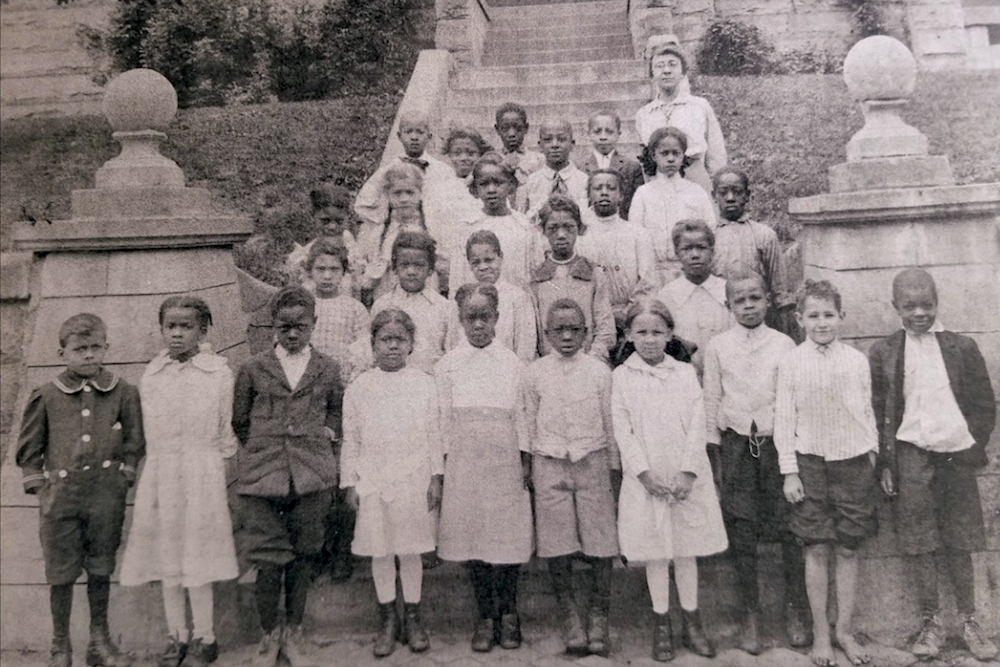

Photograph of Sumner School students, 1900. Courtesy of Michael Rice.

During the Civil War, in a town called Parkersburg on the western edge of the newly declared state of West Virginia, a group of black men gathered one evening in a barbershop. As Robert Simmons, the owner, finished cutting the last man’s hair, the group discussed starting a school.

Simmons and a man named Robert Thomas led the conversation, which became somewhat contentious. All of the men in attendance agreed that their children ought to receive a formal education similar to that given to the wealthy white boys and girls across town. Their only disagreement was over how to provide proper instruction to black children when it was against the law to do so.

Some months later, seven of these men formed the Colored School Board of Parkersburg. In December 1862, the men, who came to be known as the “Sumner Seven,” would manage to open one of the earliest and longest-lived schools for black children south of the Mason-Dixon Line. The story has largely been forgotten, but the fight to establish the school deserves a place in American history. It shows the extent to which, even in slave states, black Americans worked to secure a future for their children.

When the group of would-be school founders first began meeting, several counties had already seceded from the state of Virginia in order to stay with the Union. But the state of West Virginia had not been formally recognized. With the war underway, the men understood that if the Union lost, Parkersburg might very well remain part of a slave state.

The potential threat to their freedom loomed large, making it no surprise that they feared leaks of their plan. A loose network of underground instruction had developed in some regions, but education of black Americans in the South remained largely a clandestine activity. Under an 1819 Virginia state law, anyone convicted of teaching reading or writing to “slaves, or free negroes or mulattoes mixing and associating with such slaves at any meeting-house or houses” at any school could be punished with up to 20 lashes from a bullwhip. Extralegal punishments might be worse.

The Sumner Seven met in secret at the home of Robert Thomas, adopting bylaws and a constitution for a school that would be financed, opened, and operated by and for African-Americans. Despite threats from whites, they had a school up and running in less than a year.

The Colored School of Parkersburg’s first schoolmaster was Rev. S. E. Colburn. Sarah Trotter and Pocahontas Simmons served as the primary teachers. Principal Colburn was paid $25 per month for his services and was employed for four years. Initially, the school asked families to contribute $1 a month per child to help fund the expenses of the school and pay its teachers. Families who could not afford the tuition often bartered for their child’s school expenses by providing goods or services.

What the Sumner Seven proposed was a novelty in more than one way. Before this school for black youth opened in Parkersburg, no public schools existed for any area children, black or white. Starting in 1848, some wealthy white boys had begun taking private lessons from a local professor, John Nash, while wealthy white girls would soon attend the DeSales Heights Visitation Academy, beginning in 1864.

The school’s first instructors went door to door to recruit children, and classes were held at a variety of locations during the early years. The curriculum included reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and English grammar. Early enrollment records indicate that in 1865 the school had as many as 47 pupils—25 boys and 22 girls.

The Sumner Seven managed to keep instruction going until public funding became available for educating all area children. After years of reluctance among the general population to collect taxes for public education, Wood County set up a public school system for white children in 1866. The same year, the board voted to incorporate the school for African-American children into the city’s public school system, making education free for all students.

Yet it would take much longer for the school to receive the resources needed to instruct its students. Children often had to make do with secondhand materials from white schools. They would not move into a two-room schoolhouse until 1874, and finally had a custom-built schoolhouse at a permanent location in 1886. In time, the school adopted a new name—Sumner High School—in honor of Massachusetts congressman and abolitionist Charles Sumner.

The high school held its first graduation ceremony in 1877, and its last class graduated in 1955. Facing pressures to begin working, many children who attended the school could not continue their studies long enough to get a high school diploma. Nevertheless, approximately 400 children graduated from Sumner High School. This pioneering institution, the first black school in the state set up with no outside assistance, served as a blueprint for similar schools in Clarksburg, Martinsburg, and Charleston. When desegregation began in the 1950s, students were academically prepared to assimilate into the public school curriculum.

Sumner had elaborate graduations and creative programming for commencement. The school hosted celebrities, including educator Booker T. Washington, Olympic sprinter Jesse Owens, historian Carter G. Woodson, and composer W.C. Handy. Sumner High School was also recognized for the number of its students who pursued higher education or became leaders in the community. Sumner alumni included dentists, physicians, lawyers, and successful entrepreneurs. In some subjects, they may have gotten a more complete education than their white peers, learning about key moments in African-American history as part of their U.S. history lessons.

As a Parkersburg native, I remember friends and family members discussing with great fondness the education they received at Sumner. My uncle James played on four state basketball championship teams while attending the school. My mother, grandmother, uncles, and godfather all attended Sumner. I went on to get my doctorate in education, something I credit to the lessons and inspiration provided by my family. Their stories were the impetus for my curiosity about the origins of the school and personal quest to keep the story of Sumner High School part of our state and national history discussions.

I no longer live in town but have often sat in my car staring up at the last remaining part of the now empty and rundown Sumner building. I wonder what it was like for those students who grew up in a different world, one in which many freedoms were nonexistent. I am profoundly grateful for the courage shown by the Sumner Seven and the school’s first students, who embraced learning for black children before the Emancipation Proclamation had even been issued.

Though Robert Simmons began as a barber, he later became active in politics and was offered an ambassadorship to Haiti by Ulysses S. Grant, which he declined for unknown reasons. If it weren’t for those early discussions in his barbershop and the forethought and courage of Simmons and his collaborators, the school’s first graduation would never have taken place. It might have been years or even decades before education became an option for nonwhites in a small town on the Ohio River. The members of the Sumner Seven—Robert Thomas, Lafayette Wilson, William Sargent, Robert W. Simmons, Charles Hicks, William Smith, and Matthew Thomas—are names we should remember.

Send A Letter To the Editors