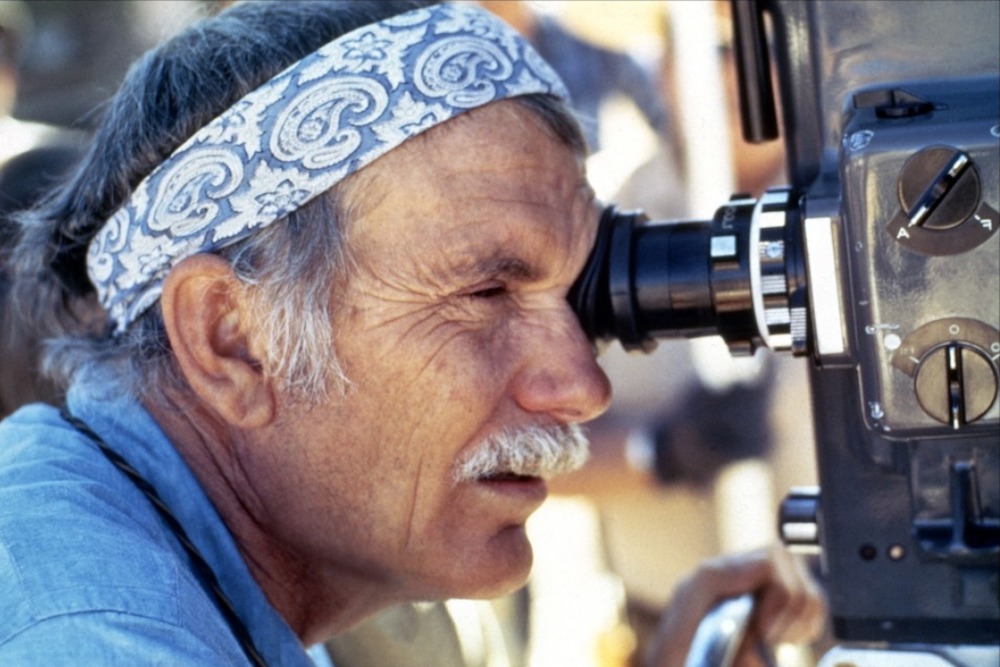

Director Sam Peckinpah behind the camera on the set of The Wild Bunch, where he worked long hours, drank no more than beer, and stayed in his chair even though he was bleeding through his jeans. Courtesy of Flickr.

Sam Peckinpah was many things: brilliant filmmaker, barroom brawler, womanizer, revisionist custodian of Old West mythology. He was also a compulsive reader. Every day he dipped into a battered Bible he carried with him. Books—running the gamut from paperback cowboy novels to the latest weighty studies of existential philosophy—were always stacked beside his bedside.

And so we can be sure that Peckinpah had come across F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous quote, “There are no second acts in American life,” from his unfinished Hollywood novel, The Last Tycoon. Fitzgerald’s warning must have seemed ominous to Peckinpah, when his own first act ended abruptly in the mid-1960s, and he devoted himself to the reinvention he would need to make his masterpiece: The Wild Bunch.

In late 1964, producer Martin Ransohoff fired Sam as director of the Steve McQueen poker fantasy, The Cincinnati Kid. This followed Columbia’s barring Peckinpah from its studio lot after he fought with executives over the failed desert epic Major Dundee. His acclaimed work on TV Westerns in the 1950s and his prize-winning early film, Ride the High Country, were yesterday’s news. Just entering his 40s, Peckinpah was essentially washed up in the American movie industry. Blacklisted. Not for political reasons, but for being difficult to get along with. His first act in American life was over; would he get a second?

Peckinpah spent the next 18 months in a frustrated purgatory, filled with the sort of grit and determination and narrow misses that would make a classic comeback movie. At first, when the phone rang, the voice on the other end might offer him a writing job but no opportunities to direct. This provided money to cover the electric bill but did nothing to repair his reputation as a film director.

Peckinpah’s roots were in television, and it was the “idiot box,” as it was known to its detractors in the 1960s, that got him back into the director’s chair. He was hired to adapt and direct Katharine Anne Porter’s short novel Noon Wine. The hour-long episode of ABC Stage 67 was broadcast on November 23, 1966, to enough critical acclaim to get Peckinpah a job scripting a Pancho Villa movie. He had been given a vague promise of a directing opportunity, but that was scuttled, when star Yul Brynner saw to it that he was fired from Villa Rides. Peckinpah’s sin? Making Villa too realistic. Now he was banned from Paramount’s lot too.

By the mid 1960s, the American film industry was undergoing profound changes—major studio profits were falling as the moguls from an earlier age died or retired, and audience tastes shifted away from standard movie fare. Jack Warner, head of Warner Bros., was forced to sell his controlling interest in the studio that bore his name to a company headed by Eliot Hyman, who became studio president. Hyman chose his son, Kenneth, to be head of production.

Kenneth Hyman was only in his thirties, but he already had a commendable record of producing movies that were popular with critics and appealed to the burgeoning 1960s youth market. Hyman screened Ride the High Country and decided he wanted Peckinpah to direct for Warner Bros. Hyman dispatched producer Phil Feldman to Sam’s place in Malibu with an offer to direct a heist film with the working title of The Diamond Story.

Peckinpah didn’t trust Feldman and he thought the offer to direct was bogus: “I’ve heard that shit before.” He figured what Warner Bros. really wanted him to do was rewrites on the project. But the offer was legitimate, and soon Peckinpah was on board at the studio. He brought with him a screenplay called The Wild Bunch, a project that had been kicking around Hollywood for a few years already.

The Wild Bunch had been dreamed up by a stuntman named Roy Sickner, who saw the movie as a shoot-’em-up set in Mexico in the 1870s. Eventually Sickner hired Walon Green, who had written for TV documentaries but who had never written a screenplay, to take a shot at drafting a treatment and a script. The young Green proved up to the task. After convincing Sickner to move the setting to the Mexico/U.S. borderlands during the Mexican Revolution, Green hammered out several drafts of both treatments and screenplays. He created the basic story and most of the characters before he signed off on The Wild Bunch and returned to TV work. Peckinpah took up where Sickner left off, adding characters, and, while leaving the essentials of the storyline unchanged, overhauling dialogue, composing new scenes, and sharpening the thematic structure.

It wound up being a tightly constructed tale about a group of outlaws who have outlived their time. After a foiled attempt to rob a Texas railroad office, they flee to Mexico and hire out to rob arms from a train north of the Rio Grande, which they succeed at doing, setting themselves up financially for life. However, they give it all up and sacrifice their lives in order to do the ethical thing and attempt to rescue a comrade from torture and execution.

Nothing Peckinpah ever worked on was closer to his heart than The Wild Bunch. In most ways, he was a man out of his time himself, having been raised among old-time cowboys working ranches outside Fresno, California. His core values adhered more to the code of the West than to the wounded ethics of hip 1960s Hollywood. He abhorred how technology was gutting the human spirit in the 20th century. The Wild Bunch dealt with these themes by showing how automobiles destroyed old customs and opened the door to abuse, and by showing how automatic weapons could kill hundreds of people in just minutes.

It was this vision of violence—far outside the sanitized Hollywood norms of the day—that made the script personal to Peckinpah. Violence had haunted him since his military service in China, where, as a U.S. Marine Corps observer, he witnessed bloody combat between Maoists and Kuomintang forces in the years following World War II. He saw public beheadings, genital torture, and prisoners dragged behind automobiles.

When Peckinpah and Feldman traveled to Mexico to scout locations for The Diamond Story, they wound up stuck in a hotel during a torrential rainstorm. Peckinpah dug The Wild Bunch screenplay out of his suitcase and shoved it into Feldman’s hands. With nothing better to do, Feldman read it straight through. And loved it. He told Sam The Wild Bunch would be his next picture at Warner Bros., just as soon as The Diamond Story was finished.

As it turned out, The Diamond Story never got off the ground, in part because of the incredible buzz surrounding William Goldman’s script, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which was heading toward production at 20th Century Fox. The Wild Bunch had a similar storyline and producer Feldman decided that Warner Bros. should beat Fox to the box office, which ultimately occurred. Just like that, Peckinpah was set up to direct his ideal project, The Wild Bunch, which within months would go into production.

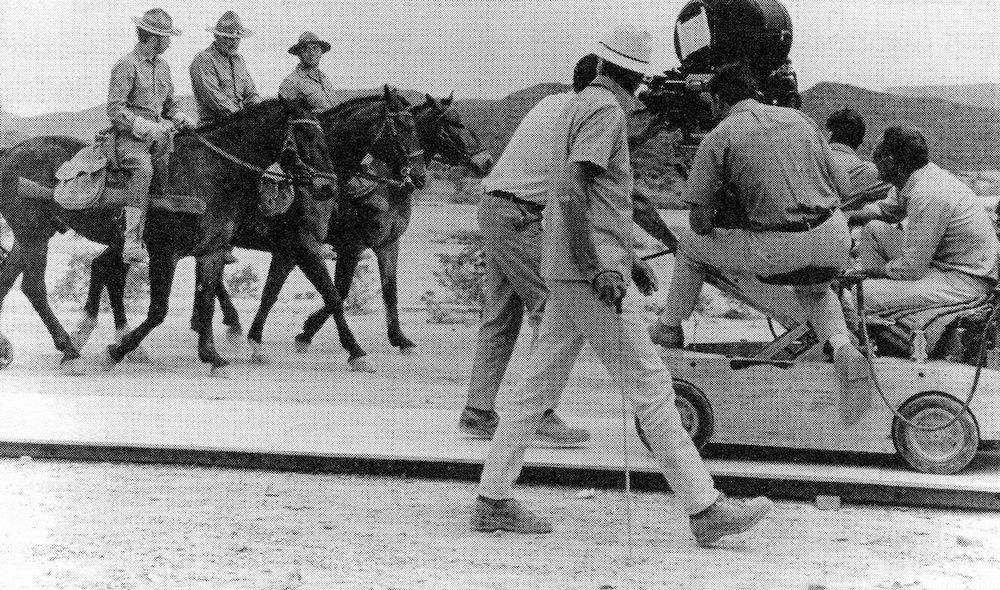

Filming the opening scene The Wild Bunch, on set in Mexico. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

He threw himself into the project, vowing not to repeat the same mistakes he made before. On Major Dundee, for example, he’d gone to Mexico to begin filming with a script that still needed much work. With the fervor of a man who knew this was his last shot at the big time, Peckinpah wrote and rewrote The Wild Bunch screenplay until it literally became a model for how script should be written. (Syd Field’s influential and bestselling book, Screenplay, was drawn from lessons he learned from Peckinpah and his work on The Wild Bunch.)

Peckinpah was also more careful selecting locations, in casting, and in choosing the crew. Many of the people he hired were from Mexico, brilliant actors and film professionals who, until The Wild Bunch, were unknown to Hollywood.

Peckinpah, once a Marine, asserted himself as commander of all studio forces on hand in Mexico for The Wild Bunch, at times to the chagrin of Feldman, a hands-on producer who was on location. Sacrificing sleep and regular meals, he often worked until midnight or after, then started again at 4:30 in the morning. Peckinpah was by the late-1960s a drunk of notoriety, but he cut his own alcohol consumption considerably, limiting himself to beer. He refused to stop working even after he developed a massive case of hemorrhoids that sometimes bled through his jeans, maintaining that he could have surgery later, after the picture wrapped.

Eliciting extraordinary performances from his actors and capturing some of the most startling images ever shot by an American filmmaker, Peckinpah knew he was accomplishing something special in Mexico. When the last interior shots were in the can, he stepped away from the set and wept. Then, working with editors Lou Lombardo and Bob Wolfe, he fashioned an extraordinary master for the movie. It had more than 3,600 edits, a record for a color film, maybe a record for any kind of film, seamlessly weaving together film sequences shot at different speeds. Peckinpah’s use of slow-motion was revolutionary.

The Wild Bunch was a controversial film in part because Peckinpah depicted violent death in a gritty, often disturbing way, and many theatergoers and lowbrow critics hated it. But from the moment it premiered in the U.S. in June 1969, more astute students of film knew he had delivered a masterpiece, one that at once opened the gates for the revisionist Westerns of the 1970s, created a whole new vocabulary for portraying onscreen violence—special effects simulating a bullet passing through a body, slow-motion death—and changed how films were edited forever. It also made a strong statement for Peckinpah as an auteur. Finally, The Wild Bunch was a financial success, one that allowed the director to make subsequent movies of significance, such as The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Straw Dogs, Junior Bonner, The Getaway, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia.

Peckinpah was an outlaw and a contrarian. He proved Fitzgerald wrong by having a second act in his American life. And it was better by far than his first.

Send A Letter To the Editors