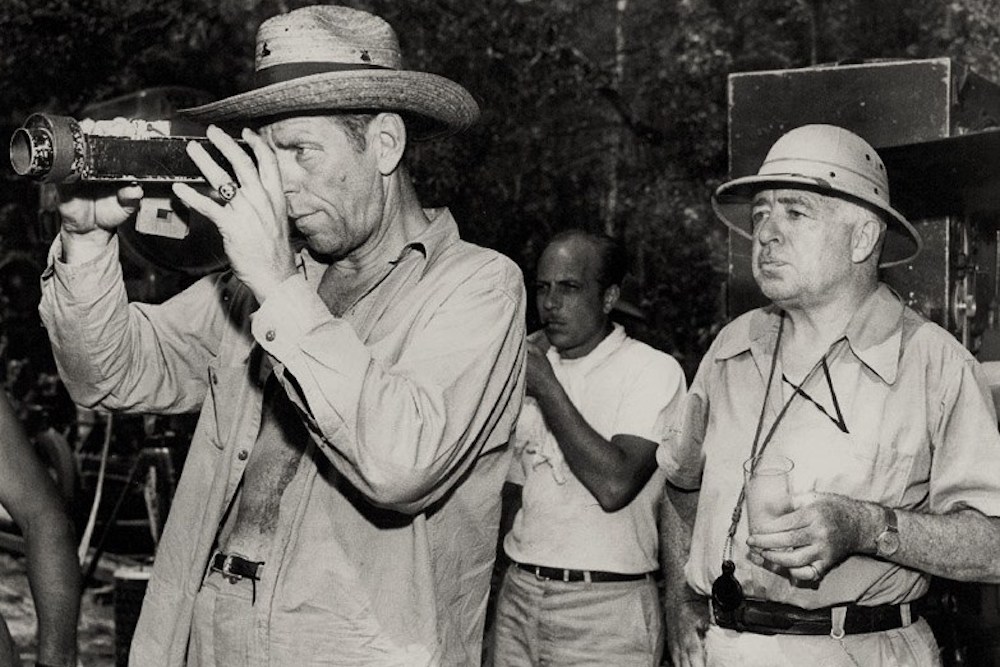

Cinematographer Leonard Smith and director Clarence Brown on the set of The Yearling in 1945. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Clarence Brown was a major figure in Hollywood’s Golden Age, directing Garbo and other glittering stars in films spread over five decades. He boasts the dubious—or is it admirable?—distinction of being nominated the most times for a best director Oscar without ever winning one. So how did he fade from public consciousness?

The explanation may lie, perversely, in the sheer length of Brown’s career, as well as the particular politics of the studio where he made his home for almost 30 years. MGM boasted that it had “more stars than there are in the heavens themselves,” but the prestigious Lion believed more in the power of producers than directors. The story of Brown’s career also suggests that he knew his country too well, and that there were great risks to demanding too much empathy from American audiences.

Brown arrived on the MGM lot in 1926, with 10 years’ experience under his belt—first as an apprentice to the great French director Maurice Tourneur, later as a director at Universal and United Artists. He was skilled at managing the foibles of his performers, a talent he picked up in his early career as a juvenile performer in local and regional theatre in Tennessee.

At MGM, he quickly learned that he was there to serve the system, when he was assigned a potboiler, Flesh and the Devil, and a most reluctant cast, led by John Gilbert—a bona fide star who felt the material was unworthy of his talents. The cast also included a Swedish import, Greta Garbo, who was then still floundering in the strange world of U.S. movie productions. It may not have been the most auspicious of starts, but Brown came to realize that he had extraordinary assets at his disposal. Aided by cinematographer William Daniels, he won Garbo over, earning her trust and capitalizing on the very real chemistry between her and Gilbert.

Brown’s double degrees in mechanical and electrical engineering (from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Class of 1910) were rare, though not unknown, among Hollywood artists. (His contemporary, Allan Dwan, had a similar background). Brown’s education was certainly called into service as he worked with Daniels to achieve innovative shots, including a memorable one in which duelists become abstract silhouettes, set against an expressionist background. There’s also a montage sequence that shows Gilbert’s Leo traversing land and sea, lured by the siren call of Garbo’s Felicitas.

Brown’s problem-solving skills, so much a part of his engineering training, came to the fore as he shot one scene that depicted the lovers making a furtive retreat to a lush garden and striking a match to light a shared cigarette. To convey the atmosphere of intense intimacy, Brown and Daniels needed much of the background to stay in darkness, with only the lovers’ faces illuminated in the flare of the match: the simple yet ingenious solution they came up was to place a small lightbulb in Gilbert’s hand. Brown’s no-nonsense approach to practical problems, combined with his deep appreciation for his performers and for the medium-as-art, helped him transform mediocre material into one of the silent era’s most sumptuous odes to erotic love.

It also catapulted Brown into the echelons of A-list directors. A year later he was reunited with Garbo, suddenly the studio’s hottest star, for the risqué A Woman of Affairs, and over the course of the next decade the duo worked on five more films. When movie sound arrived and it came time to introduce the husky Garbo voice to the world, Brown was behind the camera for 1930’s Anna Christie (“Gimme a whiskey, ginger ale on the side. And don’t be stingy, baby!”).

Brown may have been too successful with the Swede, because if he is remembered at all, it’s as “Garbo’s Favorite Director.” It was a significant partnership but not an exclusive one. He worked just as often with Joan Crawford—and arguably was a better director of her than of Garbo—and even more with Clark Gable. In fact, over the course of his prolific career, Brown worked with just about every major star on the lot, from Marie Dressler, Jean Harlow and Myrna Loy to Spencer Tracy, Gregory Peck, and the Barrymore brothers.

While Brown earned the reputation of being a stolid company man, he was also a creative artist. His films often contain subversive moments and consistently display a deep empathy with figures that stand outside of, or are marginalized by, a dominant society.

In a trio of “women’s films” he made for Universal in the early 1920s—Butterfly (1924), Smouldering Fires (1925), and The Goose Woman (1925)—he coaxed subtle, complex performances from Ruth Clifford, Pauline Frederick and Louise Dresser in dramas that shed light on American culture’s obsessions with youth and beauty and the country’s profound ambivalence toward female empowerment.

His early films—such as The Signal Tower (1924), in which a young boy (Frankie Darro) becomes the pawn in the adult world of power plays and sexual tensions—also show off Brown’s great gift for conveying young people’s encounters with the adult world of regulations and restrictions. Brown became known for discovering child actors such as Claude Jarman Jr.—plucked from a Nashville school room and launched to stardom and Oscar success in The Yearling (1946)—and Jackie “Butch” Jenkins, whom Brown selected to play Mickey Rooney’s kid brother in his adaptation of William Saroyan’s ode to wartime America, The Human Comedy (1943). It was an inspired piece of casting: Jenkins’ presence brought a timeless, sincere quality to a film that too often tipped into cloying sentimentality.

Jenkins’ second film with Brown, the much-loved National Velvet (1944), shows the range of his vision with child actors. Critic Manny Farber shrewdly observed that the boy “still seems cut off from this civilization and has been wisely left.” Playing Donald, the charming-yet-wild sibling of Elizabeth Taylor’s Velvet, Jenkins is the incarnation of the child who has not yet been contained by societal strictures, not yet observant of the niceties of acceptable behavior. He’s not a major character but Brown treats him as if he were and seems to relish those moments when he can introduce Donald as a disruptive force.

The angelic, freckled face of the golden-haired Jenkins is the perfect disguise for the monstrous little Donald, the boy that collects insects in a jar and delights in exercising a ruthless power over their destinies. This is the little brother that, when faced with a sister who is suffering a bout of nervous hysteria, observes and then mimics her, in almost clinical fashion. Brown later acknowledged that Jenkins was a force of nature, so young that he understood acting only as a variation of play, but the fact that the director chose to develop his character—which had been given scant consideration in Enid Bagnold’s source novel—and retain such peculiar moments, demonstrates his skill and imagination.

It is in Brown’s late masterwork, an adaptation of William Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust (1949), that we see his full vision and potential. The central adult character, a successful black man named Lucas Beauchamp (played by the charismatic Juano Hernandez), remarks that he needs the help of teenager Chick (Jarman) to prove that he is not responsible for the murder of a white man. For Lucas, only Chick can help because he is “uncluttered,” and has yet to succumb to the accepted narratives of the adult world. The words are Faulkner’s, but the sentiments could just as easily be Brown’s: he is drawn to characters that see and feel with clarity, even if they may ultimately be contained by society.

Intruder in the Dust was not Brown’s last film, but there’s no doubt it was his most important one. In some sense, it closed a circle that had started, not when he arrived in Hollywood in 1920, but when he and his family made the move from Massachusetts to Knoxville, Tennessee, as Brown was entering his teens.

Brown’s paternal line was rooted in the South (notably, Georgia), and it was while on a visit to his Atlanta-based grandparents that he got caught up in the race riots of September 22, 1906. Brown was not the target—his white skin was protection enough—but he was psychologically scarred nonetheless, haunted by guilt that he had stood in shocked horror as black citizens were hunted down by a white mob. His guilt deepened with the passage of time, and eventually prompted him to find some way to make amends.

So he purchased the rights to Faulkner’s novel and persuaded Louis B. Mayer to let him film it on location in Oxford, Mississippi. He won over the locals by casting them in small roles, reassuring them that his film would offer a “true” portrait of their way of life, and using nearby accommodations for cast and crew (which was not so easy when it came to housing Hernandez—the main hotel in the town was hospitable only to whites).

In October 1949 he unveiled the results: a powerful, subversive, and impressively complex portrait of race relations and white attitudes toward black people in mid-century America. It boldly placed a charismatic, authoritative black man at the center of its narrative (and at the center of every shot in which Hernandez appeared), exposing the ignorance and brutality at the core of racial hatred. Unusually for a film of the time, every white character in the film is held to account, from the “trash” who seek to lynch Lucas, to the “respectable” folk who close their minds to obvious truths.

Though it was critically acclaimed by both the white and black press, Intruder in the Dust flopped at the box office and left Brown bitterly disappointed. Such a reception for a groundbreaking film is another reason why the director is underestimated, and why his work deserves reconsideration now.

His career petered out in 1953 and thereafter he settled into a long retirement. When he died in 1987, obituaries remembered him foremost as “Garbo’s Favorite Director.” But their partnership was just one chapter in an epic American filmmaking career that yielded evocative pictures of rural and small-town lives; compassionate portraits of spirited women; and timeless tales of children and adolescents navigating the wonders of this world.

Send A Letter To the Editors