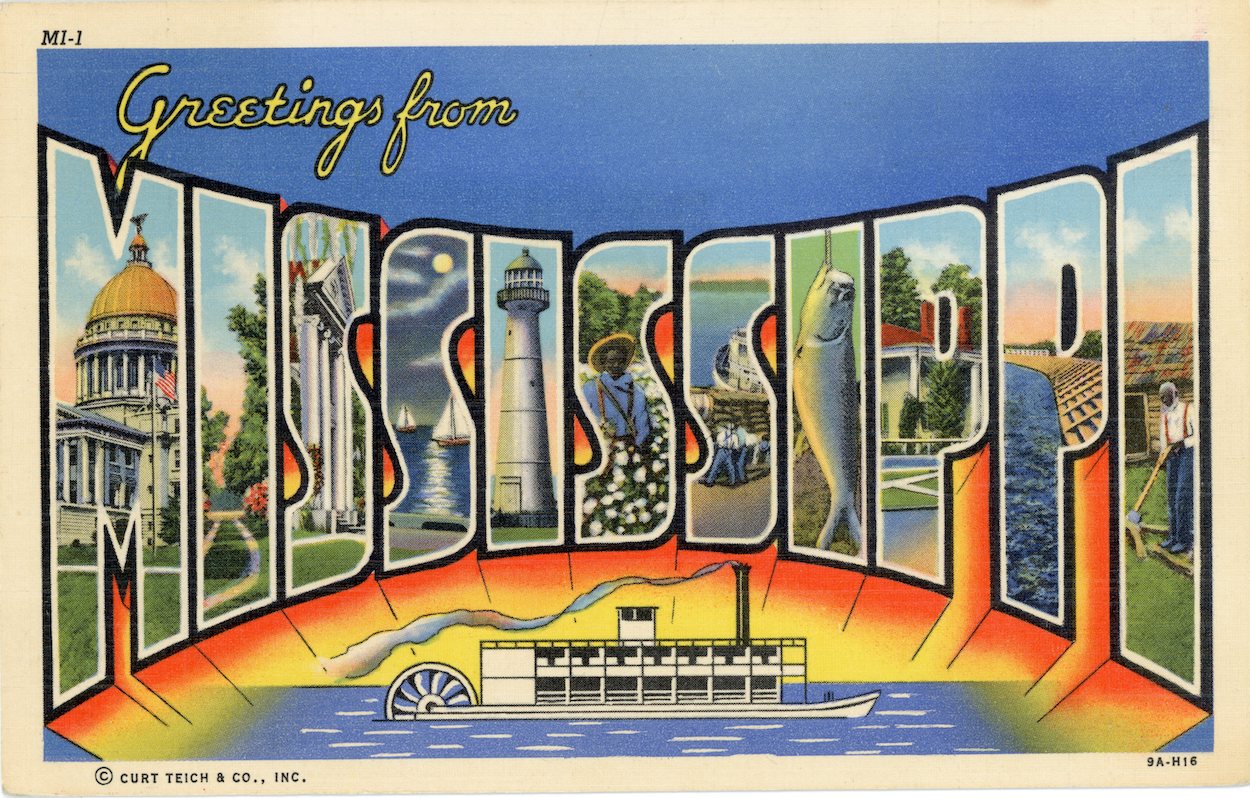

Linen postcard publishers didn’t miss a beat, photographing and printing thousands of images along those highways. Picture postcards weren’t new when Teich founded his company in 1898; they had emerged in France, Great Britain, Germany, and Japan in the early 1870s and had quickly become very popular. But the linen-type postcards Teich (and eventually his imitators) produced were distinctly American, rendered in an opulent style, depicting wonders from the corner luncheonette to Niagara Falls. Teich’s offset printing technique lavished cards in saturated colors and used airbrushing and other effects to reduce unwanted details. The visual result was a fantastical—and enticing—view of America. Postcard images of sun-dappled, sinuous roads captured the spirit and adventure of road travel.

Businesses that depended on tourism saw Teich’s cards as a great tool to attract customers, who found the images hard to resist on the postcard rack at a local drug store, Woolworth’s, or service station. Sensing opportunity, Teich employed a cadre of sales agents to obtain and manage regional accounts, who often photographed sites for postcard production. Teich believed that no town was too small for its local attractions to be made more beautiful by his art department’s color processes. Linen postcards advertised motels and motor courts with clean rooms and radios. Roadside eateries’ cards showed off delicacies: fried clams at Howard Johnson’s restaurants on the East Coast; shoo-fly pie at the Dutch Haven in Lancaster, Pennsylvania; all-you-can-eat chicken dinners at Zehnder’s Restaurant in Frankenmuth, Michigan. Cities advertised hotel accommodations on linen postcards, too, hawking stylish supper clubs with music and dancing, and restaurants with fine dining and cocktails.

One popular format for linen postcards was the “Greetings From” style, which had been inspired by the “Gruss Aus” (“Greeting From”) postcards Teich had known as a young man in Germany. The German postcards featured local views with subdued lettering and a muted color palette; Teich’s American incarnation reflected the popular streamlined aesthetic of the time, featuring the name of a state, city, or attraction—emblazoned in large 3D letters—with miniature images of regional scenes depicted within. Travelers to Miami, Florida could purchase a postcard from the Parrot Jungle, a tourist attraction in an unspoiled tropical forest, with bathing beauties in the letter “P” and parrots in the letter “J.” Drivers cruising along Route 66 in Missouri might select a large letter card containing tiny images of Meramec State Park and scenic bluffs along the Gasconade River, examples of the natural diversity they saw along the highway.

People sent the postcards, spending a penny on postage, home to family and friends. It was an easy way to communicate information, to be sure, but with a twist any Instagram fan today would recognize immediately: an offhand, entertaining visual brag that showed just how much fun the sender was having at a nightclub, hotel, national monument, or natural wonder in some faraway state. The linen-style postcard, with its cheerful utopian imagery, captured the spirit of hope and optimism Americans craved during the Great Depression and World War II—and found during the post-war years.

By the mid-1950s, the Eisenhower administration’s supersized interstate highway system had begun bypassing local and scenic roads, and newly constructed shopping malls led to the demise of Main Street shops. Travelers purchasing postcards embraced a new aesthetic, based on color photography, that included sharp outlines of realistic (and increasingly generic) images on a shiny surface. Production of linen postcards decreased—and so did the sense of optimism depicted in the colorful, air-brushed images they had featured.

Curt Teich died in 1974 at the age of 96. Four years later, his company officially closed its doors. His family donated nearly half a million postcards and artifacts to the Lake County Discovery Museum in Libertyville, Illinois, which began transferring the collection to the Newberry Library in Chicago in 2016. Today, researchers pore over those cards—picturing extraordinary natural landscapes and quotidian small-town scenes—for a glimpse of the past in an increasingly mobile America. When Teich arrived in the United States, did he imagine his company would create such a tangible record of American life? Perhaps not, but his penny postcards, with their picturesque utopian images, harken back to the nascent days of automobile travel and the thrill of discovering the sweeping expanse and profound beauty of the American landscape.

Send A Letter To the Editors