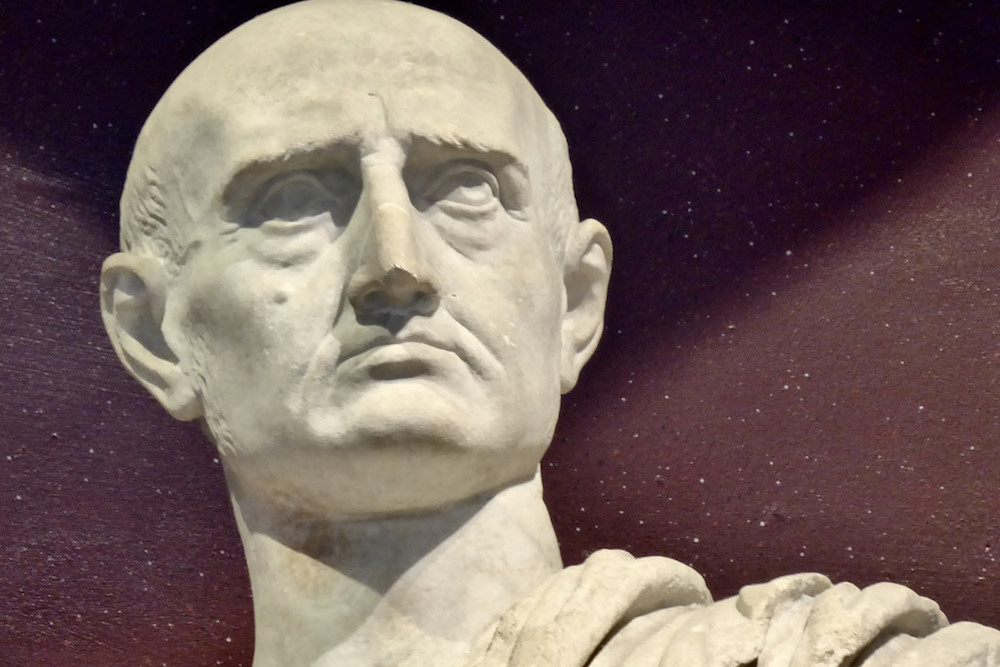

In 63 B.C., Cicero successfully pleaded for unity. But in 58 B.C., he was in exile from Rome, forced from the city by a violent populist backed by a mob. Courtesy of Flickr.

Representative democracies have wildly different life expectancies, but they tend not to live long.

Democratic governments have existed for more than 2,500 years, but most democracies have historically failed to survive more than a generation. Indeed, the strongmen whose policies are currently warping the democracies that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s in Turkey, Hungary, and the Philippines are similar to the ancient tyrants who seized control of young democratic regimes in ancient Syracuse and Cyrene.

When a representative democracy makes it through its first generation without falling into tyranny, political norms often take deep root and patterns of democratic government become quite strong. This is as true of current republics like France and the United States as it was of ancient republics like Rome. In states like these, citizens prize the voice that representative government brings and robustly defend their freedoms against the sudden and direct attacks of tyrants. Their representative democracies can last for centuries.

But even these old democracies are mortal.

As Americans living through the past 25 years know well, citizens of representative democracies are less easily roused to defend against the slow erosion of political norms. In the years since the Newt Gingrich-inspired Republican takeover of the Congress in 1994, Americans have seen government shutdowns become political tools, the confirmation of judges routinely blocked, and even the denial of a hearing for a Supreme Court justice. None of these things were normal a generation ago. Many of them were unimaginable.

And yet American voters, feeling secure that their Republic will endure such assaults on American political norms, have responded with surprising indifference to these radical actions.

This is a mistake.

The Roman Republic shows the danger that arises from this sort of complacency. Rome lived under a republic for nearly 500 years—more than twice as long as the United States has existed—and its success caused our Founding Fathers to model the nascent American Republic on its Roman predecessor.

The Romans inspired the American separation of powers, the system of checks and balances, and the presidential veto—because Rome showed how these constitutional elements compelled lawmakers to compromise with one another by preventing narrow majorities from enacting policies that did not enjoy broad support. Both Rome and the United States developed into economically sophisticated world powers because their republics gave them an unmatched ability to build broad political consensus behind difficult national decisions.

But ancient Romans eventually grew to take the survival of their Republic for granted. In the second century B.C., the tools that had encouraged compromise and fostered political consensus for more than 300 years were transformed into weapons as Roman economic expansion opened a large wealth gap between the richest Romans and everyone else.

This transformation occurred at a moment when living standards for most citizens began to plateau after two generations of rather steady growth. Romans first hoped and then demanded that the Republic respond to this widening divide between the super-rich and the struggling middle classes. In the 140s and early 130s B.C., two different politicians sponsored laws that would distribute public land to the Roman urban poor, but wealthy rivals used vetoes to block their proposed laws. These wealthy opponents of economic reform did not use the veto so that they might work out a more broadly acceptable compromise. They simply did not want to see the issue of wealth inequality addressed at all.

Finally, in 133 B.C., after nearly a decade of inaction, frustrated Romans turned to a populist named Tiberius Gracchus who was willing to use all means available to him to push economic reforms into law. Backed by angry crowds of supporters, Tiberius removed a rival lawmaker who threatened to veto his proposals and then funded his reforms by appropriating money normally controlled by his opponents in the Roman Senate. All of these things violated the political norms of the Republic, but Roman voters seemed disinclined to punish Tiberius for any of them. He was stopped only when opponents killed him in a riot.

The final century of the Roman Republic saw the Romans repeatedly look away as politicians followed the path set by Tiberius Gracchus and his rivals. Roman political life slowly but progressively degenerated into multi-year cycles of legislative gridlock that broke only when Romans voted overwhelmingly for figures who promised to do anything necessary to solve long-neglected problems. Then, when these populists inevitably overreached, their opponents often responded violently. This cycle of political dysfunction became increasingly destructive each time it reset. It ended only when Rome fell into the civil wars in the 40s and 30s B.C. that killed the Republic and enabled Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, to take power as an autocrat.

Romans failed to stop these cycles of political dysfunction in large part because they did not imagine their republic could die. Indeed, no single person or choice destroyed the Roman Republic. It was much too robust for that. But the individual Roman politicians and voters who chose not to punish political obstruction, reckless populism, and intimidation steadily eroded the Republic’s integrity.

Throughout the Republic’s final century some Romans tried to unify their fellow citizens around the defense of the political liberty they all shared. None did this more eloquently than Cicero in the aftermath of a failed insurrection in the year 63 B.C.

At the end of a speech he gave on November 8 of that year, Cicero implored Romans that “if we preserve forever this unity now established…no civil and domestic calamity can ever again reach any part of the Republic.” Relieved at avoiding civil war, nearly all Romans applauded this sentiment on that day.

The painting Battle of Actium—by the 17th-century Flemish painter Laureysa Castro—shows a decisive naval battle in the Final War of the Roman Republic. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

But the unity Cicero called upon Romans to protect lasted for only a few weeks and Romans quickly began to take stability for granted. On January 1 of 62 B.C., a political opportunist harangued Cicero in the senate. By 58 B.C. Cicero found himself an exile from Rome, forced from the city by a violent populist backed by a mob of supporters.

Cicero’s allies engaged in similarly destructive policies. His friend Cato so disliked Julius Caesar that he filibustered an entire senate meeting in which proposals that could benefit Caesar were discussed. He bribed voters to support candidates other than Caesar. By claiming a dubious religious prohibition, he even worked with his son-in-law to try to block all public business for the entire year when Caesar held Rome’s highest office.

All of these figures agreed with Cicero that Romans should come together to protect their Republic, but, taking the strength of their republic for granted, they never let republican principles dissuade them from a potent line of attack against a political opponent. This shortsightedness normalized a form of political combat in which the Republic no longer set the rules and no longer protected the losers. Robbed of its institutional defenses, the Republic could not prevent Rome’s descent into civil war or stop the emergence of a Roman autocracy. And Romans were shocked when the Republic’s impotence was finally revealed.

This is the real risk of political complacency. Until Donald Trump’s election, Americans largely turned a blind eye to the damage that the past generation of political dysfunction has done to our republic. Morally and legally dubious political tactics often seemed relatively harmless when they benefitted people and policies that one approved. But today Americans who continue to vote for the senators who block judicial nominations made by the opposing party, representatives who endorse government shutdowns, and presidents who traffic in threats and intimidation should realize that these decisions weaken our republic. We can avoid the complacency that doomed the Roman Republic. If we do not, there is a real risk that Americans will repeat Rome’s mistake.

Send A Letter To the Editors