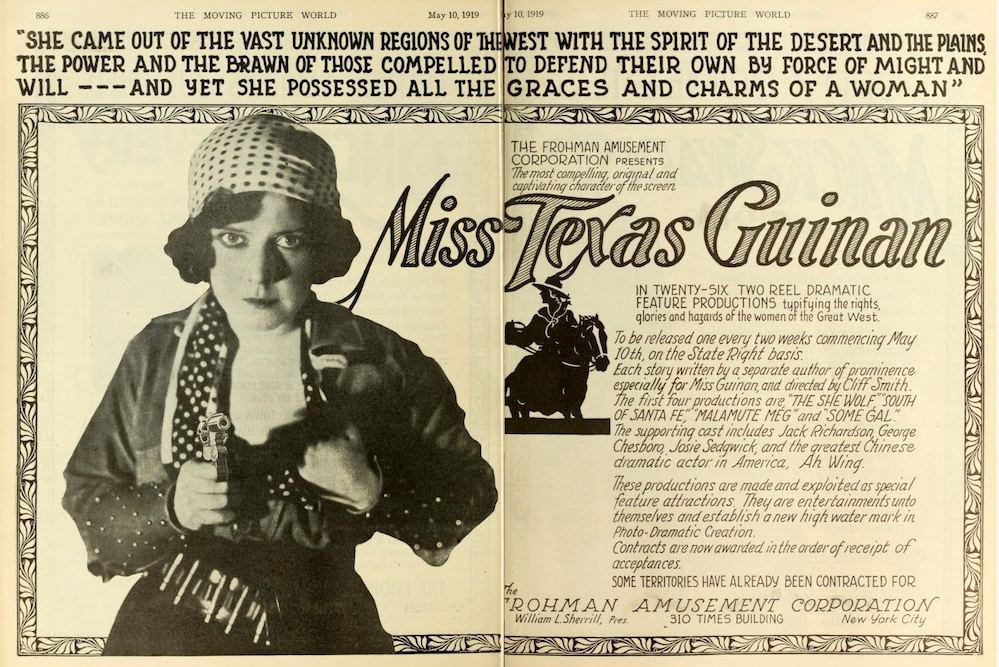

A 1919 advertisement in Moving Picture for films with actress Texas Guinan. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In an emotional scene, earlier this year actor Patrick Stewart stopped by “The View” to ask co-host Whoopi Goldberg to join the cast of “Star Trek: Picard” for its second season, and reprise the role she had played in “Star Trek: The Next Generation” back in the 1980s. Goldberg hadn’t been an original member of that cast either, although she was a longtime fan of “Star Trek.” In fact, she credited the series with sparking her interest in acting, mainly because it was the first time, she had not only seen “a beautiful black woman who was the communication officer” of a ship and not a housekeeper, but “black people in the future.”

If Goldberg was drawn to “Star Trek” because its cast included a powerful black woman of the future, in crafting a character for Goldberg on “TNG,” creator Gene Roddenberry conjured a name from the past. He named the bartender who blended mysticism with shrewd wit “Guinan,” after the once legendary Texas Guinan, a larger-than-life Texas girl turned emcee of some of the most exclusive speakeasies in Prohibition-era New York City.

Although Guinan may be forgotten today, her name was once as familiar as Whoopi Goldberg’s. Born Mary Louise Cecilia Guinan in 1884, Guinan took vaudeville by storm in her 20s, she starred in silent films in her 30s, and in her 40s, she was an influential impresario. An entrepreneur and a business woman, who ran nightclubs considered hubs of political and cultural power in New York City, Guinan alleged she was once thrown out of France for being too hot to handle.

Guinan grew up in Waco, Texas, where her parents ran a grocery before turning their hands to running a horse and cattle ranch. Her childhood consisted of riding horses, roping cattle, and shooting guns, skills that prepared her for a world of entertainment—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, pageants, and spectaculars—that was already beginning to disappear, just as she mastered it.

Promotional picture of Texas Guinan. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

After a brief stint in Colorado, Guinan moved to New York City, where she quickly found work in vaudeville. When a get-rich quick scheme involving a weight-loss scam went sour in 1913, Guinan left for Hollywood, performing in two-reelers, generally of the Roman-riding, gun-toting variety. Buxom, outspoken, already in her 30s, and by the standards of the day, old, it was hard to imagine Guinan as a damsel in distress. Judging from the look on her face and the set of her jaw in films and photos from the era, it was more likely that Guinan would make the outlaws rue the day they’d set eyes on her.

Guinan emceed in L.A. before returning to New York City, where she partnered with bootlegger Larry Fay, conducting business in their speakeasies perched at the center of the room, armed with a clapper and police whistle. While rumrunners sold pricy pints of whisky from back hallways, Guinan’s patrons listened to “her girls” sing and dance. Guinan, meanwhile, greeted customers with her trademark “Hello, suckers” or zippy one-liners like “You may be all the world to your mother, but you’re just a cover charge to me.”

Guinan flaunted Prohibition-era laws. Busted for violating the Volstead Act on more than one occasion, she defiantly wore a necklace made of tiny gold padlocks around her neck, an in-your-face statement against federal investigations and harassment. After she was found not guilty of violating the Volstead Act in 1927, federal agents—who had already condemned her as a “moral pervert”—dogged her footsteps, arresting her again the next year for violating a new curfew law.

Like many professional women, Guinan hungered for financial independence. Ambitious and independent, she refused to play by the rules of her era. And she wasn’t shy in expressing this desire. Of an actor she was involved with in Hollywood, Guinan recalled: “I should have taken him like Grant took Richmond. … I was the one woman who could take [him] and leave him where I found him. I was out to take not be taken. He taught me one thing, though, that the sweetest things in this life are obtained by the work of one’s own hands.”

At the time, men who were creating and curating media legends only saw the boobs and the busts and the bucks. But there was far more to Guinan’s story than that. An animal lover who refused to eat meat, Guinan was a teetotaler who never drank alcohol, preferring coffee. Despite her risqué reputation, she only married once, to newspaper cartoonist John J. Moynahan. When she wasn’t on the road, Guinan lived with her mother, father, brother, and pets in Greenwich Village.

To be sure, Guinan was no saint, but she was no “blonde bombshell” either. She was a New Woman, not in a Mary Pickford, girl with the curls kind of way, but with the moxie of a devoted New Yorker. Until Guinan broke into the nightclub business, emceeing was pretty much the exclusive province of men. Guinan opened doors for other women in burlesque and vaudeville, admiring women who also struggled to control their images and make headway as managers and owners. Guinan met Mae West in the teens, when they were struggling performers in New York’s vaudeville stagehouses, and they remained friends for the rest of Guinan’s life. She was frenemies with evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, alternately admiring and antagonizing her, and wanted to play McPherson on the big screen.

At a time when few women stood up to theater owners and producers, Guinan fought for pay equity. In 1928, she won a $26,000 award from Duo Art Productions, when the company was ordered to pay her the difference between the wages promised her for starring in the revue Padlocks of 1927 and the amount they actually paid her. When Guinan joined protests against the Mastick Law in 1930, which eliminated overtime for women working in factories and department stores, she told the crowd “the law was intended to keep women out of jobs in which they competed with men.” At 46, Guinan knew a thing or two about laws intended to exclude women from jobs reserved for men. When Guinan died unexpectedly of dysentery in 1933, 12,000 funeral goers came to the Campbell Funeral Church on Broadway. Women who came from very different walks of life but shared the experience of being paid less than men gathered to comfort each other.

Because of her outsized reputation and early death, there were some halfhearted efforts to turn her life into the stuff of legend. Shortly after she died, Guinan served as the basis for the character Maudie that Mae West played in Night After Night (1932). A film biography of Guinan’s life, starring Betty Hutton and titled Incendiary Blonde (1945), characterized her as a rough and tumble starstruck tomboy, enamored by the prospect of wearing a white gown with a sequined head dress, with two silver pistols at her side. Martha Raye starred in a musical flop based on Guinan’s life—Hello, Sucker!—in 1969. In 1995, Bette Midler said she’d been cast in “a star vehicle directed by Martin Scorsese about the legendary New York saloonkeeper Texas Guinan.” Mostly, these versions made Guinan’s story fit into one Hollywood loved to tell about women caught in its hungry star machine: they loved the sexism of Hollywood, they’d sell their very souls for stardom, they wanted it, they asked for it, even if what they were said to want ended more like Sunset Boulevard than It Happened One Night.

But in the mid-1950s, Guinan’s story had a chance at a different kind of telling when Vera Caspary began shopping a project based on the Texas girl turned emcee of some of the most exclusive speakeasies in Prohibition-era New York City. If Caspary’s name also has you scratching your head, that’s because hers is another that few other than film buffs or historians would recognize today. In the 1940s and 1950s, however, Caspary enjoyed successes of her own, as a bestselling novelist and prolific screenwriter. In fact, one of her trademark novels about independent-minded working girls was made into the Academy Award-winning film Laura.

Caspary was drawn to stories about women who had come before her, whose struggles had in part paved the way for her own successes. That made Guinan a natural choice for a project. Caspary, a fan of live entertainment, had, in fact, been a regular at Guinan’s clubs in the late 1920s, where she watched as Guinan “bawled at patrons to give each little girl a big hand.”

Though Guinan had been dead for nearly 25 years when Caspary started working on her story, she remained a touchstone for women eager to tell stories about women who had opened doors before them. In Caspary’s script, Guinan figures as a boss who refuses to let her “girls” be sexually harassed—“In my club no gentleman pulls a girl’s fringe without a license.” She wants love, but on her own terms. And she’s a “hard-headed business woman” who, when asked why she “can’t be a normal woman,” launches into a tirade:

Normal, huh! Listen, Mister, where I grew up the neighborhood was full of normal women. Good, normal women. Worked like dogs seven days a week. For what? On Saturday night a kick in the teeth from the drunken bums that called themselves normal husbands. No, thank you.

But by 1957, Caspary was forced to give up on the project. All her efforts to get a formal contract for “the Texas Guinan story,” she told producer Hal Stanley, “have been in vain.” At a time when film and television were narrowing the definition of what counted as a normal woman, it would hardly have done to have someone like Caspary—who held unorthodox views of her own—make a film celebrating another woman who had refused to put up with someone else’s definition of normal.

It’s a shame Caspary never had the chance to make her version of Guinan’s story. And while Roddenberry’s shout-out to Guinan in 1987 was a sweet Easter egg of a tribute for those who got the reference, this oblique nod to a hidden figure doesn’t really satisfy those who’d like to see more stories appear on the screen about those who struggled against sexism in the industry and onscreen in the past and who—even if it was for a fleeting moment—enjoyed some measure of success.

So when Guinan appears, perhaps behind the bar of the Ten Forward, on the next season of “Picard,” raise a glass in tribute to Texas Guinan and Vera Caspary and tell the person next to you about them. And while you’re at it, think about why—nearly a century later—we still know so little about Guinan, Caspary, and women like Gertrude Berg, Gypsy Rose Lee, Hazel Scott, Fredi Washington, Lois Weber, and others who worked to transform media industries and, in doing so, change the stories we tell about the past and the future.

Send A Letter To the Editors