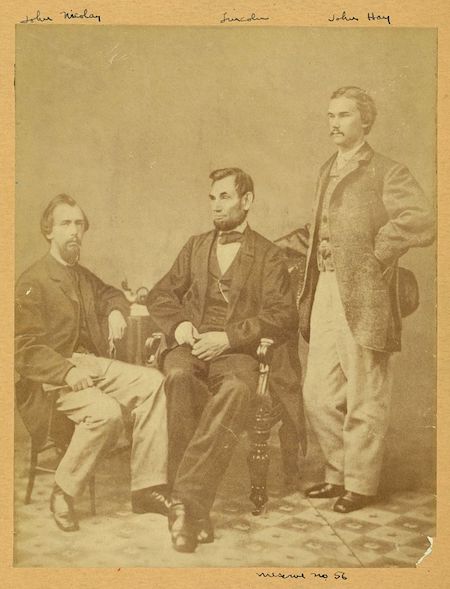

John George Nicolay served as Private Secretary to President Abraham Lincoln, becoming the de facto first White House chief of staff. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Less than a month after dark horse candidate Abraham Lincoln won the new Republican Party’s presidential nomination at its convention in Chicago, on May 18, 1860, he made a decision that would impact his campaign, his presidency, and his image for generations to come: He asked a 28-year-old German immigrant named John George Nicolay to be his campaign secretary.

Nicolay, who eventually became Lincoln’s private secretary, may not be well-known today, but he was one of the most significant people working behind the scenes in the Lincoln administration and his efforts on behalf of the 16th president changed the course of American history. Possessed of organizational skills that Lincoln lacked, Nicolay managed White House operations and protected Lincoln’s time, allowing the president to become perhaps the nation’s most active and involved wartime commander-in-chief. Nicolay was devoted to Lincoln and his friendship eased the president’s burdens during the terrible ordeal of civil war. Following Lincoln’s assassination, Nicolay and his friend John Hay worked for years on a massive biography of Lincoln that shaped the president’s image as the good and wise Father Abraham who saved the Union, ended slavery, and gave America renewed freedom. Nicolay helped Lincoln achieve greatness in both life and legend.

Born Johann Georg Nicolai in 1832 in the village of Essingen in what is now Germany, Nicolay was five when his family arrived in the United States, anglicized its last name, and settled in a German immigrant community in Cincinnati, Ohio. When Nicolay’s mother died soon thereafter the family left for a series of western locations, eventually settling in Pike County, Illinois, where they operated a grist mill. While physically frail, the academically inclined George, as he was called, learned English quickly. By the age of 14 he had lost his father and been dismissed from the family mill by his eldest brother. But he soon landed a job at the Pike County Free Press in Pittsfield, the county seat of Pike County, Illinois.

Lincoln at the time was a circuit-riding attorney who often argued cases in the Pike County courthouse, across the street from the newspaper’s offices. Nicolay followed Lincoln’s court appearances and budding political career with growing interest and enthusiasm. Like Lincoln, Nicolay was drawn to the new Republican Party, which opposed slavery’s expansion. And like Lincoln, he was vehemently opposed to Senator. Stephen A. Douglas’s 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which negated the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and permitted slavery anew in territory that had been closed to it.

At the Free Press, Nicolay worked his way up from printer’s apprentice to reporter to sole proprietor. The paper supported Republican candidates in Illinois, including Ozias M. Hatch, who after his election as Secretary of State in 1856 invited Nicolay to become his chief clerk. After selling the newspaper, Nicolay moved to Springfield to join Hatch’s staff in 1857. While executing his duties at the state library and election archives, located directly across the street from Lincoln’s law office, Nicolay finally got to meet Lincoln in person. Although Lincoln was 23 years older than Nicolay they became fast friends, often conversing and playing chess in the State Library.

In 1858, Lincoln ran for Douglas’s senate seat, engaging in the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates that cemented his reputation as a moderate and reasoned anti-slavery voice within the Republican Party. He lost the race, but Republican leaders decided that transcripts of the debates should be published and distributed nationally to promote the party’s cause. Lincoln called on Nicolay to hand deliver the copies to a publishing company in Ohio, writing in his letter of introduction, “Mr. Nicolay is a good Republican … a good man and worthy of any confidence that may be bestowed upon him.” Given these sentiments, it didn’t take long for Lincoln and Nicolay to forge a partnership in politics.

Lincoln’s star was on the rise. Many Republicans thought he’d make a great vice presidential candidate in the 1860 election, but he and Nicolay envisioned something more. In February, 1860, Nicolay began pushing Lincoln’s prospects for a presidential run, writing an editorial endorsing Lincoln for president in the Pike County Free Press. Nicolay was present at the Chicago convention when Lincoln won the nomination. Soon thereafter, Lincoln offered him the position of campaign secretary.

Lincoln liked Nicolay and admired his abilities, but there was also a political calculation in choosing a widely respected German immigrant to play a key role in his administration. German American voters had been alienated by the Democratic Party’s defense of slavery, as well as by the American (or “Know Nothing”) Party and its anti-immigrant positions. When the “Know Nothings” merged into the coalition forming the new Republican Party, German American voters were unsure where they belonged. By appointing Nicolay his private secretary, Lincoln assured German Americans that he was not a nativist.

As the Private Secretary to the president, Nicolay became the de facto first White House chief of staff. He brought his friend Hay on board as an assistant. Nicolay served as a gatekeeper of access to Lincoln, coordinating daily White House routines that included managing the president’s schedule, handling correspondence, and even ordering filing cabinets for proper storage of the administration’s paperwork (no longer was Lincoln allowed to carry around important documents in his hat). Nicolay served as the principal liaison between the White House and Congress. He sat in on Cabinet meetings and presidential interviews and took careful notes. He drafted important documents and letters. He assisted First Lady Mary Lincoln with state dinners and other matters of protocol, experiencing tense relations with her when she overspent and fudged the accounts. Nicolay and Hay were Lincoln’s sounding boards as the president conducted business in D.C. and went on missions to various parts of the country beyond as the president’s trusted eyes and ears. Nicolay conducted multiple treaty negotiations with Native American tribes. His organization of the president’s schedule freed Lincoln to spend critical hours each day in the War Department’s telegraph office monitoring developments in the field. Without Nicolay’s focus, Lincoln could have been lost in a sea of detail.

President Abraham Lincoln sits between John George Nicolay (left) and John Hay (right) in Washington, D.C., in November 1963. Hay wrote in his diary, “We had a great many pictures taken … Nico & I immortalized ourselves by having ourselves done in a group with the Prest.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Nicolay continued working for Lincoln through the president’s 1864 election to a second term, but decided he wanted to depart the White House shortly thereafter. Living in Washington had meant enduring long periods of separation from the love of his life, Therena Bates, who remained in Pittsfield, and Nicolay was growing weary of confrontations with Mrs. Lincoln. He accepted Lincoln’s offer of an appointment as American consul at Paris, but was still in his White House job—returning from a mission to Cuba—when he learned that the president had been assassinated. Devastated, he remained in his secretary post until he and Hay had organized Lincoln’s presidential papers and made the presidential office ready for Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson.

Nicolay and Bates got married and headed off for a new life in Paris in June of 1865. Their daughter, Helen, was born there the following year. Nicolay served as consul at Paris until he was replaced by an appointee of President Grant in 1869. He returned to the U.S. and became a naturalized American citizen on October 12, 1870. (Apparently no one, including President Lincoln, had known that Nicolay wasn’t a citizen.) In 1872 he was selected to be Marshal of the U.S. Supreme Court. This enabled Nicolay and his family to live in Washington, D.C., and allowed him to begin the legacy-cementing literary work he really wanted to do: prepare a history and biography of Abraham Lincoln and his era.

Nicolay and Hay worked with Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s son, who gave them access to Lincoln’s presidential papers. Doing painstaking research, Nicolay and Hay shunned hearsay and undocumented tales about Lincoln and relied on credible documentation for every aspect of their 10-volume, 4,800-page work, Abraham Lincoln – A History, which was published by the Century Company in 1890. The work was more than a mere biography of Lincoln. It assembled a detailed military history of the Civil War and reported on the machinations of the cabinet, Congress, and the military. It portrayed Lincoln as a witty and wise man who loved to tell stories. It detailed how Lincoln bore the suffering of war on his shoulders while his faith in God grew deeper, and the ways he saw beyond the immediate ups and downs of war, keeping the ultimate goal of preserving the Union ever in his mind. It was the first scholarly validation of the president’s greatness and became the foundational work for all the scholarly writing on Lincoln to follow.

This massive effort was not viewed as flawless, but it was widely praised when it was published, and it shaped a heroic image of Lincoln that persists to this day. In Nicolay and Hay’s telling, Abraham Lincoln could do no wrong. His motives were always pure, his fairness, kindness, and wisdom were without parallel, and only he possessed the qualities of mind and character needed by the nation in its moment of gravest crisis. The book was a work of filial love, scholarly yet biased, by two men who, in their early manhood, had viewed Lincoln as an all-wise father figure who could do no wrong, the man who had saved the nation and ended slavery.

The self-effacing Nicolay—the Father of Lincoln Scholars—is practically invisible in the volumes. He always chose to work behind the scenes for his hero, mentor, and friend.

Send A Letter To the Editors