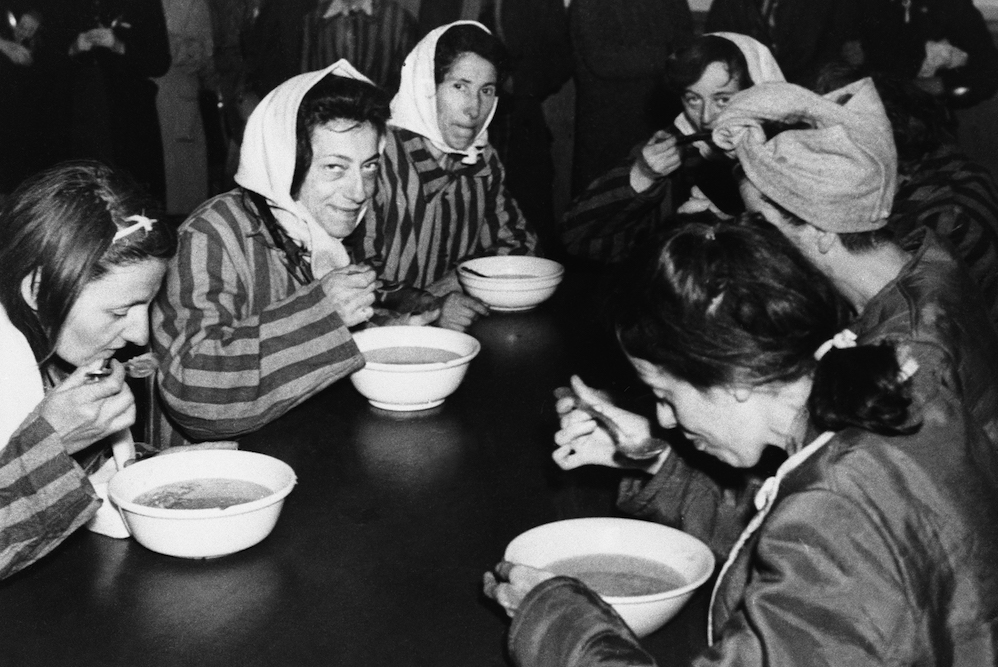

Two weeks after Belsen concentration camp was liberated by the Allies in April 1945, detainees, seen here eating soup, were still considered to be in a “state of starvation.” Courtesy of the Associated Press.

When the Soviet Union sent Dmitri Likhachev to an offshore detention camp in February 1928, the Russian scholar was crammed onto a train car with other prisoners and handed a large cake. His five-year sentence without the benefit of a trial was a gift of the government. The cake came from the university library where he had worked before his arrest. It held no hacksaw to free him, but he would remember the goodbye present for seven decades.

Likhachev was not the only person who recalled gifts of food during detention. While researching concentration camps around the world, I learned that even the memory of food helped sustain prisoners, linking them to distant friends and family and building bonds between detainees. Through interviews, written memoirs, and even archival “recipes,” the way in which imaginary feasts created community in places that were beyond hope came up again and again, revealing how even in its absence, food defines and shapes the most rudimentary forms of society.

Real food, of course, offered more sustenance than reminiscence could provide. But many concentration camp systems failed to feed prisoners enough to survive, and administrators wielded food as a weapon of control. Enduring forced labor as a teenager at Monowitz—part of Auschwitz—Elie Wiesel described hunger reducing him to “nothing but a body. Perhaps less: a famished stomach. The stomach alone was measuring time.”

Though his experiences were horrifying, Wiesel was fortunate enough to have avoided the gas chamber during selection. But extermination through labor—a combination of brutal work and deliberately limited rations—further culled prisoners assigned to the worst work details. Detainees died of gastroenteritis, pneumonia and a host of conditions that easily took hold as prisoners slowly starved to death.

In these conditions, access to additional food was critical. A post working in the vegetable cellar of a camp, such as the one German communist Margarete Buber-Neumann found in the Soviet Gulag in 1939, could provide a way to expand on the watery soup and bread typically allocated to prisoners. Buber helped to keep herself and others alive with stolen food.

Sometimes prisoners were buoyed by food from loved ones, as Likhachev had been touched by the present of a cake. Held with thousands of other suspects at the National Stadium in Santiago, Chile, in fall 1973, Felipe Agüero recounted the joy of receiving a care package in detention, but also how the meagerness of what was sent—a few cigarettes or a little bread, maybe some chocolate—revealed that hard times had come for family on the outside, too.

Where they could not scrounge or steal real food, captives turned to their imaginations. Despite the most desperate conditions, concentration camp inmates routinely spent their fleeting idle moments discussing recipes. At Neuengamme, not far from Hamburg in northern Germany, after work in factories, digging in clay pits, or dragging rubble out of bombed-out streets, during the only time they had to try to remain human, detainees talked about their homes and families, their previous lives that had vanished forever, and their favorite meals. They had little else to live on. As the war dragged on, life expectancy for new arrivals at Neuengamme dwindled to 12 weeks.

Shared recipes preserved from this era of camps found improbable publication with In Memory’s Kitchen: A Legacy from the Women of Terezin. This 1996 compilation included a series of recipes that had been collected in the Nazi camp of Theresienstadt. A detainee named Mina Pachter had gathered recipes from inmates in the camp and given them to a friend to carry to her daughter, if he found a way to survive. After Pachter died, the collected recipes took more than 20 years to make their way into the hands of her daughter in New York, who eventually decided to publish the instructions for making such dishes as chicken galantine, liver dumplings, stuffed goose neck, asparagus salad, plum strudel, and chocolate torte.

The book was condemned by some who called it “sick,” wondering if cookbooks from Auschwitz or Treblinka would soon follow. The recipes themselves were often missing key ingredients or had completely mismatched measurements that made them useless. Others lauded the publication as Holocaust literature rather than a literal cookbook, a memory of how detainees consoled themselves in humanity’s darkest hours.

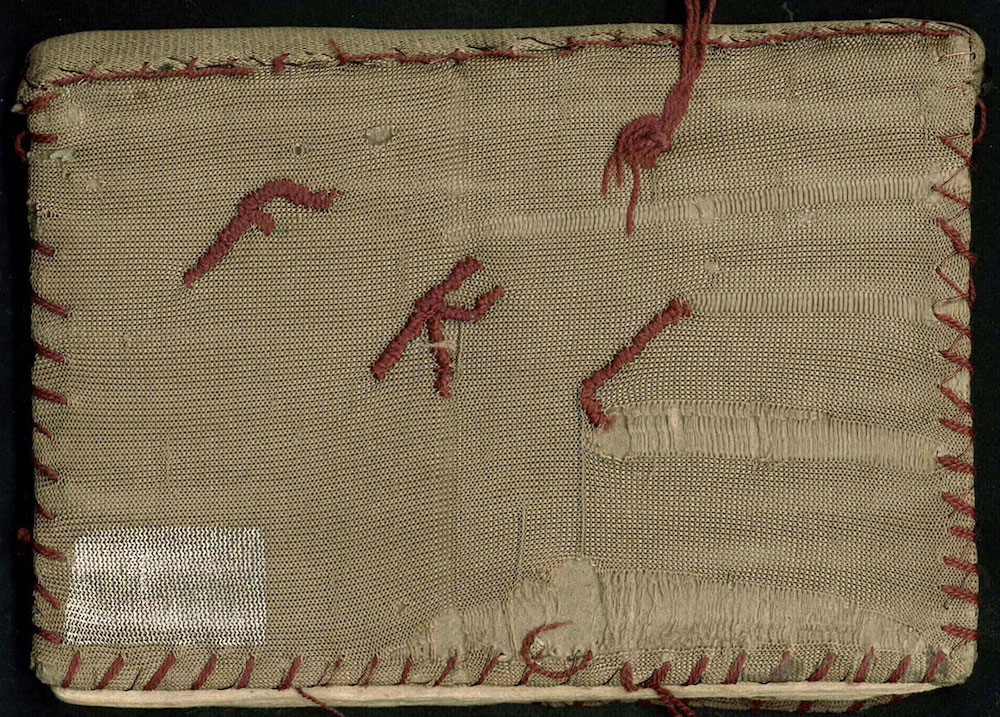

More cookbooks emerged over time, but not necessarily for publication. At the age of 12, in the women’s camp at Ravensbrück in Germany, Nurit Stern listened to adults commune with each other. “Hungry people can only dream about food,” she explained in 2016. “I was a child. I didn’t know anything about cooking. I memorized the recipes and wrote them down.” The small notebook she cobbled together out of stolen materials ended up enshrining the women’s recipes—chopped liver, goulash, stuffed cabbage rolls, and cholent with kishke—for posterity in Yad Vashem’s archive. Stern explained the role the recipes played for people struggling to maintain their humanity. “These women used their memories and imagination to memorize this most basic experience… Many chose this way to protect their sanity.”

Nurit Stern made this recipe book as a child to record the recipes she heard adults discussing in the Ravensbrück camp. (The letters “FKL” stand for Frauenkonzentrationslager, or “Women’s Concentration Camp.” Courtesy of the Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection.

While recipes and fantasies about unlimited food helped detainees endure the everyday horrors of the camps, the issue of food has also been used as a tool of propaganda to keep the public from sympathizing with detainees.

During internment of Japanese-Americans in the Second World War, a series of allegations about detainees being “pampered” in camps centered around food. One New York Times headline from May 1943 reads, “Wyoming Senator Asserts Japanese Go Unrationed and Have Vast Stores of Food.” While much of the U.S. was using ration tickets to buy food, Senator Edward Robinson accused detainees of hoarding meat and mayonnaise in the camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, claiming they had enough supplies on hand to feed the camp population for “three years, seven months and fourteen days.” The actual historical record on Heart Mountain, not surprisingly, contains references to late food shipments in insufficient quantities.

The very idea of food for detainees remains a highly politicized subject—partly because detention is seen as a way to punish a targeted group, even when governments deny that punishment is the goal. In 2005, a group of political activists who saw reports on American torture as “military bashing,” assembled a book of their own: The Gitmo Cookbook. Gathering recipes for halal meals including curried eggs, tandoori chicken, and Lyonnaise rice that the Navy had developed to serve those held on the Cuban base, the book’s authors aimed to show just how well detainees in American custody were treated. Nearly a decade would pass before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Torture Report verified many of the worst accusations of torture and abuse of detainees.

Why do propangandists feel the need to ascribe gluttony, extravagant meals, or hoarding to detainees? Food is so basic to existence that our common need for it provides the root of our ability to empathize with one another. This empathy lies at the heart of how society functions. When propagandists want to show that those held without trial do not deserve empathy, or are abusing it, they use stories of lavish food as a way to further isolate detainees from society.

A similar principle is at work when prisoners take comfort from the shared ritual of imagined meals. Written and spoken recipes offer a performance of survival when survival is uncertain. They provide detainees the kind of social interactions that camps are typically created to prevent. Sharing the desire for a specific food prepared a specific way further takes the animal impulse to survive and transforms it into art, reasserting the shared humanity of both the teller and the listeners.

Food offers those closed off from society a way to resurrect its ghost behind barbed wire. In China’s Xihongsan Mine labor camp in 1961, prisoner Harry Wu recalled “food-imagining parties.” Inside stone barracks atop a tamped mud floor, Wu described how one person would take a turn, and the next night, another detainee would reciprocate.

Wu was himself altogether ignorant of cooking but joined in, using invention where experience failed him. Before going to sleep, inmates lovingly narrated the creation of a favorite dish, sometimes a secret recipe from childhood or something specific to their home province. “We would explain in detail how to cut the ingredients, how to season them, mix them, and arrange them on the plate.” Once the dish was ready to eat, the detainee would first describe the smell, and then the taste. Decades later, Wu recalled the spell that was cast. “Everyone,” he wrote, “would listen in silence.”

Send A Letter To the Editors