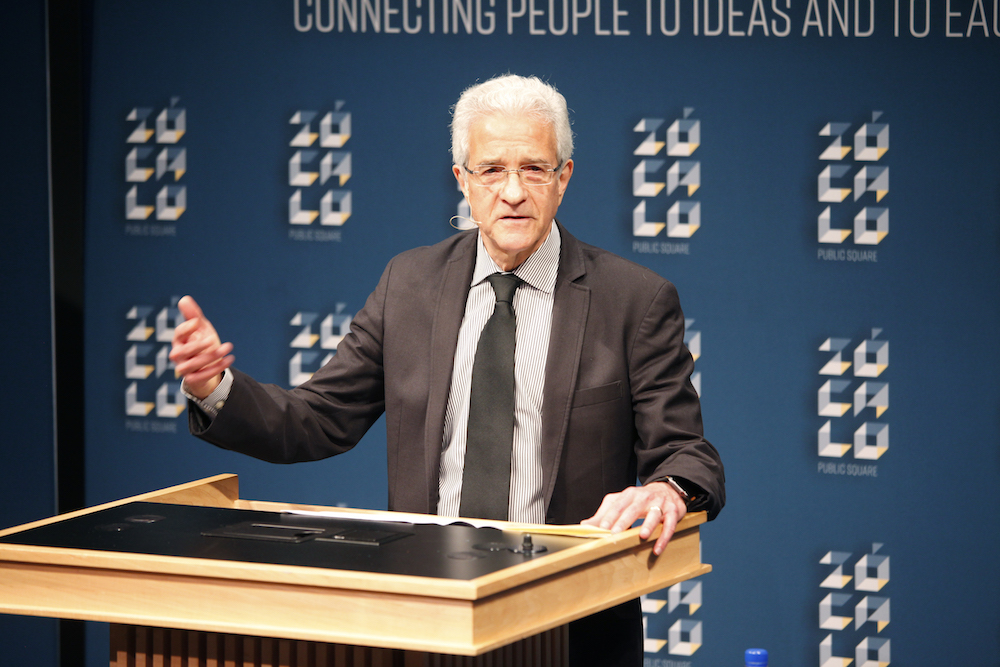

Photo by Aaron Salcido.

How can human connectedness be ripped apart? This is the question at the center of Omer Bartov’s book, Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, which earned him the Zócalo Public Square Book Prize. The prize is given annually to the author of the nonfiction book that most enhances our understanding of community and the forces that strengthen or undermine human connectedness and social cohesion.

This question was also at the heart of Bartov’s Zócalo Book Prize Lecture, “How Does Community Conflict Turn Into Genocide,” which he delivered before a full house at the National Center for the Preservation of Democracy in downtown Los Angeles. Gregory Rodriguez, Zócalo publisher and editor-in-chief, opened the evening with brief remarks and presented the Zócalo Public Square Book Prize to Bartov and the Zócalo Public Square Poetry Prize to Erica Goss. Before Bartov began his lecture, Goss read her award-winning poem, “The State of Jefferson.”

Bartov began work on Anatomy of a Genocide about 20 years ago, in the mid-1990s, after the collapse of communism and two genocides—one in Rwanda and one Bosnia, where over 1 million people were murdered. At that time, explained Bartov, “The Holocaust was seen as a case of industrial killing.” Jews were dehumanized and murdered far from the cities where they lived. “No one in this entire process was completely responsible for it,” said Bartov. There was “no direct connection” between the killers and the killed, and the victims were never seen as human beings.

By contrast, in Rwanda and Bosnia, “people were killing people they knew. These were very intimate kinds of killings,” said Bartov. Yet he also knew that only about half of Holocaust victims were killed in extermination camps. What was the relationship between the perpetrators and victims who were killed in other places and ways? Bartov decided to study one town in the borderlands of Eastern Europe, Buczacz, where his mother had grown up.

Bartov started out interviewing his mother about life in Buczacz, which her immediate family left before the Holocaust, narrowly avoiding being killed along with the rest of their extended family. Yet his mother had “fond memories of a good childhood,” he said. Buczacz “was a town of Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews, and they had lived side by side for over 400 years,” said Bartov. “And it was the relationships between these three groups and the changes in that relationship that determined the nature of how the Holocaust occurred in that place.”

Bartov traced the story of Buczacz back to the Middle Ages to find out how these groups had coexisted side by side—peacefully if not pluralistically—for centuries. “So what happened? In the second half of the 19th century, nationalism arises in this area. Nationalism takes these religious and ethnic identities and turns them one against the other.”

Violence against Jews became widespread during World War I and continued after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire, war between Ukrainians and Poles, Polish sovereignty, and the invasion of the Soviet Union. Before the Germans took control of the area in 1941, the Soviet police executed thousands of Ukrainian nationalists, who then killed thousands of Jews, accusing them of having collaborated with the Soviets.

The Germans then set out to murder the 500,000 Jews who lived in the region, explained Bartov—but they did so without a massive bureaucracy. To cover the area in and around Buczacz, they built an outpost of just 20 policemen. In the course of a year, 60,000 people were murdered, over 95 percent of the Jewish population. “They could not do this on their own,” said Bartov. They transformed Ukrainian nationalist militias into auxiliary battalions who would sweep into towns, surround them, gather the Jews, and either murder them in situ or put them on trains to camps. These round-ups were “very brutal events,” said Bartov. Neighbors are “seeing their neighbors shot on the street, under their windows.” Mass murders took place in forests, cemeteries, and synagogues.

By July 1944, what had for centuries been a multi-ethnic area had become a homogenous area made up of only Ukrainians, and “it remains like that today,” said Bartov. It’s a place with little memory of the people who once lived there and how they were murdered.

Ultimately, by studying Buczacz, Bartov came to a few key conclusions. One was that genocide on the local level was “intimate”; “the killers and their prey knew each other before the killing began.” And that killing was “extremely public.” Furthermore, the categories that had been created to help understand the Holocaust—“victims, perpetrators, bystanders”—didn’t hold. “No one was standing by. Everyone was engaged in one way or another,” said Bartov. “Most people were somewhere in the middle” You could help someone one day and profit off someone’s death the next. Most people’s behavior, said Bartov, could be categorized as falling into the “ambiguity of goodness.” Pure evil, like Gestapo members who express no remorse, is easy to understand. Goodness, by contrast, is complicated, and “most people behaved in ways that don’t fall easily into one category or another,” he said.

In the last few years, Bartov said he has begun thinking of Buczacz “as exemplary of not only the Holocaust and genocides but of the fragility of any society,” he said. “Of how we believe that we can trust the law, that we can trust law enforcement. … And then one day we pick up the phone [to call 911], and the police come and arrest us.” And when that happens, we realize that law and social order, and everything “we had built our security on has cracked, and there’s no one to turn to.” This doesn’t happen just “in a place far from here where people speak a different language,” said Bartov, “but it’s relevant to here and now.”

The question of how the lessons of Buczacz resonate today, as well as what can be done to prevent violence in the future, came up a few times in the audience question-and-answer session. Bartov noted that he was speaking as a historian, and was reluctant to make simple analogies. But he clearly sees a dangerous kind of dehumanization on the rise today that he recognizes from his work. And when asked about what we can do to stem further violence, he urged the audience to remember that laws themselves can be wrong. And when we see that legal institutions are eroding our values, “we may need to declare these laws unfair,” he said. “Our duty is to recognize and not to accept it if you feel a law is immoral.”

Send A Letter To the Editors