Photograph of the Gangnam district in South Korea. Courtesy of Francisco Anzola/Flickr.

I grew up in the section of Seoul known as Gangnam, long before Psy’s “Gangnam Style” became a worldwide K-pop hit by touting the neighborhood, its affluence, and the rise of Korea’s pop culture. Yet the seeds of Gangnam’s eventual cultural influence were present even then, and I was there to witness the transformation.

My family lived in a modest, if not crammed, apartment unit tucked away in a far corner of the neighborhood. We moved there in 1987—the same year South Korea had its first democratic elections—and just in time to catch the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul on television in our new living room.

By 1996, Gangnam had already become known as the home base of the nouveau riche. Although I went to middle school with the kids who were among the first in the entire country to adapt the latest fashion trends otherwise only seen on TV, my life then was fairly ordinary.

Middle schools across South Korea still had gender-divided classrooms, and ours had just changed its school uniform policy to let girls wear pants instead of skirts. Still, we weren’t allowed to perm or dye our hair, or even let it grow longer than 3 centimeters below our ears. When school ended at 3 p.m., my friend and I headed to a nearby tteokbokki, “hot and spicy rice cake,” truck for the two-dollar snack.

My cooler classmates, on the other hand, headed to the school back lot to smoke cigarettes and practice dancing to the hottest new songs by the Seo Taiji and Boys, Deux, and Roo’ra—three of the first generation of South Korea dance music groups known for their intricate moves and catchy, hip-hop beats.

I was not one of these cool kids. I wasn’t allowed to cut my hair so that my bangs would rebelliously cover my eyes. My weekly allowance was just 6,000 won ($5), and I couldn’t afford to buy the most popular brands of clothing like Stüssy, Fila, or United Colors of Benetton.

What I did share with the cool kids was a longing to escape from our rectangular classroom in our rectangular school. There we were fed too much math, biology, grammar, and other things that prepared us for future national college entrance exams, and received too little of the most important information, like how to love ourselves or how sex works. Every day followed the same formula; I went to school, then to hagwon, or “cram school,” to prepare for those exams, did homework, and went to sleep, on repeat.

My classmates’ daily back lot dance practices were fueled by a pent-up anger at having to conform to this educational system that did not allow us to speak until we “made it” to college–when we’d finally become adults and mattered to the world.

At 14, I wasn’t dancing or speaking, but dance music groups—not yet K-pop but dance gayo (dance-based popular music)—spoke to me. The young dancer-singers wore the kind of things that I wasn’t allowed to wear, which thus signified liberation—baggy pants that dragged to the floor, dreadlocks, large hoop earrings, and long gold chains around their necks. They seemed to inhabit a different world from everyone I knew—an imaginary world of gangsters, hip-hop, palm trees, and Los Angeles.

They were a screen dream, to which television offered the sole portal that enabled my imagination, since my only electronic gadget at that time was a small device that connected to a blinking, blue-toned Bulletin Board Service, or BBS, with a loud screech of its modem.

1997 brought with it the monumental International Monetary Fund crisis, or Asian financial crisis. Overnight, South Korea became immersed in a maelstrom of bankruptcies, unemployment, divorces, and suicides. The IMF offered the country a bailout. More than half of all of the powerful chaebol conglomerates shut down. Some young parents left their newborn babies at orphanages. A national gold drive took place to repay the loans from the IMF; 3.5 million people nationwide collected a cumulative 226 tons of gold, according to Forbes. People donated wedding rings, trophies, and even gold tooth fillings.

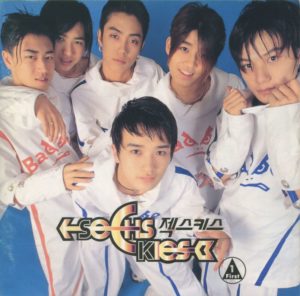

As South Korea reeled from the economic crisis, another monumental event took place: the debut of SechsKies (or in short, “Jekki”), the first-generation K-pop idol group. Their spiky moussed hair, youthful faces, slender physiques, and entertaining personas made them instant heartthrobs for us ’90s pubescents. My teenage self was swept up in their popularity. At the time, I had developed a secret crush on one of the girls in school, and was troubled about my burgeoning sexuality. When my crush fell for one of the boys in SechsKies, I followed suit—not only because I wanted to stay close to her, but also because SechsKies was the hipster currency of the entire school. You had to know all about these “idols” if you wanted to join conversations, belong to friend groups, or just be relevant in teenage life, even as the whole country seemed on verge of crisis.

As a nerd, I paid the idols respect the best way I knew how: I became a fan fiction writer. I wrote all day, every day—secretly scribbling away in my notebooks during classes, and typing them up in my little dial-up BBS machine at night. (I had to muffle the modem noise lest I woke my parents). I wrote out imaginary romantic scenarios between the SechsKies members Jae-jin and Ji-yong, which soon became a complicated love triangle as Ji-yong and Ji-won realized their feelings for each other. To pay homage to my fellow SechsKies fans, I cast members of the rival dance-idol group H.O.T. as antagonist thugs.

My unexpected 15 minutes of fame arrived in 1998—the same year that President Kim Dae-jung’s administration started investing in creative industries through the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism—when the SechsKies fan club on the Chollian BBS network began to read my ninth-grade erotica of K-pop idols making out with each other.

Since my name was not on the stories, I was not exposed as their author, but in school I became a minor celebrity. During the day, I would circulate my handwritten work throughout classes, so that my readers from the eight different homerooms in our class—including my crush herself—could request particular romantic scenarios in the next episode. In the privacy of my little room at night, I typed up the fan fiction magnum opus I had scribbled in my notebook throughout the day, and distributed it online. I returned to the real world only to flip over my SechsKies cassette tapes (all four albums) from side A to side B, then from side B to side A.

My parents, who were part of the so-called 386 generation (named after the newest PC in the 1980s, when they came of age) did not understand my interest in the SechsKies. My father was born two months after the end of the Korean War. His parents’ generation experienced postwar poverty and division, and had sacrificed democracy for economic development. By the 1970s, my mother was among the student demonstrators to protest Park Chung-hee’s military regime.

But neither of my parents could understand my rebellion against the educational system. Nor did they appreciate why I was glued to the TV to watch SechsKies perform live during weekend prime time TV, via the big three music shows aired on public TV channels KBS Music Bank, SBS Inkigayo, and MBC Music Camp. They dismissed my pubescent frustrations as symptomatic of the new brat culture.

K-pop quickly became a marker in adult minds that the entitled Generation X kids like myself could care less about democracy and nationalism.

While endless nights of fan fiction sustained me through middle school, South Korea went through the IMF-mandated socioeconomic restructuring, and paid back its $58 billion debt nearly three years ahead of schedule, in August 2001. The next year, South Korea successfully co-hosted the World Cup with Japan. Through this recovery, the costs of living soared in Gangnam, and my family moved out of my childhood home in 2004.

Walking down the familiar road towards school one last time, I remember noticing a flock of what seemed like mummies in broad daylight, with their faces bundled up in compression bandages, bold, black marks circling around their eyes like a kid’s imitation of a panda bear, and traces of pain behind their eyes. Armed with shopping bags, these apparent mummies crowded the doorways to every store, and even lined up at my favorite after-school tteokbokki truck.

Later on, I learned that I had encountered Gangnam’s transformation into a mecca of medical tourism. Alluring images of K-pop idols and before and after plastic surgery ads soon flooded the streets. This was no coincidence: There was a calculated effort by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism to turn both K-pop and cosmetic surgery into export-oriented industries in the new millennium. Everything seemed so fast and glitzy in the streets of Gangnam, as if the IMF crisis had never happened.

As the scholar Marcus Tan has argued, Psy’s global megahit “Gangnam Style” embodies the merger of local, global, spatial, and temporal dimensions through the speed of sound and the internet. Tan also alleged that the song represents the French cultural theorist Paul Virilio’s concept of the dromosphere, or “a world asphyxiated by speed and arrested by a dictatorship of movement.” This is a pretty apt description of Korea’s transition from the end of the 1990s to the 2000s.

K-pop still moves at this speed. Countless girl and boy groups debut every year, and most of them fail to survive the industry that feeds on the speed of sound, youth, and newness. My 14-year-old self listened to Seo Taiji and Boys, Deux, or Roo’ra on my Aiwa cassette player, but today you can hear any K-pop song on almost any medium, anywhere in the world. Fan fictions, too, now have globalized platforms like Wattpad, which is simply incomparable to its BBS precursor in scope and size.

A couple of weeks ago, a student in my K-pop seminar at Columbia University told me that she’s been losing sleep reading BTS fan fiction throughout the night. “It’s a rabbit hole,” she said with glee and grimace. “Sometimes the internet K-pop fan community seems like an ideal alternate universe I’d rather live in, but sometimes it feels like a pointless, psychedelic escape that doesn’t solve any of my real problems.”

I smiled, nodded, and agreed.

Send A Letter To the Editors