Students in Chiran, Japan wave to kamikaze pilots during World War II. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Amphetamines, the quintessential drug of the modern industrial age, arrived relatively late in the history of mind-altering substances—commercialized just in time for mass consumption during World War II. In fact, the introduction of what is now Japan’s most popular illegal drug began as a result of the state promoting its use during the war.

With the possible exception of opium during the Opium Wars, no drug has ever received a bigger stimulus from armed conflict. “World War II probably gave the greatest impetus to date to legal, medically-authorized as well as illicit black market abuse of these pills on a worldwide scale,” wrote Lester Grinspoon and Peter Hedblom in their classic 1975 study, The Speed Culture. Whether in the air or in the trenches, the war enabled the rapid proliferation of a synthetic stimulant that was particularly well-suited to sleepless work and intense concentration.

Amphetamines—often called “pep pills,” “go pills,” “uppers,” or “speed”—are a group of synthetic drugs that stimulate the central nervous system, reducing fatigue and appetite and increasing wakefulness and imparting a sense of well-being. Methamphetamine is a particularly potent and addictive form of the drug, best known today as “crystal meth.” All amphetamines are now banned or tightly regulated around the globe.

While produced entirely in the laboratory, amphetamines owe their existence to the search for an artificial substitute for the ma huang plant, better known in the West as ephedra. This relatively scarce desert shrub has been used as an herbal remedy in China for more than 5,000 years and is often ingested to treat common ailments such as coughs and colds and to promote concentration and alertness—including historically by night guards patrolling the Great Wall of China.

In 1887, Japanese chemist Nagayoshi Nagai successfully extracted the plant’s active ingredient, ephedrine, which closely resembled adrenaline; and in 1919, another Japanese scientist, A. Ogata, developed a synthetic substitute for ephedrine. But it was not until amphetamine was synthesized in 1927 at a UCLA laboratory by the young British chemist Gordon Alles that a formula was available for commercial medical use.

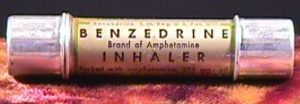

The Benzedrine inhaler hit the market in 1932 as an over-the-counter remedy for asthma and congestion. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Alles sold it to the Philadelphia pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline & French, which brought it to market as the Benzedrine inhaler in 1932 (an over-the-counter product to treat asthma and congestion), before introducing it in tablet form a few years later. “Bennies” were widely promoted as a wonder drug for all sorts of ailments, from fighting depression to obesity, with little apparent concern for or awareness of their addictive potential, and of the risks of longer-term physical and psychological damage. And thus, the stage was set for large-scale pill pushing to reach the battlefield when the next war broke out.

German, British, American, and Japanese forces ingested large amounts of amphetamines during World War II, but nowhere did the drug’s use have a more long-lasting societal impact than in Japan. The Japanese imperial government sought to give its fighting capacity a pharmacological edge, and so it contracted out methamphetamine production to domestic pharmaceutical companies for use during the war effort.

The tablets were distributed to pilots for long flights and to soldiers for combat, under the trade name Philopon (also known as Hiropin). In addition, the government gave munitions workers and those laboring in other defense-related factories methamphetamine tablets to increase their productivity.

Japanese called the war stimulants “senryoku zokyo zai” or “drug to inspire the fighting spirits.” Defense workers ingested these drugs to help boost their output. In the all-out push to increase production, strong prewar inhibitions against drug use were swept aside. It is not difficult to understand why. As researchers such as political scientist Lukasz Kamienski have documented, total war required total mobilization, from factory to battlefield. Pilots, soldiers, naval crews, and laborers were all routinely pushed beyond their natural limits to stay awake longer and work harder. In this context, taking stimulants was seen as a patriotic duty.

Kamikaze pilots took large doses of methamphetamine, via injection, before their suicide missions. They were also given pep pills stamped with the crest of the emperor. These consisted of methamphetamine mixed with green tea powder and were called Totsugeki-Jo or Tokkou-Jo, known otherwise as “storming tablets.” Most kamikaze pilots were young, often only in their late teens. Before the injection of Philopon, the pilots undertook a warrior ceremony in which they were presented with sake, wreaths of flowers, and decorated headbands.

Although soldiers from many countries returned home from the war with amphetamine habits, the problem was most severe in Japan, which experienced the first drug epidemic in the history of the country. Many soldiers and factory workers who had become hooked on the speed during the war continued to consume it into the postwar years, when it was easy to get the drugs because the Imperial Army’s post-war surplus was dumped into the domestic market.

These stockpiles of the drug then brought about other dramatic changes in Japanese society. Upon surrendering in 1945, the country had massive stores of Hiropin in warehouses, military hospitals, supply depots, and caves peppered throughout its territories. Some of the supply was sent to public dispensaries for distribution as medicine, but the rest was diverted to the black market rather than destroyed. There, the country’s Yakuza crime syndicate took over much of the distribution, and the drug trade would eventually become its most important source of revenue.

Pervitin, a methamphetamine brand that German soldiers used during WWII, dispensed the tablets in these containers. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Any tablets not diverted to illicit markets remained in the hands of pharmaceutical companies. In the wake of the traumas and dislocations of the war, a depressed and humiliated population offered an easy target. As Kamienski noted, “The pharmaceutical industry advertised stimulants as a perfect means of boosting the war-weary population and restoring confidence after a painful and debilitating defeat.” The drug companies mounted advertising campaigns to encourage consumers to purchase over-the-counter medicine sold as “wake-a-mine.” The product was pitched as offering “enhanced vitality.” In No Speed Limit: The Highs and Lows of Meth, journalist Frank Owen reports that these companies also sold “hundreds of thousands of pounds” of “military-made liquid meth” left over from the war to consumers, who did not need a prescription to purchase the drug.

With an estimated 5 percent of Japanese people between the ages of 18 and 25 taking the drug, many became intravenous addicts in the early 1950s.

Another driver of the epidemic was the existence of large, new U.S. military bases on the islands, which had never previously been occupied by a foreign power. National newspaper Asahi Shinbun wrote that U.S. servicemen were responsible for spreading amphetamine usage from large cities to small towns. Indeed, the Japanese government’s Narcotics Section arrested 623 American soldiers for drug trafficking in 1953. However, according to historian Miriam Kingsberg, most drug scandals involving U.S. soldiers garnered little coverage by the major papers out of “deference” to “American-Japanese friendship.”

Surging methamphetamine use led to increasingly strict state regulation of the drug: The 1951 Stimulant Control Law banned methamphetamine possession, and penalties were increased three years later. But these increases did not stop the rise in arrests for amphetamine abuse, which jumped from 17,500 people in 1951 to 55,600 in 1954. During the early 1950s, arrests in Japan for stimulant offences made up more than 90 percent of total drug arrests.

In an anonymous survey by the Ministry of Welfare in 1954, 7.5 percent of respondents reported having sampled Hiropon. Meanwhile the Asahi Shinbun published an estimate that 1.5 million Japanese were methamphetamine users in 1954, out of a total population of some 88 million.

The high rates of amphetamine use in Japan started to subside by the late 1950s and early 1960s, once economic growth began to create more jobs. Nevertheless, methamphetamine would remain the most popular illicit drug in Japan for decades to come.

Send A Letter To the Editors