Chasing the Sun’s Medicinal Rays

At the Turn of the 20th Century, Southern California Became a Testing Ground for Healthy Living

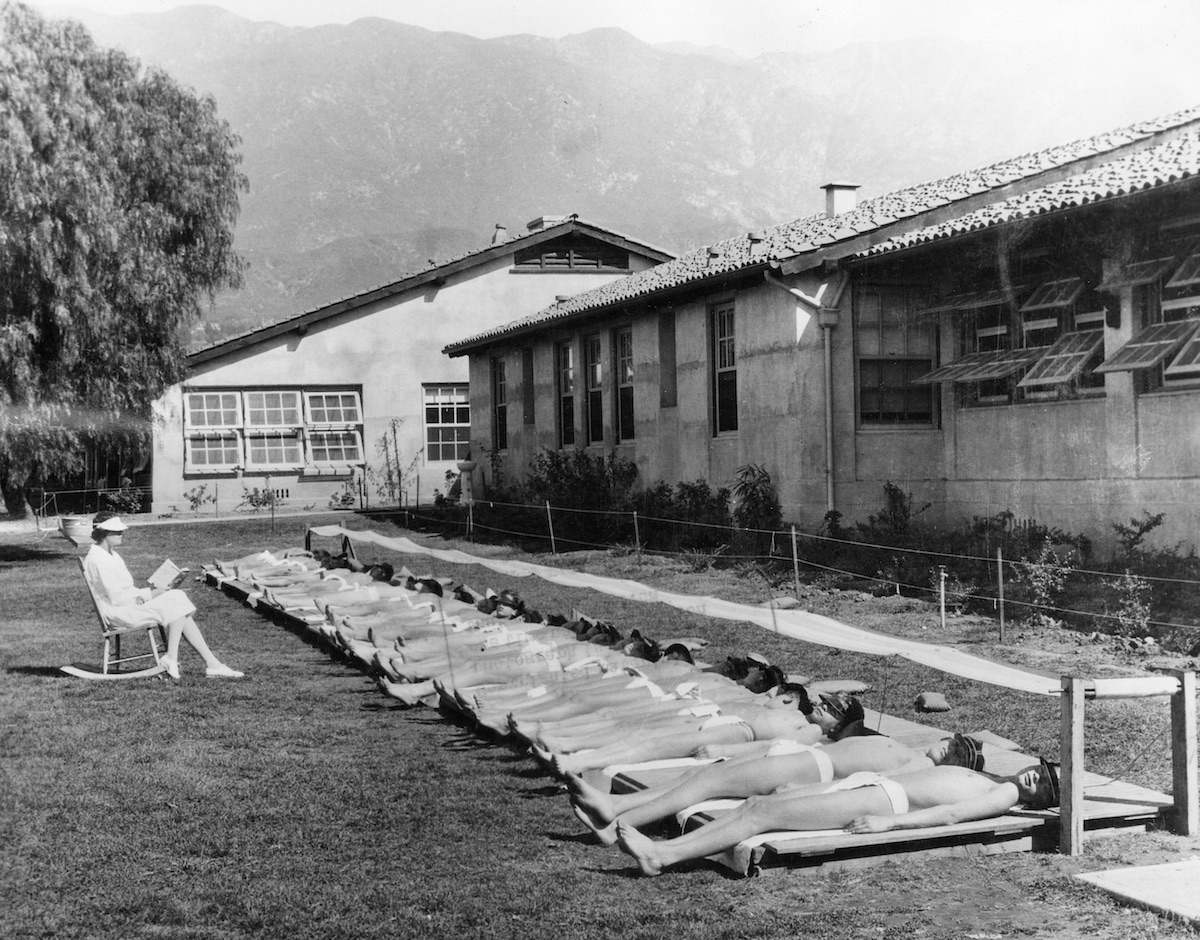

Southern California has long attracted those seeking a mild climate, a healthy lifestyle, and sunshine. According to Lyra Kilston, author of Sun Seekers: The Cure of California, the origins of the modern, healthy-living regime we associate with the Golden State has its roots in 19th-century Europe. When the Industrial Revolution had polluted many European cities and the spread of tuberculosis was rampant, open-air asylums, water and sunbathing clinics, and the like began popping up. These institutions stressed the medicinal benefits of fresh air, exercise, and the natural elements at a time when humans were looking for an escape from an urban lifestyle that was literally killing them.

Enter Southern California, with its abundant sunshine, fresh air (at least, at the time), deserts, and mountains. Seen as “a natural sanatorium,” by 1911, there were around 23 long-term health clinics in Southern California. As the sanatoriums matured, so did their design. Renowned architects of the early 20th century became involved in the crusade, including Alvar Aalto, who designed Paimio Sanatorium, a tuberculosis clinic in Finland, and a special chair known as the “Paimio scroll chair,” which “allowed patients to recline while slim back-slats provided cooling and hand grips helped in getting up.” The chair was a hit not only in clinics, but soon found its way into many of the modernist homes that became popular in California in the mid-20th century.

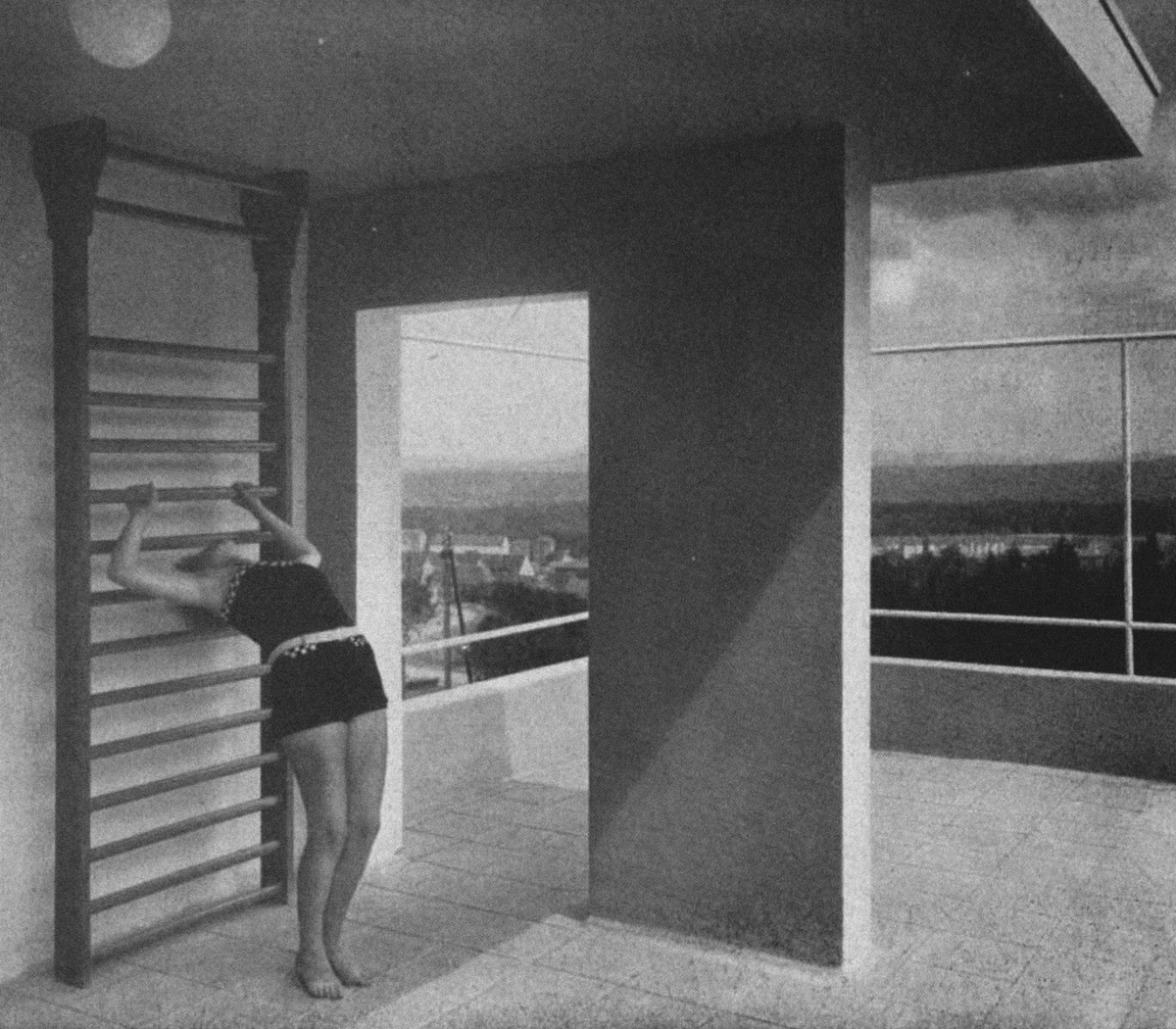

One such home was the Health House, an iconic building designed by Richard Neutra for Dr. Philip Lovell, a New York transplant-turned-naturopath who advocated for natural cures and wrote about them in a Los Angeles Times column called “Care of the Body.” The house, with its outdoor sleeping porches, abundant vegetation, and expansive windows, embodied the values Lovell championed. Neutra described the home as a “machine in the garden,” and it would come to exemplify the architectural movement known as California Modernism.

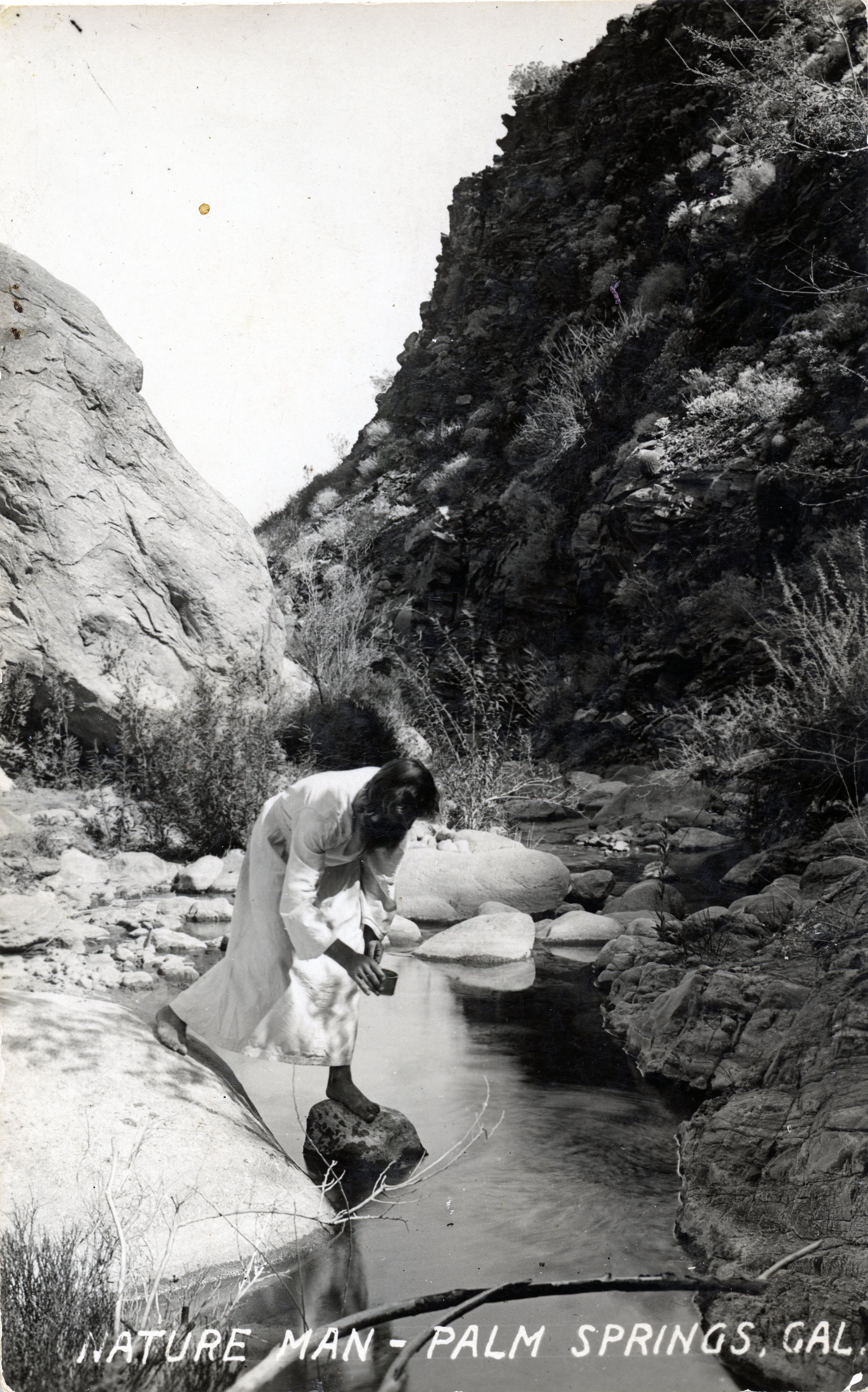

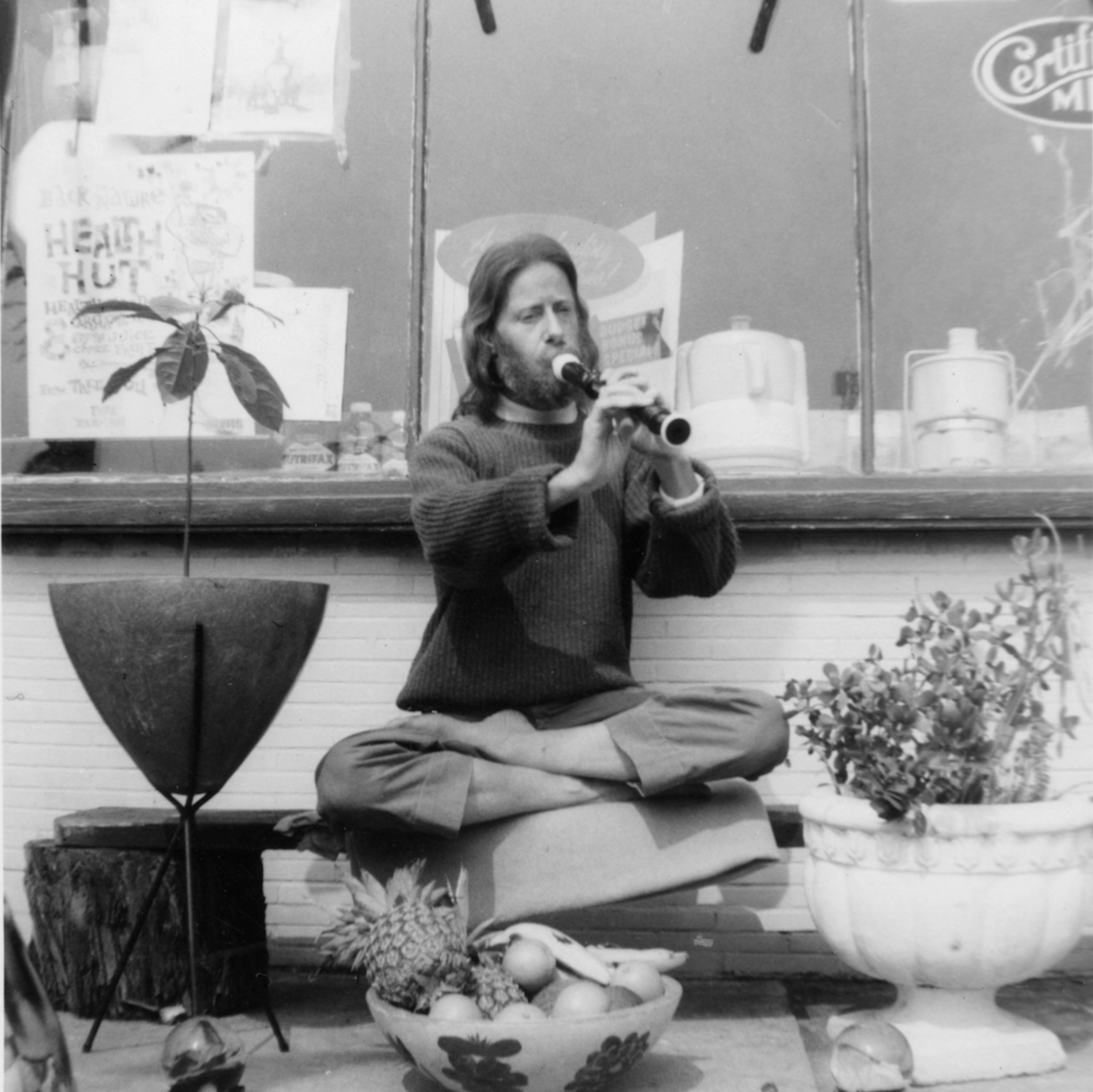

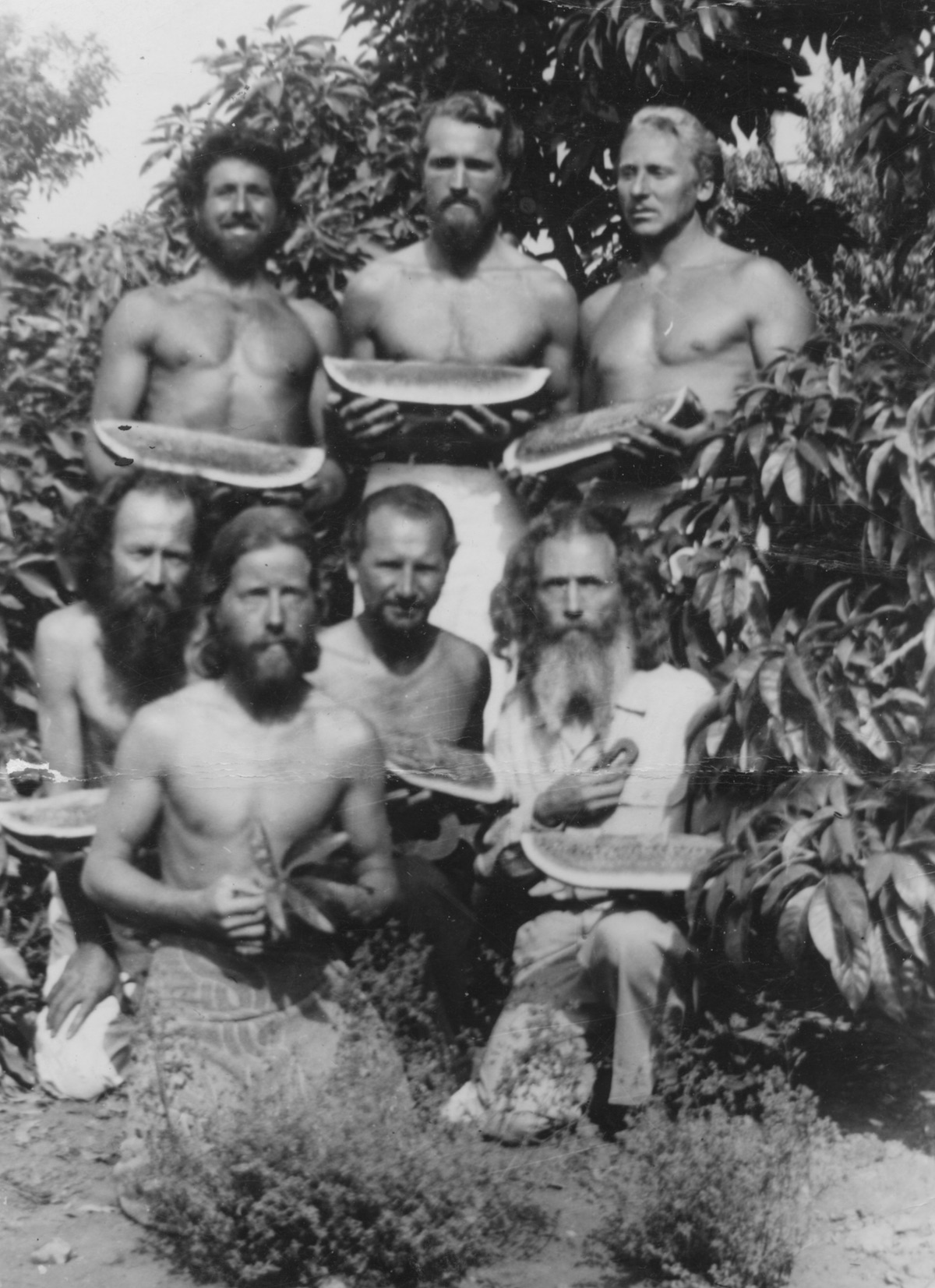

Some California sun seekers immersed themselves in nature itself. William Pester, born in Germany in the late 19th century, ventured into the California desert, making a hut from palm fronds and wood. Kilston writes that he was long-haired, richly bearded, and “wore homemade sandals and often nothing else.” Pester believed that the troubles and sicknesses of mankind came from a departure from nature, and so, this “Hermit of Palm Canyon,” as he came to be known, sought refuge from the modern world in the desert around 1906. He foraged for food, lived simply, and was one of the first “back to nature” enthusiasts in California. When tourists caught wind of Pester, his first instinct was to retreat farther away, but he soon capitalized on their curiosity and sold postcards with his image on one side and his guidelines for healthy living on the reverse. Pester and his contemporaries—a group known as the Nature Boys—were prototypes of the hippies of the 1960s.

The profound influence of these sanatoriums, health-conscious design, and the lifestyle of the likes of William Pester continue to resonate in present-day Southern California. Sun Seekers highlights these lesser-known characters and stories and traces the evolution of Southern California’s health-focused culture, recycling trend after trend—from holistic celebrity doctors to restaurants promoting “living” foods. So while the mythos of Southern California shape-shifts, the belief that the land and climate is a cure-all continues nonetheless.

Send A Letter To the Editors