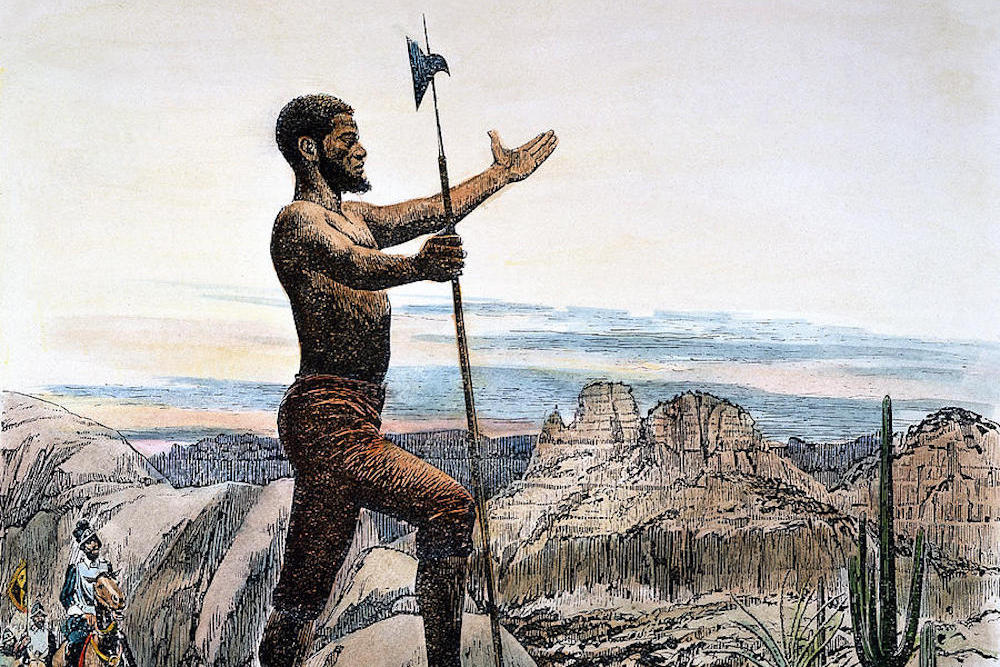

Estevanico (c. 1500–1539), a Moroccan who was sold into slavery but later became one of the first native Africans to explore the present-day continental United States, traveling on Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s expedition across the Southwest. Courtesy of the Texas State Historical Society.

“The first white man our people saw was a black man,” wrote historian and Pueblo native Joe Sando in Pueblo Nations.

Sando was referring to Esteban, an African who became the first non-Indian to enter what is now Arizona and New Mexico in 1539. Esteban made his way to the Southwestern corner of the what is now the United States 46 years before the first English-speaking colonists crossed the Atlantic.

African involvement in America’s history goes back further than most Americans realize. Although history has mainly forgotten them, an unknown number of Spanish-owned black slaves escaped into the East Coast wilderness from Spanish ships in the early 1500s. Black slaves and free Africans also went with conquistador Juan Ponce de León when he sailed to Florida in 1513 and 1521.

But Esteban stood out as a pioneer in the Southwest and North America. The Spaniard Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca first brought attention to Esteban in his 1542 book, known as La Relación. The book described the invasion of Florida by 300 or more Spanish conquistadors in 1528, their defeat by Florida’s natives, and their escape across the Gulf of Mexico in five crude boats that eventually wrecked on the Texas coast near today’s Galveston.

Only about 20 people from the expedition survived the first winter in Texas. Twelve of those survivors visited Cabeza de Vaca, who was ill in a Karankawa native village. Among them, Cabeza de Vaca reported, was Estevanico.

The term Estevanico was a demeaning slave nickname for the man most historians believe was found in Morocco and sold into slavery on the Iberian Peninsula in the 1520s. His Spanish slave owner had named him Esteban.

Cabeza de Vaca called Esteban by his nickname seven times in the second half of his book—elsewhere referring to him only as el negro. But mention of Esteban in any form acknowledged that the African had become accepted by the few surviving expedition members. Weeks later, only five were still alive, and they would be enslaved by bands of Karankawa Indians for the next five years.

Not many slaves have seen their masters also enslaved. With Indians in charge, Esteban’s Spanish companions toiled at his side.

In the fall of 1534, after multiple escape attempts, Esteban and three Spaniards with him, including Cabeza de Vaca, managed to flee their captors. They would walk for a distance they could never have imagined through western Texas and across northern Mexico. The late historian John Upton Terrell described their trek as “the most remarkable overland journey in the history of American exploration.” Eventually they turned south and ended up in Mexico City on July 23, 1536—having traveled eight years and at least 3,500 miles since landing in Florida.

Cabeza de Vaca portrayed himself as their heroic leader. Yet his own account makes it obvious that whenever the Spaniards needed help with the Indians, Esteban was the man they depended on.

The route toward the western side of the continent took them to numerous tribes with different languages. Throughout their journey it was Esteban who led the way, going ahead to introduce his three Spanish companions to native villagers, building goodwill with his ability to speak native languages, his fluency in the continent’s Indian sign language, and his personality. They were welcomed by tribe after tribe as they developed some fame; they were seen by some as medicine men who could heal Indians of ailments such as headaches, dizziness, cramps, and pain.

Cabeza de Vaca admitted that he and the other two Spaniards rarely spoke to natives. They depended on Esteban to communicate because he quickly learned languages. Their aloof attitude ensured Esteban’s status as the group’s most important member.

In writing about their cross-continent ordeal, Cabeza de Vaca gave credit to God for “opening roads for us through a land so deserted, bringing us people where many times there were none, and liberating us from so many dangers and not permitting us to be killed, and sustaining us through so much hunger, and inspiring these people to treat us well.” But in all these things, Cabeza de Vaca could have credited Esteban as God’s instrument.

“He is the least discussed yet most intriguing character in the entire expedition,” the historian Paul Schneider has observed.

Esteban’s leadership, language skills, and friendship with the natives were why Viceroy Mendoza picked him to guide the 1539 expedition to find rumored rich Indian cities north of Mexico.

That was the oddest expedition Spaniards ever launched. It consisted of hundreds of Mexican Indians who had been promised an end to slavery if they assisted. And it was led not by conquistadors but by a Franciscan friar guided by the African Esteban.

On that expedition, the slave nickname fell out of favor. Antonio de Mendoza, the Spanish viceroy of Mexico who appointed Esteban as the expedition’s guide, and Marcos de Niza, a French friar on the expedition with him, referred to him only by his name of Esteban in letters and reports they wrote in 1539. Esteban is the only slave known to have been referred to by his Spanish name in letters to Carlos I, the king of Spain at the time.

Esteban arrived at the southwestern-most village of the Zuni tribe in New Mexico in May 1539, more than a hundred miles in front of Friar Marcos, who’d sent him ahead to find the way northward.

It was at that village known as Hawikuh or Hawikku that Esteban vanished. Conventional wisdom declares that Zunis killed him. But did they? That supposed death is based only on assumptions, with no European ever witnessing Esteban’s arrival or fate. Perhaps the Zunis let him live on with them or, as one of their oral histories states, exiled him back to Mexico. Perhaps he kept moving north. Regardless, he disappeared from the historical record.

Esteban, however, is not forgotten. Historian Joe Sando has written about how each annual feast day at Jemez Pueblo includes one or more figures representing Esteban with their faces painted black and wearing curly sheep pelts on their heads. All the existing New Mexico pueblos share some knowledge about Esteban.

There will never be proof about his fate. If the Zunis spared him, perhaps blood still runs in some Puebloan veins from the African slave who poet-conquistador Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá described as El grande negro Esteban valeroso—“the big, black, brave Esteban.”

Send A Letter To the Editors