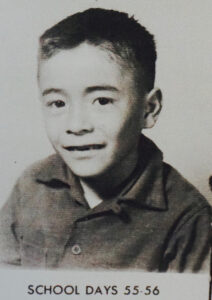

Writing while walking by Emilio Robles Kirkpatrick. Courtesy of Juan Felipe Herrera.

Juan Felipe Herrera is a writer, cartoonist, teacher, activist, and the 21st United States Poet Laureate. His numerous collections of poetry include 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border: Undocuments 1971-2007 and Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems. Before joining a Zócalo streamed event titled “What Can Poetry Offer Us in Distressing Times,” he called into the virtual green room to talk about the time of day that feels like walking in the breeze, what’s on his personal time travel itinerary, and using his full voice.

What did you have for breakfast this morning?

For breakfast this morning? Let’s see, I had an octagonal-shaped cut apple, and I had some interesting yogurt that’s kind of formless, and then I also had one of those feta cheese burritos [from Starbucks] that was pretty tasty. And then I had some passion lemonade with ice. Venti.

If you could time travel to any time, when would it be? And what would you like to do there?

I’d like to hang out with Buddha. That’s quite a shocker. Talk about really getting rid of all the furniture in your brain. I think if I met up with Buddha, it would definitely be a polinización. Clear mind, clear heart. That would be one of my serious responses.

I would also like to go back to the time of the trilobites, and see what trilobite life was all about. That would be interesting if I were to go as far back as 200 billion years. A little closer, I think I’d go back to—let me see. I’d like to go back to Charleston time. I sure would like to dance the Charleston. Or I’d go back to early Jimi Hendrix movimiento days. I’d get on stage with Jimi. I’d want to riff with Jimi.

Do you play any instruments yourself?

Yeah, I play the guitar. I haven’t played it in a while, but I play the guitar—and the harmonica, which I play more often than I play the guitar. When I was in high school, we still had the last vestiges of the coffee house days. Not that far from San Diego High School was La Mesa. In La Mesa, they had perhaps the last coffee house. It was called Bifrost Bridge, and it was for young people. You go there with your guitar, and you sing songs. It was the folk song movement. So I brought my harmonica up there, and I play it completely seven universes out of tune with the actual song that was playing. I’d like to go back there and say “hi” to myself, and to everybody else.

When are you at your most creative?

I’m most creative between 4 and 5 a.m. Around 4:30 I get up and kick off my day. That’s when I can just touch a piece of paper, and it turns into a poem. It’s not like that, but I really feel very free. It’s like walking in the breeze, you know, just a breezy and little bit of a rainy feeling. And the color of the dawn is beautiful and quiet. And the trees are happy. That’s when I really like to write.

What keep you up at night?

My computerized fried burnt head keeps me up at night. I’ve been doing these virtual teaching classes. I’m co-teaching a group of students at Mary Baldwin University in Staunton, Virginia. I was just learning Canvas. You can make comments and announcements there, but I couldn’t even get in. Flipgrid—I didn’t know Flipgrid at all. They’re also on Flipgrid, which I couldn’t get into either. So all that fried me up. It’s fried onions in your ear.

What is your earliest childhood memory?

Probably my mom cradling me in her arms, singing me songs. That would be the super earliest one. And before that, I was a mariachi embryo.

We used to live on the outside of cities and towns because we were a farmworker family. We also lived on the side of highways. But they were small highways back then, and nearby the highways there’s an open zone that’s just dirt or shrubs, and sometimes it’s a little plateau-like area of dirt where, usually, big trucks park. But this was a little bit bigger than that. So a group of gentes started parking their trailers and trucks there. So that’s what we kind of settled in at one point.

I think in one of those moments, there was a well. I was hanging out around that well, just kicking stones around. I must have been 4 or 5 years old. And then I took off, to hang out by our trailer. But then people started asking: Where’s Juanito? Oh, he was over there by the well.

People started looking down the well to see if I’d fallen in. And then everybody started going “Juanito!”

I stayed behind the trailer, and I didn’t come out because it was kind of a dramatic moment. I even think my mom came out. So everyone went bananas because they thought I was way under there, and they didn’t see me. And then it was hard to go back into the scene because everybody’s been already traumatized, and so I didn’t want to go back into the scene. So I stayed behind the trailer until finally, I joined the scene.

Some of them were really relieved, and some of them were probably running after me with a broom. So that’s one of my earlier ones. It stays in my mind.

What do you do to decompress?

To decompress I take walks.

And in the backyard, I sweep around. I play with the dog—she’s a big dog, so she’s strong. She’s a Shepherd Lab. I call her “Panchi,” for Panchita, and my stepdaughter calls her Arya after “Game of Thrones.” So she’s Arya, that’s her elegant name, and her barrio name is Panchi.

I walk her. I do that midday-ish.

I also turn into the mummy. That’s how I decompress—I turn into a mummy. In Tijuana, they had or have a theater called Bujazan. One of the films that was really big in the early days was La Momia Azteca. The Aztec Mummy. Mummies are pretty tough already, but if it’s an Aztec mummy, then you really got it going. So I’d probably turn into an Aztec mummy. That’s what I do to decompress. I don’t really move that much. In the morning I’m Johnny Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah, and in the afternoon I’m the Aztec mummy.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

Kind of in an odd way I received it from Mr. Ezra Harrison Maxwell in high school. I decided in seventh grade the only way I’d ever be able to conquer my fear of speaking up, or raising my hand, or responding to the teacher’s questions was joining the choir. I didn’t want to, but that was the medicine I knew I had to take. By the time I was in 10th or 11th grade, it was still hard. And Mr. Ezra Harrison Maxwell said, you have a good voice, Juan, but you’re only using one-third of it.

That was a chill moment. After all these years of working on my voice, I still was only using one-third of it. So that was a wake-up Momia Azteca slap.

Before that, in third grade, the same thing happened. I didn’t know how to speak English super cool, and I got to school late. And no one—my mother, my father, none of us—knew about how registration worked. So my father opened the door of his truck and said, there’s the school.

I turned around, and there was a big, old building. And I thought, OK, there’s the school. That was it. They closed the truck door, and he zoomed away. And I walked across the street and opened the big, giant front door. And I looked straight ahead. It was an infinite hall. No one was out. The floors were waxed. It was dark brown. And all of the doors on the side were closed. You couldn’t hear a word.

So I just decided I’d open the first door on my right. I mean, what else are you going to do? I opened it and way down into the big, giant classroom there was a teacher with a little circle of students reading a book. So I was like Cantinflas and walked in and directed myself toward the teacher. And she decided to have me lean over her knee to be spanked. That was lesson one. And so from that day on I decided just to close down. I was gonna participate physically, but verbally, it wasn’t gonna happen.

And then, Mrs. Sampson called me up to sing in front of the class. But she was a very kind person, and she played a lot of music, gospel music, in the class. I was excited in that class, and I felt really groovy. So I went up, and she said, turn around and sing a song to the class. And I thought, I mean, come on. I’m a mummy. I don’t say anything. I don’t do nothing. This is not what I do. I don’t talk. I didn’t say that, but that was my reality. But she was sitting right next to me, very warm and kind. So I sang. I sang “Three Blind Mice.” And after I finished “Three Blind Mice,” she turned around to me and said, “You have a beautiful voice.”

I turned to her. I didn’t know what to do. It was such a big, magical thing she told me. And then I walked back to my back row seat. I just felt the electricity. I felt the magic, which became my life’s calling, to tell others the same thing, and to speak up. So that was a clincher. That was a key moment in my life. A big moment. And then, Mr. Ezra Harrison Maxwell: You’ve got a good voice, but you’re only using one-third of it.

So, it’s always been about my voice one way or another. It’s always been about that.

What is the last thing that inspired you?

The last thing that inspired me was the first thing. Which is life, you know? OK, let me get back down to the earth. One of my co-teachers, Adam Fajardo, started to put words up on a white screen for ideas to write poems. Just the words that were up there, that everybody was chipping in—you could type in from wherever you’re at, and they appear on the screen on a white page, inside the chat room thing. So they started to go up, they’re kind of appearing by themselves. That was very cool. I really liked that. Everybody was typing them in. You don’t know who’s typing them in, and they’re appearing in different colors. Words like “perception,” “reality,” and on and on. And they were kind of heavy, too; some pretty deep thinking. Edgy ones, like “rebirth” for example, and “reincarnation.” Seeing them all spread out in different colors, appearing before your eyes, that was nice.

This Zócalo event is about what poetry can offer us in distressing times. Is there a poetry reading that comes to mind that you would like to share in this moment?

I’m just finishing judging, with a number of other judges, the National Youth Program poetry program poets. They’re based in Washington, D.C. The ones that finally make it—I think there’s four or so—they travel throughout the United States together and read their poems at schools and different places. And every year, I’m telling you, the 15-, 16-, 17-year-old poets, they’re getting sharper, and deeper, and more experimental. And they’ve got some fabulous poems.

And one of the poets happens to be Latino, and he wrote a poem that if you read it from the first line to the bottom, it’s a kind of a—not right-wing, but a conservative-oriented statement on immigrants, immigration, and migration. And if you read it from the last line backward to the first line, it’s pro-immigrant and migrant. And it’s the same poem—no buttons, no levers, no windups. You read it from the first line down. No, we shouldn’t do this. It doesn’t have a raging tone, but it definitely has a bias. And if you read it from the bottom up to the top, it’s totally supportive. So how did he do that? It’s really well done.