Illustration by Be Boggs.

After he escaped from slavery in Baltimore in early September 1838, Frederick Bailey was broke, homeless, and scared. As he huddled among barrels in New York City’s Chambers Street dock, the man who later became known as Frederick Douglass worried about slave catchers and rats. Suddenly a large black man wearing a stove pipe hat, spectacles, and a formal jacket and pants emerged and invited Douglass to his home at 36 Lispenard Street, just a few blocks away.

Douglass’ savior was none other than David Ruggles, a free black man who was the secretary and general organizer of the New York Committee of Vigilance or NYCV, an abolitionist organization that battled slave catchers, kidnappers, and slave traders—and offered succor to hundreds of self-liberated people.

David Ruggles was arguably the first full-time black activist in the United States. He operated New York’s first library and bookstore for black people, edited and sold newspapers and magazines, and founded a black high school and a literary society. An innovator, he combined his activism with commerce by operating a grocery that only sold products made without enslaved labor. Over the course of his life, Ruggles was a true 19th-century Renaissance Man, a visionary political leader, a savvy street fighter, and a healer. He didn’t share Frederick Douglass’ fame or good fortune, but he was an indelible influence on the younger man—crucial to forging the legend that Douglass was to become.

In his 1845 narrative and in subsequent writings, Douglass used capital letters when he credited Ruggles with saving his freedom. He wasn’t being hyperbolic. Having fled from slavery in Maryland, Douglass was highly vulnerable to slave catchers or “black birds” who preyed upon northern African Americans, seizing them to exchange for cash and shipment into perpetual bondage in the South. During Douglass’ first 10 days out of enslavement, it was Ruggles’ home he stayed in as he launched his life as a free man. There Douglass married his fiancé, Anna Murray, in a ceremony at Ruggles’ house officiated by Reverend James W. C. Pennington, who escaped from slavery himself in 1828 and now served as pastor of the First Congregational Church of Hartford, Connecticut.

During his stay on Lispenard St., Douglass also absorbed Ruggles’ passion and erudition, receiving a crash course in radical abolitionism. Ruggles’s home, it’s important to note, was ground central for the Underground Railroad on the East Coast, and there Douglass met dozens of self-emancipated men and women passing through. He watched from a court gallery as Ruggles became one of the first black men to act as a lawyer in an American court, cross-examining a white man during a trial. Douglass watched Ruggles produce an issue of the nation’s first black magazine, the Mirror of Liberty, from his store—and absorbed an important piece of wisdom from his new mentor: writing was fighting.

After those 10 tumultuous days, Douglass and his new wife headed off to Underground Railroad operators in New Bedford, Massachusetts, known as the Fugitive’s Gibraltar, where Douglass soon began his own career as an activist. Ruggles had sent the couple on their way with a letter of recommendation and a five-dollar bill that, along with many others he dispensed to freed men, was to cause him great trouble later on.

Ruggles was born in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1810 to freeborn parents, David, Sr., a woodcutter, and Nancy, a famed caterer. As a child, he was an excellent student, and his school imported a Latin tutor to work with him. If Ruggles had been white, perhaps he would have studied at Yale, become a Congregational minister, and achieved public leadership in church and politics. But Ruggles was black—and eager to subvert authority as he led. The young man joined the anti-slavery movement in 1828 under the mentorship of the Rev. Samuel Eli Cornish, editor of the Freedom’s Journal, America’s first black newspaper. Ruggles made his first waves as an activist when he hired self-emancipated black people at a grocery shop he had opened in New York City in 1827. Arsonists burned the store down, twice.

Undeterred, Ruggles became an agent for the abolitionist Liberator and Emancipator newspapers, canvassing for subscriptions in the Mid-Atlantic and New England regions. He attended the black conventions that were held annually in the 1830s, representing younger, militant African American New Yorkers. A vast number of editorials and pamphlets he authored reveal his thinking: In 1835 letters to the Emancipator, for instance, Ruggles decried free black indifference to the anti-slavery cause. Spending money on tobacco and alcohol instead of subscribing to the newspaper, he wrote, showed a lack of manhood. Free blacks should help battle the American Colonization Society, a national scheme that proposed forced exile of free blacks to Africa on the basis that perceived inferiority disqualified them to be American citizens.

Ruggles battled for what he termed “practical abolitionism.” In a famous speech in 1835, he proclaimed that slavery’s end was a noble goal, but blacks had to fight other inequities too. He urged them to resist the slave catching gangs that roamed New York City streets, seizing black people who, they claimed, might be fugitives. Corrupt magistrates, viewing black people as property without rights, quickly spirited the accused off for sale into slavery. Ruggles castigated kidnapping and argued that every person had the right “to resist unto death.”

Around that time, Ruggles helped found the NYVC, which litigated court cases to help formerly enslaved people and to thwart slave traders. The organization quickly became the template for dozens of similar societies and earned renown among self-emancipated slaves from Virginia north.

Ruggles strongly believed that women were a key part of the abolitionist movement. He authored a pamphlet, “The Abrogation of the Seventh Commandment,” in which he demanded that northern women shun their southern sisters who, by their silence, accommodated the rape of enslaved black women by their husbands, sons, and brothers. At his store, Ruggles proudly displayed the published work of Maria Stewart, a pioneering African American poet and lecturer. Perhaps most importantly, Ruggles got as many as a thousand New York City black women to buy subscriptions to the newspapers he represented. These women became the eyes and ears of the movement.

Politics amongst the abolitionists were often fierce and divisive. Soon after Douglass’ departure for New Bedford, Ruggles became embroiled in a libel case that resulted in an acrimonious dispute with Cornish, now editor of the Colored American, the nation’s leading black newspaper. The argument led to an examination of the Vigilance Committee’s financial books. Under audit, Ruggles could not account for the numerous $5 bills he had given to self-emancipated people like Douglass.

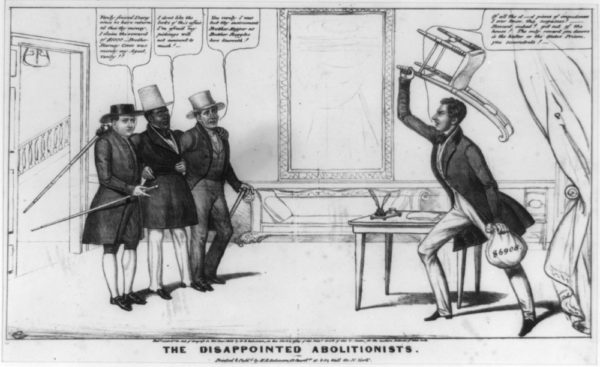

David Ruggles stands between two men in this 1838 lithograph by Edward Williams Clay about the Darg trial. The texts above their heads read, left to right: “Verily friend Darg since we have returned thee thy money, I claim the reward of $1000 – Brother Barney Corse was merely my agent, verily!” A second man says: “Yea verily I was but thy instrument Brother Hopper as Brother Ruggles here knoweth!” Man at right, holding bag marked $6908, tells them to “get out of the house.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Because of that Ruggles was drummed out as secretary of the Vigilance Committee. He continued to edit pamphlets, articles and the Mirror of Liberty, but before long was beset by blindness, stomach worms and other maladies. Half-dead, he roamed New York and New England, attending dinners thrown in his support by admiring young activists such as black radicals Pennington and William Wells Brown, white radical Charles Torrey. Ruggles also got support at one such dinner from Douglass, who introduced him, read passages from the Mirror of Liberty, announced that he was becoming an agent for the magazine, and pledged to raise $50 to support Ruggles and his journalism.

Ruggles continued to fight through deeds and in the field of ideas. In the early summer of 1841, during a fund-raising trip, he was evicted from his seats on a railroad car and steamship journey after he refused to retreat to the sections reserved for black passengers. “While I advocate the principals of equal liberty, it is my duty to practice what I preach,” he declared.

During a similar confrontation over seating a few weeks later, Ruggles was tossed off a moving train, got badly injured, and lost his valise and money. He sued the railroad—unsuccessfully—and the judge’s determination that the company had the right to assign seats caused an uproar among abolitionists. Again, Frederick Douglass led a meeting to protest the decisions, which was attended by Ruggles and white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, a great mentor to Douglass.

Soon after, Ruggles, Douglass and Garrison sailed to a meeting on Nantucket. When the ship’s crew informed black passengers that they could either move to the windy upper deck or get off the boat, Garrison joined his African American comrades. Then, on Nantucket, Douglass gave a series of speeches that electrified his audiences and jumpstarted his career.

As Douglass’ star ascended, Ruggles’ fortunes wobbled. By 1841, Ruggles was practically homeless—abolitionist allies in Massachusetts wound up taking him in—and his health continued to decline. By his own account, he had consulted many eminent physicians and had been repeatedly “bled, leached, cupped, plastered, salivated, doused with arsenic, nuxvomica, iodine, strychnine, and a variety of other poisonous drugs,” to no avail. Then, in 1842, Robert Wesselhoeft of Cambridge, Massachusetts, who practiced hydrotherapy, also known as the water-cure, put Ruggles through a series of rigorous protocols, including weeks of early morning cold showers and full body wraps in cold sheets and bandaging.

Ruggles’ health improved. Enthused, he decided to study hydrotherapy, devoting two years to learning the medical practice. He began composing articles on the water cure for professional journals. He borrowed money from local white businessmen to build a small hydrotherapy hospital in Florence, a village near Northampton. The establishment had 15 beds, and multiple showers and bathing rooms.

Frederick Douglass paid a visit to Northampton in 1844 and met with Ruggles. By then Douglass was a star on the abolitionist lecture circuit, accompanying the famed Hutchinson Family Singers. Douglass, Ruggles, and the singers had a lively time together—some critical observers even noted that the young Abby Hutchinson, one of the singers, “was gallanted to her hotel by one of the members, and he a huge black man.” Ruggles sarcastically identified himself as the escort and noted that he was close friends with leading New York City merchants.

Over the next few years, David Ruggles expanded his career in hydrotherapy, while Frederick Douglass became the most famous abolitionist in America. With Ruggles’ help, Florence became the center of a growing community of free and self-emancipated blacks, including the abolitionist Sojourner Truth and her three daughters, and Basil Dorsey, who had been rescued from a slave catcher in Philadelphia. When Douglass stopped by Florence again in 1845, he was impressed: “There was no high, no low, no masters, no servants, no white, no black,” he wrote, of the community. Douglass also noted that Ruggles was grateful to “these noble people.”

The men stayed in contact. Ruggles was an early subscriber to Douglass’ North Star newspaper in 1848; Douglass, in turn, convinced Ruggles to vote for the Free Soil party ticket in 1848. Hydrotherapy, sadly, did not cure Ruggles’ many ailments and he died, after a short, virulent sickness, on December 16, 1849, at the age of 39.

Douglass wrote a glowing obituary in the North Star. In his second autobiography, published in 1855, Douglass recalled “Mr. Ruggles as the first officer of the under-ground railroad with whom I met after reaching the north, and indeed, the first of whom I heard anything,” an indication that Ruggles’ name was known to many a fugitive slave. Douglass repeated his praise of Ruggles in his 1882 autobiography, revealing his lifelong indebtedness to that “whole-souled man.”

Send A Letter To the Editors