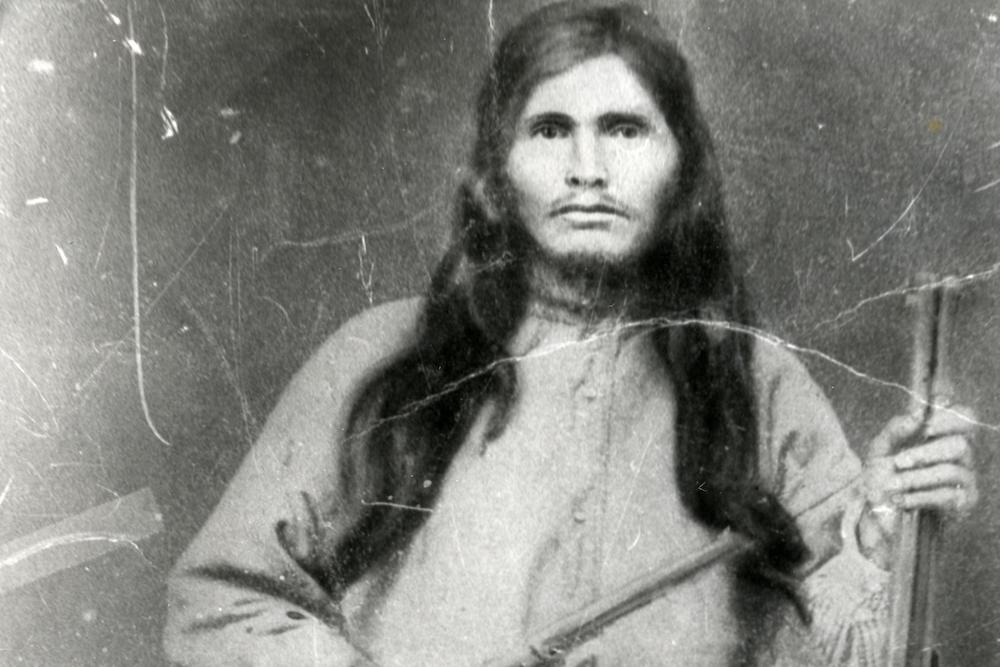

Cherokee National Councilman Nede Wade “Ned” Christie was a skilled sharpshooter and father of four who could imitate a turkey gobble loudly and accurately. Courtesy of FortSmithNPS/flickr.

On the spring evening in 1887 that he arrived in Tahlequah, the capital of the Cherokee Nation, U.S. Deputy Marshal Dan Maples was fatally shot in the chest by an unknown assailant hiding in dense brush. Murders, rapes, and thefts occurred almost daily in post-Civil War Indian Territory (later the state of Oklahoma), and the death of Maples was hardly surprising.

Also unsurprising was the mythology that grew around the supposed assailant and the lawmen who pursued him, for those stories served white narratives about Indian Territory and the American West.

Who was responsible for the deputy marshal’s death? Several miscreants with criminal backgrounds were summoned to the U.S. District Court of Arkansas at Fort Smith. Each man swore to the judge that he did not kill Maples and mentioned that 35-year-old Nede Wade “Ned” Christie, a Cherokee National Councilman, was in the area at the time of the crime.

Christie, as everyone knew, was a traditionalist Keetoowah who lost family members on the Trail of Tears. He often vocalized his strong distrust of the U.S. government and his animosity toward the thousands of white intruders who swarmed illegally onto Cherokee lands.

Surprised and angered at his indictment, Christie refused to travel to Fort Smith. The judge interpreted his action as an admission of guilt and Christie became the prime suspect.

Christie resigned from the Cherokee National Council. For the next five years, he and his family lived quietly at his Wauhillau home in the lush forests of the Ozark Mountains foothills. On several occasions a posse intent on avenging the death of Maples attempted to capture him. But Christie, a skilled sharpshooter, rebuffed each sortie, reportedly letting out a turkey gobble before each shot (Christie, his family says, was talented at imitating the gobble and could do it quite loudly).

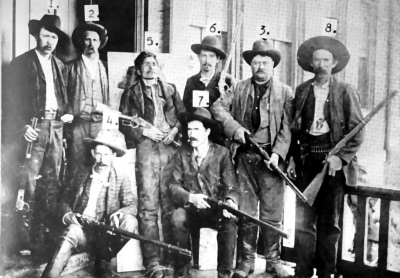

Finally, on November 3, 1892, a determined posse destroyed Christie’s log cabin with dynamite in an explosion so loud some residents claimed they heard it 30 miles away. Christie’s wife, stepson, daughter, son, grandson, and teenaged cousin Arch Wolfe escaped through a floor trap door. The posse members shot Christie as he charged out of his burning house, firing his pistols. The jubilant lawmen strapped Christie’s body to a door and displayed it before gawkers at Fort Smith for three days before releasing the corpse to the grieving Christie family.

U.S. Deputy Marshals pose with the corpse of Ned Christie in November 1892. (1) Paden Tolbert (2) Capt. G.S. White (3) Coon Ratteree (4) Enoch Mills (5) deceased Ned Christie (6) Thomas Johnson (7) Charles Copeland (8) Heck Bruner. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In death, Ned Christie became a legend.

Christie was no reprobate. There is no evidence that he killed Maples. Nor did he ever rob a bank, much less murder dozens of lawmen, women, and children, as some publications alleged. Granted, he was known to drink, had a reputation for using weapons that he made himself, and was prone to outbursts of anger—such as the time he shot a man after he insulted Ned’s mother by calling him a son of a bitch.

Ned Christie also played a crucial role as Cherokee Councilman in amending and repealing acts and laws, protecting tribal natural resources, and assessing lists of men desirous of marrying Cherokee women and therefore gaining access to tribal assets. His traditionalist Keetoowah family was a large and respected one. His father, Watt, and several brothers also served on the Cherokee tribal council. Ned had married several times, the last woman being Nuci Goie (Nancy), and he was a loving father to four children.

None of Christie’s positive attributes mattered to the newspapers. Within hours of receiving the telegraphed news of Christie’s death, hundreds of newspapermen across the country began creating fantastical, unsubstantiated, and often absurd stories about the deceased “notorious outlaw and terror of the Indian Territory” who “possessed a deadly hatred for Deputy Marshals.” The timing of Christie’s death was perfect for those writers seeking profit-making headlines. Lawmen involved with Christie’s death gave reporters outlandish personal mythologies casting themselves as heroes. No one really knew who fired the killing shot, but many marshals and deputies claimed they were the ones who dispatched Christie.

The exaggerated stories about both Christie and his pursuers did share one commitment—to ideas of manliness. By 1892, the last tribes had been sent to reservations, white settlements had been established from coast to coast, the bison were almost gone, and the wilderness was quickly diminishing. Readers craved exciting stories about the vanishing frontier, and the Christie story includes every Wild West theme: violence, forbidding wilderness, sharpshooting, moral righteousness, vengeance, stabbings, drunken escapades, beheadings, and tar and featherings. Women—who are usually present to bolster manly narratives—are portrayed in the Christie mythologies as cackling squaws.

The image of Ned Christie as a psychopathic outlaw who had to be killed by masculine lawmen may have been fabricated, but it has never gone out of style. In the ensuing years, whites continued to clamor for Indian land, and the maligning of Christie, their political opponent, suited them just fine. In the 1960s, the manufactured Christie saga even had a revival, as subject matter for Wild West magazines, western movies, and television shows featuring formidable models of manhood such as John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, and Chuck Connors. No detail about Christie was beyond exaggerating. In 1967, C.H. McKennon penned the energetic, but mostly contrived Iron Men: A Saga of the Deputy United States Marshals Who Rode the Indian Territory, which described Christie as being at least 6-foot-4. In reality, Christie was at the most 5-foot-8.

For the next two decades, writers used the new stories created by McKennon as they manipulated information and fabricated tales demonizing Christie and bolstering the lawmen who killed him. As late as 2015, Dave Farris composed a piece about the Christie saga in the Edmond, Oklahoma, local paper Edmond Life and Leisure that virtually duplicated every sensationalistic, unconfirmed report about Christie’s life.

Fake news about Christie has also appealed to those espousing his innocence. A nonsensical 1918 story in the Daily Oklahoman—stating that a witness swore he saw who killed Maples and it was not Christie—has long been hailed as the piece that exonerates Christie, despite its obvious fabrication. In 2015, the Cherokee Nation even financed a short video using that flawed story as proof of his innocence. The evidence that vindicates Christie is actually contained in the court documents, testimonies of the people in town that evening, time lines, and the behavior of all involved. John Parris, a repeat offender who left Indian Territory in 1891, was the culprit.

Those who have benefited from Ned Christie’s story have never cared about Christie’s family, career, tribe, or his possible innocence. Nor have they shown regard for how their words impacted Christie’s surviving family members.

The libel against Christie contributed to the tragic fate of Arch Wolfe. Wolfe was not present at Christie’s death, but he was sentenced to 24 months for assault with intent to kill. He later garnered two more sentences of 18 months each for selling whiskey. Arch would never again see the Cherokee Nation. After two years in prison, he was sent to the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C., then to the wretched Canton Asylum for Insane Indians in South Dakota (also known as Hiawatha Asylum) where he died at age 39. President Cleveland had denied him clemency, no doubt influenced by the bad press and Wolfe’s association with his cousin Christie, the “outlaw.” After the Asylum was razed in 1975, the city of Canton created the Hiawatha Municipal Golf Course. The Canton cemetery is situated between the fourth and fifth fairways. Arch is one of the 121 inmates buried there.

A year after Christie’s death, his son James was found dead, nearly decapitated, on the side of a road. Christie’s widow, Nuci Goie, married Ned’s brother Jack and after her death and the deaths of her children they were buried in the Jack Christie family cemetery. That land was sold to a white family, who later bulldozed all of the Christies’ caskets, bodies, and headstones into a lake.

Send A Letter To the Editors