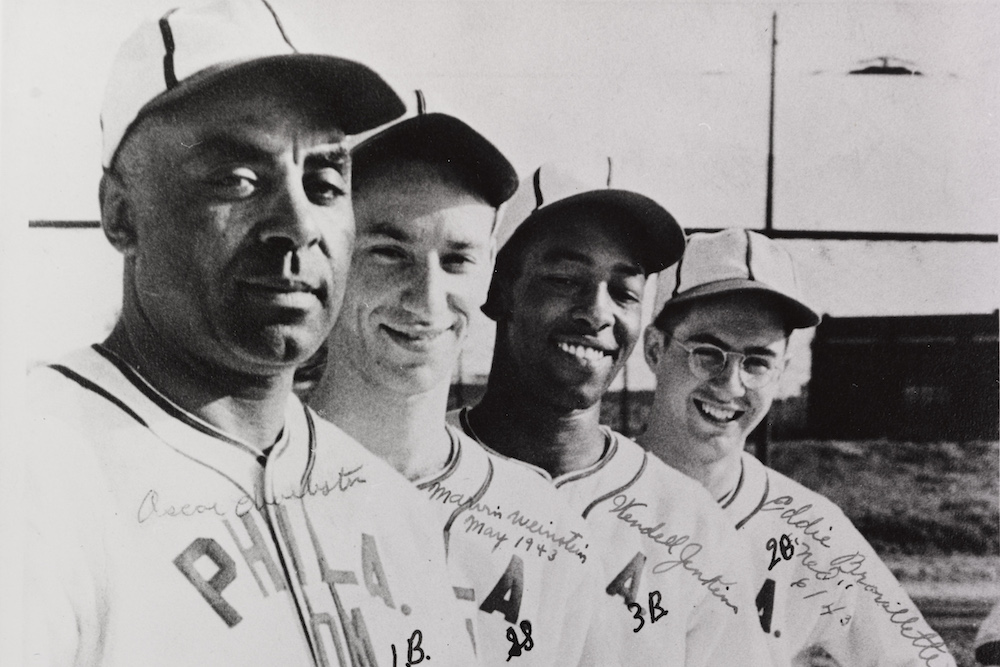

Oscar Charleston was a standout ballplayer and barrier-busting sports pioneer. His achievements, many long forgotten, include managing and playing for the Quartermaster Depot’s integrated baseball team in Philadelphia. The team’s 1943 infield—Marvin Weinstein, Wendell Jenkins, and Eddie Brouillette—are pictured here, with Charleston at left. Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

History, more often than we would like, is an unjust judge. Consider the case of Oscar Charleston, a baseball player who for nearly 40 years was one of the most talented, charismatic, and profoundly intense competitors in the Negro Leagues.

Today, almost no one—including serious baseball fans—knows the slightest thing about Charleston, despite the fact that he arguably pieced together the best overall résumé of any figure in baseball’s storied history.

That résumé has three basic components: First, Charleston was a stupendously good player—so good that in 2001 the celebrated baseball analyst and historian Bill James rated him the fourth-greatest player of all time, behind only Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, and Willie Mays. Second, Charleston was a highly successful manager. He won three Negro Leagues championships as a manager and in one poll of ex-players was named the greatest skipper in the leagues’ history. And third, Charleston was a trailblazing scout—probably the first African American ever to be paid to scout for a Major League Baseball club.

Off the field, Charleston was cheerful, charming, and widely revered. The most famous player in black baseball until Satchel Paige rose to superstardom in 1933 (who, it warrants mention, was one of Charleston’s protégés on the Pittsburgh Crawfords), Charleston was greatly interested in the world around him (he learned to speak and write Spanish in short order, for instance, while playing winter ball in Cuba) and also cared deeply about African American history and social progress.

But these facts about Charleston, who died childless in 1954, are mostly buried in old newspaper pieces, interview transcripts, and archives. His story, as it’s remembered today, is instead often overshadowed by an inaccurate (and racially stereotyped) perception that he was a hothead and a thug. That one of the most fascinating and admirable figures in the history of American sport could become so obscure and misunderstood not only illustrates the fickleness of history; it also points to how, 73 years after Jackie Robinson debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the legacy of the black baseball tradition has yet to be fully recognized.

The first professional black baseball team was formed in 1885, and it wasn’t long before the National League, the American League, and the Minor Leagues—so-called Organized Baseball—drew a firm color line and stopped allowing black players on their teams. As segregationist policies hardened, black baseball players and owners formed more of their own teams, grew their own (quite substantial) fan bases, built their own stadiums, and created their own institutions. The first black baseball association, the Negro National League, was launched in 1920 by the indomitable Rube Foster, manager-owner of the Chicago American Giants and a one-time black baseball star.

Over the next 20 years, several other leagues were launched, most notably the Negro American League, with major black teams from New York to Kansas City. Black fans followed the action in the pages of the era’s leading black newspapers, especially the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier. As in white America, baseball was unquestionably the African American community’s favorite sport.

And, for at least 15 years, that community’s favorite player was Oscar Charleston.

Charleston was born into a large, poor Indianapolis family on October 14, 1896. Raised primarily in the city’s vibrant Indiana Avenue neighborhood, he kept busy by playing sandlot ball and serving as a batboy with Indianapolis’s leading black ballclub, the ABCs. But in 1912, with family funds desperately low, Charleston, just 15 years old, lied his way into the Army. Shipped to the Philippines, he began his professional baseball career playing for the black 24th Infantry team in the Manila League. One of his teammates was another future Hall of Famer, Charles Wilber Rogan aka “Bullet Joe.”

Charleston was honorably discharged in 1915 and returned to Indianapolis, where he was signed by the ABCs. By the time Foster formed the Negro National League in 1920, Charleston was Blackball’s best player.

That at least was the claim of his contemporaries, and it is bolstered today by the rather good Negro Leagues statistics we now have at our disposal, thanks to a small army of volunteer researchers. Playing for the ABCs, the Harrisburg Giants, the Homestead Grays, and the Pittsburgh Crawfords, among other clubs, Charleston compiled the most hits, doubles, triples, RBIs, stolen bases, and walks in Negro Leagues history. He was second all-time in runs and home runs. Combine these achievements with his superlative defense in center field and his durability (Charleston was a full-time starter for 22 years, from 1915 through 1936), and he was first all-time, by far, in the advanced statistic of Wins Above Replacement, which combines offensive and defensive contributions into one number.

Charleston also played 10 seasons of winter ball in the strong Cuban League, finishing with a career batting average of .349 and gaining lasting fame as the best player on the 1922–23 and 1923–24 Santa Clara Leopardos, the team most often nominated by baseball historians as the best in prerevolutionary Cuban history.

How might Charleston have fared in the pre-integration “majors”? Probably very well. We know that he posted even better numbers when he took on major leaguers, whom he, like virtually every other black star in his generation, encountered regularly in exhibition contests. Hall of Fame pitchers Lefty Grove and Walter Johnson both gave up memorable home runs to Charleston.

Charleston’s contemporaries, white and black, revered him. Consider the judgment of famed shortstop Honus Wagner: “I’ve seen all the great players in the many years I’ve been around and have yet to see any greater than Charleston.” Or Cardinals scout Bennie Borgmann, who called Charleston the “greatest ball player I’ve ever seen.” “When I say this,” Borgmann said, “I’m not overlooking Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, and all of them.” Even Kansas City Monarchs co-owner Tom Baird didn’t let his membership in the Ku Klux Klan keep him from acknowledging that “Oscar Charleston was the greatest ball player that ever lived.”

More testimonies came from people like Major League Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler, who stated that Ty Cobb and Charleston were the greatest ballplayers he had ever laid eyes on. The Hall of Fame pitcher Dizzy Dean, born and bred in the Jim Crow South, captured Charleston’s greatness vividly: Charleston, he said, “didn’t have a weakness. When he came up, we just threw it and hoped like hell he wouldn’t get a hold of one and send it out of the park.”

Charleston’s striving for accomplishment was not confined to the baseball diamond. Throughout his life, he built up relationships with the powerful and famous, including Army musician and intelligence agent Walter Howard Loving; athletes like Jesse Owens and Jimmie Foxx; journalists Margaret Martin, Rollo Wilson, and Wendell Smith; and Negro Leagues owners Cumberland Posey and Gus Greenlee to name a few. Both of Charleston’s wives were accomplished women who came from prominent African American families, and the clippings about high black society that he pasted in his personal scrapbook suggest just how badly Charleston wanted membership in that rarified world.

Oscar Charleston—pictured in the top right, third from right—and his Quartermaster Depot Team. Courtesy of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Oscar Charleston photo album.

Charleston’s greatest social victories, however, came in breaking color lines. During World War II, as Brooklyn Dodgers president and general manager Branch Rickey was concocting his plan to outmaneuver rival teams by becoming the first to sign black players, Charleston was proving he could successfully navigate potentially fraught interracial situations by playing for and managing the integrated baseball team that represented his wartime employer, the Quartermaster Depot, in Philadelphia’s semipro Industrial League.

No wonder that the black Philadelphia Tribune printed a full-page spread on Charleston’s team in which it celebrated the “democracy” it displayed. One photo captures Charleston standing in front of three other players, two of them white. The display was powerful. After all, how many African Americans had managed a racially integrated ballclub in America or a racially integrated workplace by 1942? Another 19 years would go by before Gene Baker became the first regular black manager of a team in Organized Baseball when he took the reins of the Batavia Pirates.

In 1945, Branch Rickey got involved with a new black baseball league known as the United States League—and immediately gave Charleston a chance to break another barrier, bringing him in to manage the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers squad. Rickey viewed the Brown Dodgers as a way he could scout black players for the major league Dodgers without arousing suspicion among his competitors. Having Charleston as the team’s manager gave him a way to leverage the knowledge, insight, and connections of a man who knew everyone in, and everything about, the Negro Leagues.

Lead Dodgers scout Clyde Sukeforth would later emphasize the crucial role Charleston played in backgrounding potential Dodgers signees, including future Hall of Fame catcher Roy Campanella. For example, Charleston was able to assure a skeptical Rickey that Campanella’s reported age, 23 in 1945, was accurate. And Campanella recalled Rickey telling him that Charleston had “followed [him] around.” As a result, Campanella was “astonished” to “find out how much [Rickey] knew about me.” In all likelihood, Charleston also scouted John Wright, Roy Partlow, and Dan Bankhead, African Americans who were among the first six black men signed by Rickey’s Dodgers.

The scouting Charleston did for the Dodgers in 1945 came years before the work of black scouting pioneers like John Donaldson, Judy Johnson, and Quincy Trouppe—former Negro Leagues stars who, in their post-playing careers, worked for the White Sox, Athletics, and Cardinals, respectively. That makes it fair to suggest that Charleston may have been the Major Leagues’ first African American scout.

Charleston never got his moment playing integrated ball, but he helped others get theirs, as both a manager and a scout. As he told the Pittsburgh Courier’s Wendell Smith in 1954, “I never got the chance to play in the majors because of the color-line. Because of that, he said, he was committed “to see that these kids I’m managing get their chance. Everyone who goes up compensates in some way for me.”

Charleston died in a Philadelphia hospital shortly after that interview with Smith. Though he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976, his legacy did not get the attention it deserved in the years that followed. The decades after Charleston’s death were a fallow period for Negro Leagues history. To the rising generation of African Americans, the leagues seemed to suggest a too-ready acquiescence to Jim Crow, while, for obvious reasons, they troubled the conscience of white America. As a consequence, for two or three decades little historical work was done. Even now, in 2020, one can count on one hand the number of full biographies of players who spent their entire careers in the Negro Leagues.

Charleston, and the Negro Leagues as a whole, deserve better. Charleston put together one of the greatest careers in American athletic history—and he left an American legacy worth knowing. That few of us remember him is not his fault. It’s ours.

Send A Letter To the Editors