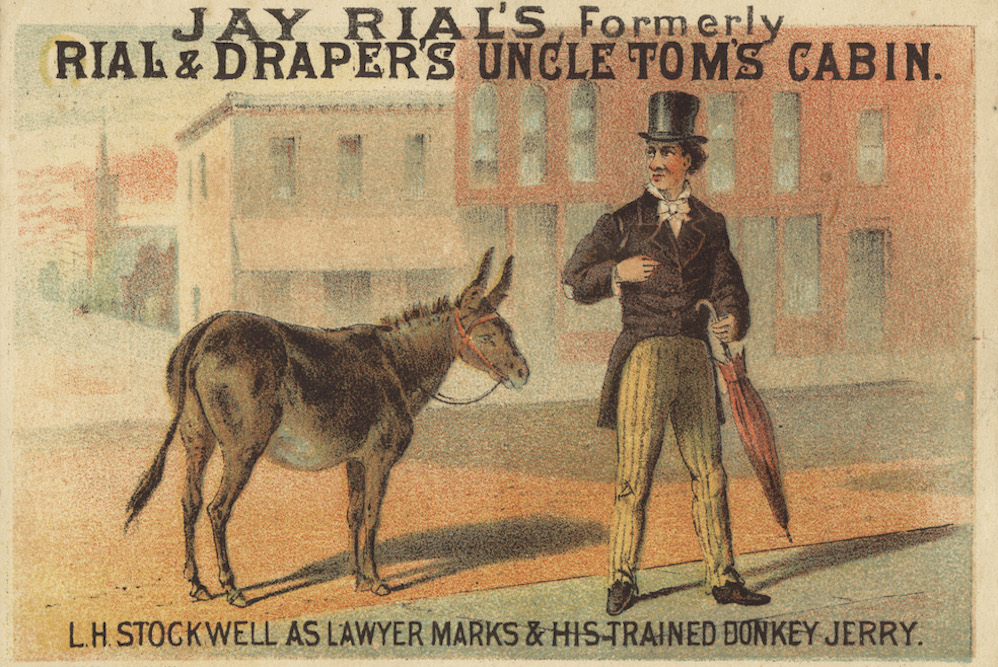

Literary characters like Lawyer Marks, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, seemed to be exempt from conventional ethics—but nonetheless became sources of a sort of pride, promoting the idea that a true American didn’t need to be a well-formed individual to make great things happen. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Grab a burger at the James Dean diner in Prague, pay homage to the Miles Davis monument in Kielce, Poland, or stop by the Elvis fan club of Malaysia, and you’ll see how a certain brand of 1950s “cool” still shapes perceptions of America abroad. What people mean by cool can be hard to pin down, but cultural historians tend to agree on some basics: defiance, self-control, individualism, and creativity—ideals epitomized by the jazz and beat movements of the early 20th century.

Grab a burger at the James Dean diner in Prague, pay homage to the Miles Davis monument in Kielce, Poland, or stop by the Elvis fan club of Malaysia, and you’ll see how a certain brand of 1950s “cool” still shapes perceptions of America abroad. What people mean by cool can be hard to pin down, but cultural historians tend to agree on some basics: defiance, self-control, individualism, and creativity—ideals epitomized by the jazz and beat movements of the early 20th century.

Long before these characteristics were cool, however, the term was linked with American identities in a very different way, and in very different contexts. Tracing its history helps us understand how we have come to embrace a certain kind of contradictory character as a national hero.

If you were a regular theatergoer in the 19th century, you’d have been familiar with a character called the “cool Yankee”—though he looked almost nothing like what cool would come to be. Amoral, selfish, and bumbling, he was a stock character who nevertheless always managed to save the day.

Although this figure was more prevalent on stage than in print, Hank Morgan, the fast-talking engineer in Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, is a great literary example: a cruel con man who readers are nevertheless expected to like. The cool Yankee is worth remembering, because the popular imagery of Americanness has never entirely managed to move past the weird faith it represents: the belief that our worst qualities might lead us in positive directions.

To grasp the true 19th-century meaning of cool, it helps to understand the meaning of another slang term of the time, “’cute.” In the popular parlance of the 1840s and ’50s, “’cute Yankees” (just as in ‘Merica, the apostrophe signals a missing “A”) were comic figures, who stood out for their ridiculous attempts at being acute, or clever.

Newspaper readers were very familiar with the ‘cute Yankee’s failings. In one 1846 article from a Connecticut paper, for instance, a man refuses to hand over his ticket to a boat operator, thinking that the worker is trying to steal it. “The old fellow being a regular and ‘cute Yankee, was not easily gulled,” the story concludes. An 1859 New York Times article recounted a “female ‘cute Yankee” who, called into court for selling bootleg whiskey, brought a borrowed baby to appeal to the judge’s sympathy. ‘Cute was anything but admirable: it stood for underhandedness, amorality, and, often, plain stupidity.

Despite the negative qualities of ‘cuteness, though, ‘cute Yankees were figures of pride—folk antiheroes of early America. As one article telling the story of a “‘cute Yankee quack” selling fraudulent medicine in England put it, for instance, “such assurance is almost sublime.” But at least one journalist, writing for The Knickerbocker in the 1840s, was led to question why, in the “land of steady habits,” Americans were so fond of celebrating hacks and swindlers. What, the article asked, is the “morality of ‘cuteness”?

Nowhere was this question more glaring than in the 19th-century theater’s treatment of slavery. Although Harriet Beecher Stowe didn’t mention ‘cuteness in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, playwrights who adapted the blockbuster novel for the stage almost invariably added a ‘cute Yankee character to the story. The three most famous of these—George Aiken’s “Gumption Cute” and “Lawyer Marks”, and Henry J. Conway’s “Penetrate Partyside”—are significantly different, but share key similarities. First, they are pathetic: Cute is a failed teacher, spiritualist, and plantation overseer; Partyside is a drunk who has lost his savings to bad investments; and Marks—whose hallmark is riding a sad-looking donkey—is simply sleazy. Second, they provide stark contrasts to Stowe’s strong antislavery stance: Cute is happy as an overseer, Partyside is more interested in booze than liberation, and Marks is a slave trader. Third—and here they resonate with other ‘cute Yankee antiheroes—they each have a prominent role in the play’s depiction of final justice. Some versions of Aiken’s play include a tableau in which Cute stands triumphantly over the evil slave driver Simon Legree, whom he has knocked out by accident; in others, Marks shoots and kills Legree; Partyside speaks the final words in Conway’s version, wishing Uncle Tom’s descendants happiness.

When historians have looked at these characters, they have described them as images of compromise, helping dramas appeal across sectional lines by tempering Stowe’s moral message, soothing Southern spectators who might feel targeted by the story. But when we see how these Yankee figures bridged a transition between ’cute and cool—a shift that put a new spin on what exempted them from traditional moral standards—it becomes clear that they also came to represent a special form of American exceptionalism.

By the turn of the 20th century, these characters were no longer being called ’cute. Gumption Cute, despite his name, came to be known as a “cool Yankee.” Another example is Salem Scudder, the overseer who accidentally saves the day in Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon, a hugely popular play about an enslaved, multiracial character, when his camera malfunctions. Scudder is nowhere called cool in the 1850s play, but soon critics were referring to him that way. As noted by one New York Times review, later reprinted in Charles Pascoe’s The Dramatic List, “the cool Yankee, Salem Scudder … appears to perfection” in The Octoroon. The change in vocabulary entailed a subtle shift in emphasis. Where ‘cute stressed calculation and cunning, or lack thereof, cool emphasized exemption from the rules.

This shift in the language of the theater was paralleled in lighthearted newspaper coverage of “Yankee” stories. Cool had long described the state of keeping one’s head in a tense situation, but increasingly over the course of the 19th century it came to mean holding on to one’s freedom in the face of oppressive authority. One article describes a “cool servant,” for example, who responds to a request for breakfast by saying no thanks, “I ain’t very hungry this morning.’” Another tells the story of a couple who elope in a “cool way” by inadvertently holding the ceremony in view of their parents. The bumbling and misunderstanding of the ‘cute Yankee is still here, but stories like this make it less about what you can potentially steal from others, and more about skirting rules that might otherwise hold sway.

Americans embraced the idea of coolness because it smoothed over many of the contradictions fundamental to their national culture. Imagining a core of goodness and positive impact under surfaces of vice and stupidity helped Americans channel the optimism that went along with being a new nation, even as they continued to observe clear failures of justice throughout the Gilded Age and the end of Reconstruction. Cool helped them turn cultural insecurity into a form of pride.

As articles like The Knickerbocker piece on the “morality of ‘cuteness” suggest, these Yankee figures had always seemed to be somehow exempt from conventional ethics—even to the chagrin of some American critics. But the emerging vocabulary of coolness brought this trait even further into the foreground. Before icons like Lester Young and Marlon Brando made American cool into a badge of stoic, poised individualism, in other words, characters like Lawyer Marks and Salem Scudder promoted the idea that a true American didn’t need to be a well-formed individual to make great things happen—the ultimate American exception.

Unaccountability will never have its own diner, or a monument in its name. But the idea that being American meant a special license to be callous, uninformed, and clumsy and still make a positive contribution to society has never entirely gone away. Wherever these traits become points of pride, we are in the presence of the original American cool.

Send A Letter To the Editors